Dr Charlotte Booth discusses new research from the National Core Studies Longitudinal Health and Wellbeing initiative on working from home and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The sudden lockdown in March 2020 caused a rapid shift from workplace to home-based working for many people. In this study, we used data from seven longitudinal studies to investigate whether home working was associated with poor mental and social wellbeing during the pandemic. Our findings can be used to inform current policy, as the trend for home working is prevailing in the post-pandemic era.

Why was the study carried out?

Working from home existed before the pandemic but was not the norm. At the start of the pandemic many people were forced to work from home, often for this first time in their lives. We used this opportunity to estimate the effect of home working on people’s mental health and wellbeing.

Many arguments can be made for the mental health benefits of working from home, as time otherwise spent commuting can be invested on interests outside of work or quality time with family. During the pandemic, people working from home were also more protected from risk of infection. However, working from home could be detrimental to mental health in some cases, such as when social connection or a sense of meaning in work is lost.

In our study, the pandemic context was important to consider as people’s mental health suffered generally during these times. However, we were able to control for participants mental health, wellbeing and work situation before the pandemic using existing longitudinal datasets, to better isolate the effect of working from home on mental health.

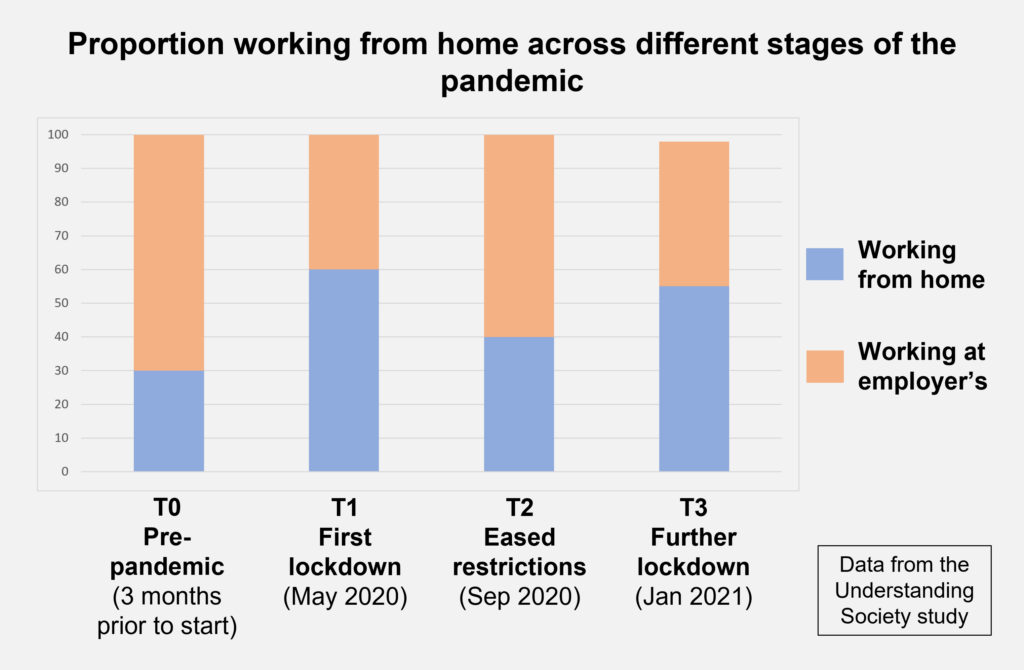

Restrictions and advice also changed a lot at different stages of the pandemic. In the first lockdown, everyone apart from keyworkers were forced to work from home. In the summer of 2020, restrictions eased, and people were encouraged to go back to work if they could adhere to social distancing. In the winter of 2020/21, restrictions were re-introduced, and people were again forced to work from home. The figure below shows the proportion of people working at home or at employer’s premises across these periods.

Which data and methods were used?

We used data from seven longitudinal studies that existed before the pandemic, so that we could include a large and representative sample of working aged people in the UK and consider people’s pre-pandemic work situation and mental health. This was important to be sure that our findings were accurate and not due to a sampling bias.

Each of the studies collected information about participants work life and mental and social wellbeing, including psychological distress, low life satisfaction, loneliness, low social contact, and poor self-rated health, across different stages of the pandemic:

T1: The first national lockdown (spring 2020).

T2: A period of eased restrictions (summer 2020).

T3: Another period of lockdown (winter 2021).

At each timepoint, we tested the association between work location – either at home or employer’s premises – and each of the mental and social wellbeing outcomes. A full range of confounding factors were considered, including work sector, key worker status, and propensity to work from home pre-pandemic.

We pooled results from each study using a “meta-analysis” to give an overall picture for the entire working population. Knowing that different sub-groups were likely to be affected to a varying extent, we also tested for any group differences by re-analysing data according to age (16-29; 30-45, 50+), gender (male, female), and education level (university degree, lower education).

What were the findings?

The main finding was that work location was not generally associated with mental or social wellbeing. Although at T3 (during the later lockdown), those working from home showed slightly higher risk for psychological distress compared to those working at employer’s premises. Our re-analyses showed that this effect was stronger in those with a lower level of education, who also reported increased loneliness at T3. This suggests that people with a lower level of education suffered more from home-based working in the later lockdown period.

Some further sub-group differences were found, as for those aged 16-29, working from home was associated with increased risk of loneliness and poor self-rated health at T1 (during the first lockdown). This suggests that the shock move to home working at the start of the pandemic may have increased loneliness and poor health in young people; a group who may have gotten more benefit from social connection in the workplace prior to the pandemic compared to older age groups.

Although in general, we found very little differences in mental and social wellbeing by work location. Of particular interest to current times, we found no significant differences at T2, during the period of eased restrictions. This suggests that outside of the pandemic context, when people have their general freedoms, their mental and social wellbeing will not be likely to suffer from home-based working.

What are the implications?

The shift to home working during the pandemic has had a lasting legacy. In the spring of 2022, when guidance to work from home was no longer in place, 38% of working adults continued to work from home at least some of the time. This figure rose to 61% in higher earners (earning over £40,000 per year).

Our research suggests that home working is not bad for mental health. Although, certain groups may be likely to suffer more from working exclusively at home, such as young people who may get more benefit from social interaction in the workplace.

Hybrid and flexible work arrangements are likely to be best for employee satisfaction and wellbeing, as depending on individual circumstances some people may prefer working mostly from home, while others may prefer more time in the office.

However, this hybrid model may be challenging for some organisations and will require adaptation from both workers and employers. Some journalistic evidence suggests that hybrid working has been particularly difficult for middle managers, as some have struggled to manage teams in different locations.

This is a very interesting topic that continues to change as we move into new phases post-pandemic. Future research should continue to monitor the mental and social wellbeing of employees across the multitude of work arrangements we see today, in order to find new ways to sustain and improve employee mental health.

The research presented in this blog post is based on the National Core study’s recent publication which can be viewed online.

About the author

Charlotte Booth is a Research Fellow at the UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies. Her research generally focuses on the development of mental health problems in children and young people.

She received her PhD from the University of Oxford in 2019.

Follow Charlotte on Twitter.

This blog post contributes to our ongoing work looking at Mental health in data.

I feel that working in both ways, whether from home or the office, is up to us to maintain our mental well-being. And yes, hybrid and flexible working could be the better option for a person, as you suggested. It gives us the freedom to choose the way we like to work. For related information, visit.

https://yourmentalhealthpal.com/work-from-home-and-mental-health/