In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data. We’ll be publishing one post each day this week, so follow along from now until Friday!

In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data. We’ll be publishing one post each day this week, so follow along from now until Friday!

I recently had the pleasure of speaking about Twitter at the NCRM Research Methods e-Festival. In my talk, I focused on the ease and ethics of utilising Twitter data in academic research. In this five-part blog series, I introduce some of the questions I asked the 42 attendees, and my interpretations. A full recording of this talk is available on the UK Data Service YouTube channel.

Photo by Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash

As the attendees were all academics and were aware of the ethical use of data, you can expect some bias in these results. Data was collected via Mentimeter – a useful interactive tool that allows instant responses from audience members. All data used in this blog post is available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

To begin, I introduced the following “socially good” scenario to my audience, and posed a series of questions for them to respond to.

Scenario 1: “The University of Manchester is doing a study on how hate speech relates to veganism and plant-based diets. Your tweets about food and veganism have been scraped.”

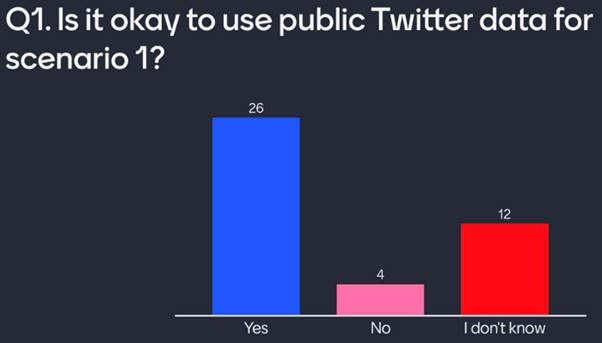

Q1: Is it okay for Twitter data to be used in this way?

Most attendees believe that they aren’t tweeting anything controversial here. Society incentivises individuals to “donate” their data in these scenarios. We are already viewing our data as transactional but expect no financial compensation.

Many would offer this data when asked. Refusing to share your data here may suggest that you have something to hide. Do you believe your opinions on veganism are controversial? Would you change your answer if you did, or didn’t?

We can see in the Mentimeter responses below that many users consider this an acceptable use of Twitter data. Some are unsure, and few reject this idea.

Mentimeter responses to Q1

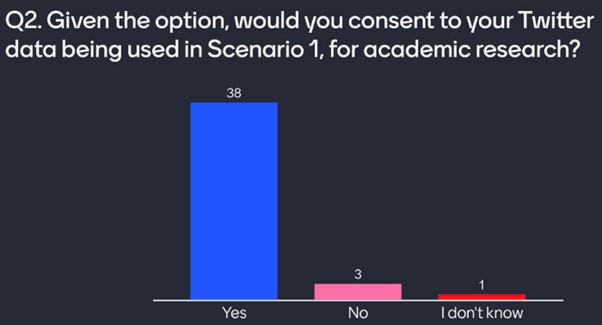

Q2: Given the option, would you consent to your Twitter data being used in Scenario 1?

Twitter data is public. We have limited control of our data once a tweet is made. Deletion won’t remove data already scraped. With this question, I wanted to offer a hypothetical scenario where users had a choice in giving consent. In any interview style study, this consent would be the default. Most users approve of the “donation” of their data in this case.

Mentimeter responses to Q2

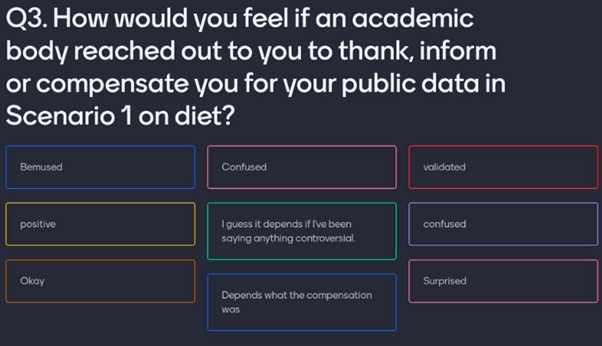

Q3: How would you feel if an academic body reached out to you to thank, inform, or compensate you for your public data in Scenario 1?

Here we observe a phenomenon. When organisations scrape data, we assume the users are all well-aware that their data is available for use, and may well be used, in this way. To put it pessimistically, we assume our users give informed consent simply through using Twitter in the first place – consent that they cannot retract once putting a tweet out into the world.

However, when asked how they would feel if researchers were to contact them to seek true consent, responses from the majority of attendees suggest that being approached would make them uncomfortable. As seen in the Mentimeter responses below, some attendees “would not want to be contacted” and most attendees would feel confused by this contact.

Mentimeter responses to Q3

One attendee points out that their answer would change based on whether they felt they had tweeted anything “controversial” on the research topic. Imagine the bias introduced to research if we only collected data that was considered “not controversial”.

When using Twitter, most users are not intending to be featured in a news article, quoted in an academic study, or monetised by a large business. But by tweeting, users are opening themselves up to their tweets being used in precisely this way.

Conclusion

In this socially good example, it’s quite easy for me to be pessimistic. Users are willing to donate data, but only based on the context of the research question.

Are we confident that this data will always be taken within context? Will each tweet forever remain on the correct side of history?

This is just the first part of a five-part series on the ethics surrounding the use of Twitter data. In the next part I will introduce an example of malicious Twitter data use, and we will observe how the audience’s views on data donation are flipped on their head.

Check out the whole series as it becomes available below:

- Part 1 : Should we use Twitter data in academia?

- Part 2: Should industry have access to Twitter data?

- Part 3 : Is using Twitter data ethical?

- Part 4 : Who is responsible for Twitter data?

- Part 5 : What is next for Twitter data?

All data used in these blog posts are available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

About the author

Joseph Allen is a Research Associate at the UK Data Service, based at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at the University of Manchester. For the last year Joe has been focusing on making Twitter easier to use, whilst also exploring the ethics of this access.

Feel free to contact Joe at Joseph.allen@manchester.ac.uk or on Twitter @JosephAllen1234.

Featured image by Brett Jordan on Unsplash