Dr Patsy Irizar, Simon Fellow at the University of Manchester, discusses new data which shows how COVID-19 impacted the mental health of ethnic minority people.

Dr Patsy Irizar, Simon Fellow at the University of Manchester, discusses new data which shows how COVID-19 impacted the mental health of ethnic minority people.

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted ethnic minority people, in terms of both physical health (e.g., higher mortality rates, see Irizar et al., Sze et al. and Pan et al.) and economic (e.g., job loss) outcomes. I am interested in understanding whether ethnic minority people were also disproportionately impacted in terms of mental health outcomes. As part of my research fellowship, I am using data from the Evidence for Equality National Survey (EVENS), which is available from the UK Data Service, to explore ethnic differences in mental health during the pandemic, and the possible reasons for these differences.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic had a detrimental impact on mental health for many people in Britain, particularly during the first wave of infections and lockdown (e.g. Niedzwiedz et al., Pierce et al. 2020, Pierce et al. 2021). But some studies suggest that the long-term impact on mental health was minimal – though certain groups of people, including ethnic minority groups, reported worse mental health over time (e.g. Pierce et al. 2020). Existing studies are often limited as they do not have large enough samples of ethnic minority people, meaning groups are aggregated into broad categories and this may hide important differences in mental health across ethnic groups. This also means that they are not able to explore ethnic differences in mental health across other sub-groups, such as age and sex (and there are known differences in mental health depending on age and sex).

Novel data from the Evidence for Equality National Survey (EVENS)

EVENS is the largest cross-sectional survey of ethnic minority people in Britain, recruiting large samples of people from 18 ethnic minority groups, including those who tend to be under-represented in surveys (e.g., Gypsy and Roma people). This means that researchers have enough statistical power to conduct novel analyses and look at differences across ethnic groups, as well as other sub-groups, such as sex and age groups. EVENS includes weights that account for differences between the sample and the British population. By applying these weights, the data can be used in ways that can be said to be representative of the British population.

