In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

This is part four of a five-part series on the ease and ethics of utilising Twitter data, based on a talk I gave at the NCRM Research Methods e-Festival. Today I’m also guest blogging over on the University of Manchester’s Research IT blog, as their post on ‘Analysing Tweets from Twitter’ partly inspired this mini series, so make sure you check out the Research IT blog as well!

In the last post, I discussed the ethical review process for academic research, and how that might help bridge some of the gaps in responsibility in current processes relating to the ethical use of social media data. In this post, I’ll be reflecting on who should hold responsibility for overseeing and ensuring the ethical use of Twitter data.

Photo by Alexander Shatov on Unsplash

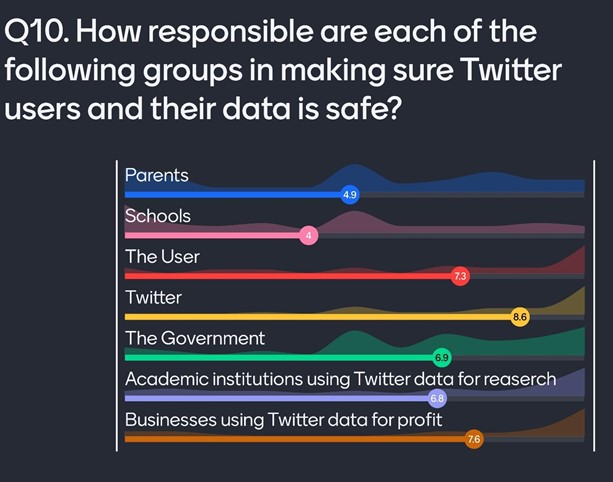

Q10: How responsible are each of the following groups in making sure Twitter users and their data is safe?

In asking my audience this question, I wanted to find out how much responsibility certain groups were seen as having when it came to protecting their Twitter data:

- Parents

- Schools

- The User

- The Government

- Academic Institutions

- Industry

One response might be that parents and schools are responsible for raising the next generation of social media users, and are therefore responsible for encouraging safe use of online data. Digital hygiene is part of the curriculum at many schools in the UK, despite many adults not understanding the importance of it.

Another response could be that the government should intervene when businesses use data in an unethical manner. While both these scenarios could offer practical solutions to some of the problems I’ve explored in this blog series, I wanted to find out if my audience offered up similar views or whether they felt responsibility lies elsewhere.

I gave each attendee the option to rate each group from “not responsible” to “largely responsible” on a scale of 1 to 10. You can see their responses in the graph below.

Mentimeter responses to Q10

I’ve run this survey a number of times with different audiences and what I’ve found each time is that attendees in general feel Twitter is responsible for protecting personal data. I agree. Twitter is in the unique position of being able to trace the collection of their data through their API. They can ask who is collecting data, why that data is being collected, and can approve or reject an application.

Twitter is best equipped to give users the option of providing informed consent and the right to be forgotten.

To my joy, attendees felt that parents and schools had the least responsibility, with many feeling they had zero responsibility. The average Twitter user is 25 or above, so parents and schools surely have little sway in protecting the current demographic of users. This is not to deny that we all hold a degree of responsibility for helping prepare the next generation of users to have a healthier relationship with social media, but I don’t think parents and schools are ultimately responsible for ensuring the safety of personal data, and of course we cannot understand the risks that may be faced online in the future.

As the Mentimeter responses show, my audience placed a lot of emphasis on the user being responsible for their own data. I pessimistically call this the “you should know better” argument. Our expectation that the average user understands data misuse is far too high; many Twitter users will not stop to consider what might happen to their data and will not always realise that they are tweeting something that could be taken as controversial. Users generally don’t read or understand the terms of service for each platform they use.

In my view, the methods that social media platforms employ to educate their users simply do not work.

When it came to the government, my audience had a wide range of opinions. The government can legislate and enforce protection for Twitter users. However, current legislation on data protection is inadequate and often slow to come into force. In some sense, we need the problematic consequences of unprotected data use to arise to create urgency for government action.

My audience voted for businesses as the second group most responsible for protecting personal Twitter data. But there are conflicts of interest to consider here. Businesses making use of Twitter data can fund Twitter’s development of a better API, so there’s an incentive to share the data, but businesses generally want the best data they can get for the cheapest price. No doubt there are some progressive business employees questioning the ethics of the data they use, but sadly for the majority ethics is secondary to profit.

As I suggested in my previous post, there is a real opportunity to encourage better use of Twitter data in academia.

For me, a quick win would be to introduce to all universities the requirement of an ethical review for any project using social media data. Doing so would kickstart the process of protecting social media data, the way we would any other personal data.

Twitter could learn from these processes and update their offering to academics with opportunities for providing informed consent and project-level justifications for scraping. Whilst there are signs of positive developments within academia, there is still some way to go in best practice being adopted elsewhere. Personally, I fear that Twitter might simply be willing to rely on the assumption that users happily “donate” their data, thus facilitating third party misuse and leaving users vulnerable to having their personal data to used in a way that’s beyond their control.

Conclusion

Overall, responses from my audience indicate that Twitter itself is seen to have the most responsibility for tackling the ethical problems of Twitter data use. In theory, they have the power to enable informed consent and grant users the right to withdraw from studies, where nobody else can. However, if and when this sort of governance will come into practice, remains a matter of much debate.

In the next, and final, part of this blog series, I will wrap up my discussion by considering what must come next for users of Twitter data.

Thank you to Research IT for having me as a guest blogger for this post. You can find out more about their activities on the Research IT website.

Check out the whole series as it becomes available below:

- Part 1 : Should we use Twitter data in academia?

- Part 2: Should industry have access to Twitter data?

- Part 3 : Is using Twitter data ethical?

- Part 4 : Who is responsible for Twitter data?

- Part 5 : What is next for Twitter data?

All data used in these blog posts are available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

This blog is being published in conjunction with the University of Manchester’s Research IT blog.

About the author

Joseph Allen is a Research Associate at the UK Data Service, based at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at the University of Manchester. For the last year Joe has been focusing on making Twitter easier to use, whilst also exploring the ethics of this access.

Feel free to contact Joe at Joseph.allen@manchester.ac.uk or on Twitter @JosephAllen1234.

Featured image by Alexander Shatov on Unsplash