In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

Welcome to the final part of this mini series on the ease and ethics of utilising Twitter data, based on a talk I gave at the NCRM Research Methods e-Festival.

In my last post, I discussed who is responsible for tackling the ethical issues surrounding Twitter data use. In this final post, I’ll be considering whether we should be using Twitter data at all, and what steps we can take next.

Photo by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash

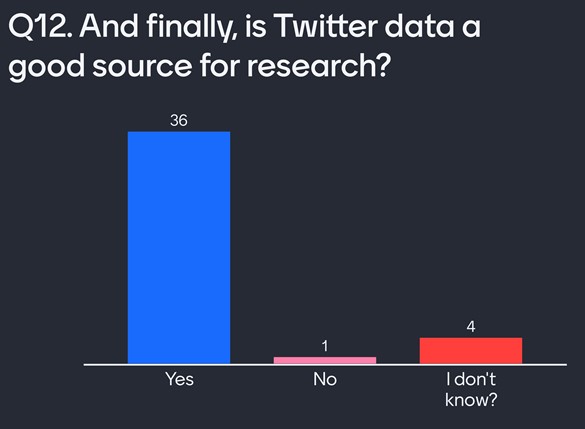

Q12: Is Twitter a good source of data for research?

Ask yourselves if Twitter is a good source of data for impactful research. I asked my audience the same question, and the majority felt that is was, as you can see in the Mentimeter responses below.

Needless to say, there are a lot of things to think about here. Twitter data is a vast and rich source of data, but there are also limitations and bias that we need to consider: different platforms are aimed at different demographics; individuals who do not use social media or the internet are not represented; Twitter users are on average American, 25–34-year-old males; and so on. Where Twitter data is being used in research to inform policy, we need to make these sorts of limitations clear and take steps to reduce bias in our sampling.

Mentimeter responses to Q12

Q13: Should we be able to use Twitter data in research?

To get my audience thinking about this question, I prompted them with two different points of view.

We should be able to use Twitter data

One argument here is that Twitter data is public, so the question of whether we should be able to use it is itself redundant. Arguably, the purpose of any social media platform is to give user content some exposure. Users who post insensitive content should “know better”, and if they don’t want to get in trouble for posting inappropriate content they simply shouldn’t do it.

All social media data is valuable and offers any user a wealth of insights into, say, the public perception of personal comments, a political party, a share price, and beyond. Why should we ignore such a powerful dataset over what some see as a small privacy concern?

In short, this is public data, so we can ignore GDPR, future data legislation, and morals.

We shouldn’t be able to use Twitter data

Not all users want their content to be observed at scale or even realise they are opening themselves to the potential misuse of their personal data. Consider the following:

- Do children understand how their data will be used?

- Do adults understand how their data will be used?

- Did all users anticipate that machine learning would enable insights from their data?

- Did all users anticipate this could lead to targeted advertisements and political manipulation?

- Are all users confident that we won’t find more powerful ways to misuse this data?

- Do all users feel their historic tweets do not contain dated views?

Many users anticipate their followers seeing their content. Some users would be embarrassed if somebody outside of their preferred network saw their content. Not all users are fully aware of the extent their data can be used by third parties.

In any academic study, we have to abide by GDPR and obtain consent to use personal data. However, as I’ve explored in my previous posts, if we were to try and reach out to Twitter users to inform them that their data is being used, many would become uncomfortable. The context the tweet is taken in (or out of!), the purpose of scraping the data, and the organisation using it affect the scale of this discomfort. So there’s a tension here.

That’s made worse by the fact that Twitter content can become indexed and searchable through Google, meaning that the risk of reidentification from free text is high. In any academic study we work hard to minimise the risk of reidentification of our participants, but what should we do when it comes to Twitter users, given the tension I outline above? Again, we could justify potential reidentification by claiming that Twitter data is public. But is it possible that public and observed data are two very different things?

In any academic study, we would give all users the ability to revoke their data at any point. We don’t offer this option when the data source is social media. As I’ve shown in previous posts, if we were to offer Twitter users this option they’d again feel uncomfortable in being approached by someone they might not have realised would be able to see, and use, their tweets. And from the researcher’s perspective, removing thousands of revoked data points every month would be anything but trivial. So how could we give users the right to withdraw without upsetting them or creating unmanageable workloads? Who is ultimately responsible for handling this challenge? Is it simply easier and more ethical to say we shouldn’t be allowed to use Twitter data in this way?

Conclusion

At this point in time, the University of Manchester, where I’m based, has released over 500 published works that use Twitter data. Are we already too late to change the problematic way in which this data is used?

Some universities are starting to change their ethical review processes to provide greater protection where research is using social media data. At the University of Warwick, for example, a review of ethical procedures led to a new requirement that all research projects using social media data undergo ethical review.

However, similar ethical review processes are not yet evident at all universities or outside of academia, meaning users remain vulnerable to the potential misuse of their data. We therefore need a wider solution that takes into account the following:

- Informed consent – users have no idea how often their content is scraped, or to what ends it is used. Being approached for consent by the data scrapers leads to discontent. Twitter itself is in the best position to solve this problem (see yesterday’s post for more on this).

- Anonymity – any user can scrape names, locations, and other protected features linked to tweets. A user can then reidentify a tweet by Googling the content of that tweet. One solution could be to provide statistical disclosure control of text data to protect anonymity.

- Right to withdraw – as users aren’t informed, they have no idea they need to withdraw from anything. If they could withdraw, how would researchers manage this after scraping millions of users? Twitter again is in position to help solve this.

- Ethical review – Universities should step up and accept that social media data requires some form of protection. Mandating ethical reviews for any research project using social media data is the first step forwards in this process. Similar processes could be adopted in industry.

That wraps up my exploration of the complex topic that is Twitter data and ethics. Whilst we don’t yet have answers to all of the questions I’ve raised, it’s important that we take action for ensuring responsible use of social media data.

If you missed the previous posts in this series, you can catch up below:

- Part 1 : Should we use Twitter data in academia?

- Part 2: Should industry have access to Twitter data?

- Part 3 : Is using Twitter data ethical?

- Part 4 : Who is responsible for Twitter data?

- Part 5 : What is next for Twitter data?

All data used in these blog posts are available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

About the author

Joseph Allen is a Research Associate at the UK Data Service, based at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at the University of Manchester. For the last year Joe has been focusing on making Twitter easier to use, whilst also exploring the ethics of this access.

Feel free to contact Joe at Joseph.allen@manchester.ac.uk or on Twitter @JosephAllen1234.

Featured image by Joshua Hoehne on Unsplash