Identifying ethnic inequalities in mental health

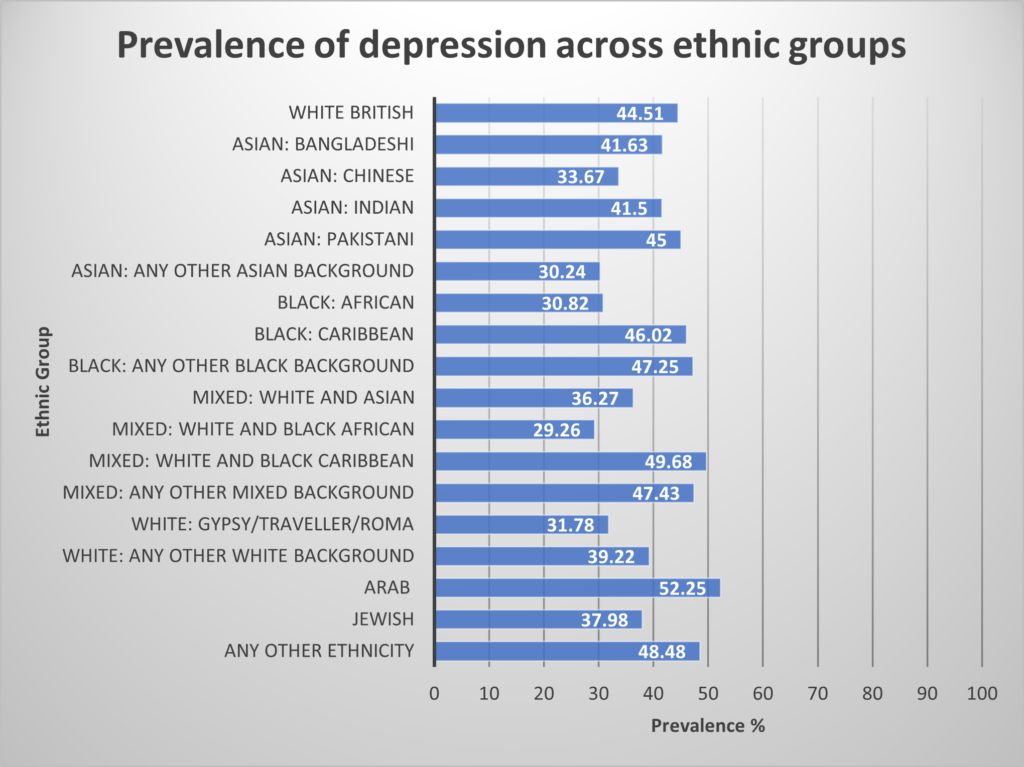

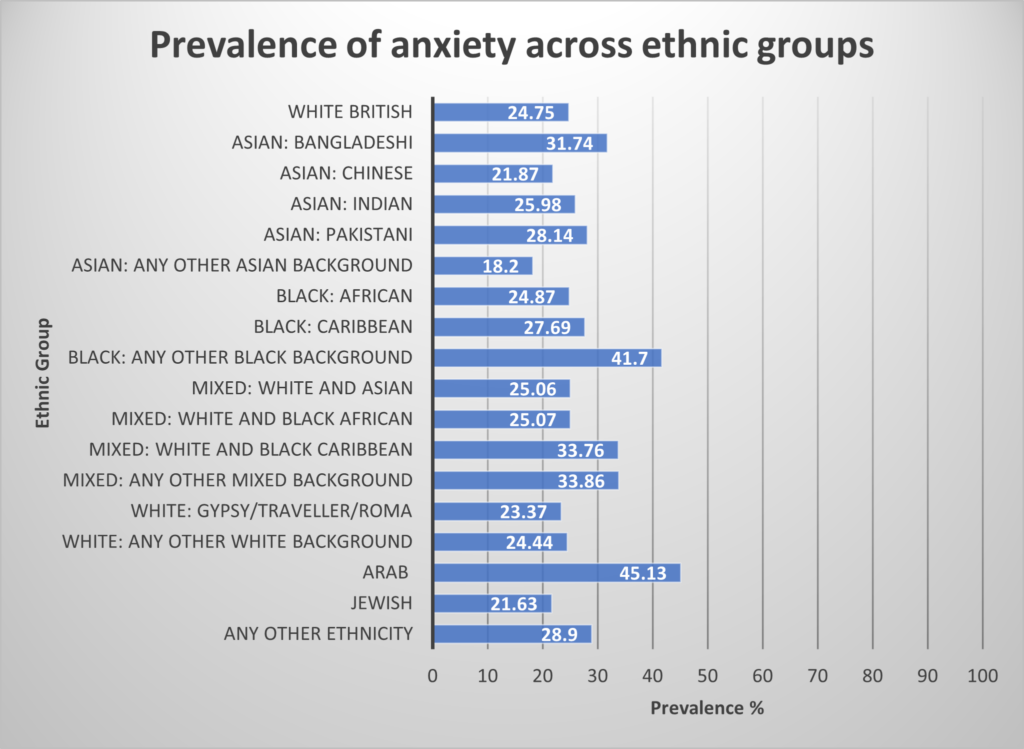

My research examined ethnic differences in depression and anxiety, during the COVID-19 pandemic. This analysis included over 12,000 participants from 18 ethnic groups, aged between 18 and 60 years old, who completed the EVENS survey between February and November 2021. Depression was self-reported by participants, through 8 questions which asked about feelings of sadness and loneliness. Anxiety was also self-reported, through 7 questions which asked about feelings of worry, nervousness, irritability, and fear. I investigated whether people from ethnic minority groups were more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than White British people, and whether any differences were consistent for men and women and across age groups. I also explored whether ethnic differences in mental health persisted if levels of previous infection, bereavement, and existing clinical diagnosis of depression/anxiety were the same across groups (if not, then these may be important explanatory factors).

Evidence of ethnic inequalities in mental health

Across the whole sample, including White British people, 44% met criteria for depression and 26% for anxiety. Concerningly, Arab people were 2.5 times more likely to report anxiety than White British people, and people identifying as any other Black background were twice as likely to report anxiety. People identifying as Mixed White and Black Caribbean and any other Mixed background were 1.5 times more likely to report anxiety, but this lessened after controlling for ethnic differences in previous infection, bereavement, existing clinical diagnoses, so these factors may be important explanatory factors for these ethnic groups. The analysis also showed lower levels of depression for people identifying as Black African, and any other Asian background.

See this page for an accessible table version of this figure

Overall, women were more likely to report depression and anxiety than men, and younger people were more likely to suffer from poor mental health than older people, but these findings were not consistent across ethnic groups. Arab men and women showed similar levels of anxiety (higher than White British men and women). Older Arab people were more likely to suffer from depression and anxiety, whereas younger Arab people were less likely, compared to White British people of the same age. The same pattern was found for Mixed White and Black Caribbean people, but only for anxiety.

See this page for an accessible table version of this figure

These findings have identified certain ethnic minority groups who may require more targeted mental health support to ensure an equitable recovery from the pandemic, particularly Arab people, with almost one in two Arab people meeting criteria for depression and anxiety. This is concerning as research suggests that Arab people are less likely to seek psychological help than White British people, and face barriers to healthcare services, such as discrimination. Though some ethnic groups showed lower levels of depression compared to White British people, there were ceiling effects across the whole sample (over a quarter of people within each ethnic group met criteria for depression), which may be because symptoms of depression occur following loss and everyone, regardless of ethnicity, was at risk of loss during the pandemic. I theorise that the higher levels of anxiety among certain ethnic groups may be because symptoms of anxiety follow threat and danger, and these experiences (e.g., fear of becoming infected and dying with COVID-19 or losing income) may have been greater for ethnic minority groups.

Following on from this analysis, my fellowship research next aims to determine the reasons for depression and anxiety among ethnic minority people in the UK, with a focus on the ways in which experiences of racial discrimination over the life course contribute directly to poor mental health, as well as indirectly, by influencing factors such as greater levels of COVID-19 infection and financial insecurity.

Further information

The full article, The prevalence of common mental disorders across 18 ethnic groups in Britain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence for Equality National Survey (EVENS), is available open-access in Journal for Affective Disorders. This work was conducted by Patricia Irizar, Harry Taylor, Dharmi Kapadia, Matthias Pierce, Laia Bécares, Laura Goodwin, Vittal Katikireddi, and James Nazroo.

Professor Nissa Finney, EVENS project leader, gave a presentation about EVENS as part of our Poverty in Data event. You can view the video here or on our YouTube channel.

About the author

Dr Patsy Irizar is a Simon Research Fellow at the University of Manchester. Her research focuses on understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of ethnic minority people, centred around the roles of structural and institutional racism and racial discrimination. Patsy is a mixed methods researcher, using large secondary quantitative data sources as well as in-depth primary qualitative data to understand the social determinants of health inequalities.