Josh Cottell and Elizabeth Simon present findings from a recent report looking into the what influences Londoner’s wellbeing, and what can help.

In a recent report co-authored by the Mile End Institute at Queen Mary University of London and Centre for London, we explored levels of wellbeing among Londoners, comparing wellbeing outcomes in the capital to those experienced in other parts of the UK and identifying the key factors that shape wellbeing in the capital. Contrary to some previous studies, our research finds that Londoners do not have particularly poor wellbeing outcomes. In fact, they have fairly average levels of wellbeing compared to those living in other parts of the UK. Additionally, we find that for Londoners, it is how satisfied they are with their leisure time that has the strongest influence on their wellbeing, on average. Of course, the picture is more complicated than this, and public policies seeking to improve wellbeing in the capital and beyond should reflect these nuances.

Do people living in London have worse wellbeing outcomes?

A handful of recent studies have shown that Londoners have some of the lowest levels of wellbeing and some of the poorest mental health outcomes in the UK, on average. This begs the question, is there something specific about living in London that worsens our wellbeing?

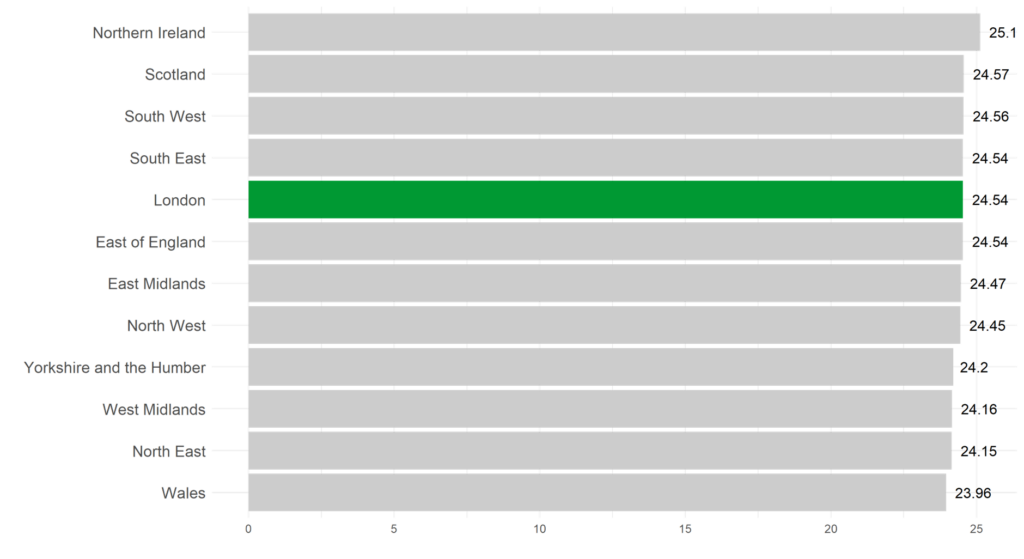

Our recent work suggests not. In fact, it suggests that Londoners have fairly average levels of wellbeing when compared to those living elsewhere in the UK. Figure 1 shows the average wellbeing scores of Understanding Society respondents residing in each UK region in 2018-2020. This shows that while Londoners are far from having the best wellbeing outcomes, they are also far from having the worst.

Figure 1 – Average Wellbeing Scores across UK Regions

We also tracked the wellbeing of Understanding Society respondents over time – using data from 2009 to 2020 – to explore whether respondents who moved in to, and out of, London experienced substantial changes in their wellbeing scores which coincided with these moves. We found that people’s wellbeing decreased after both kinds of move, on average. This is not the pattern we would expect if there was something specific about living in London that worsened wellbeing outcomes. If this was the case, we should see individuals’ wellbeing declining after they move into London and improving when they move out of the capital. Our findings suggest it is the experience of relocating itself that has a negative impact on wellbeing, rather than the experience of living, or not living, in London.

What are the key determinants of Londoners’ wellbeing?

Existing research has shown that a wide range of inter-linked environmental, social, political, behavioural and demographic factors shape our wellbeing outcomes, but which factors are the key determinants of Londoners’ wellbeing?

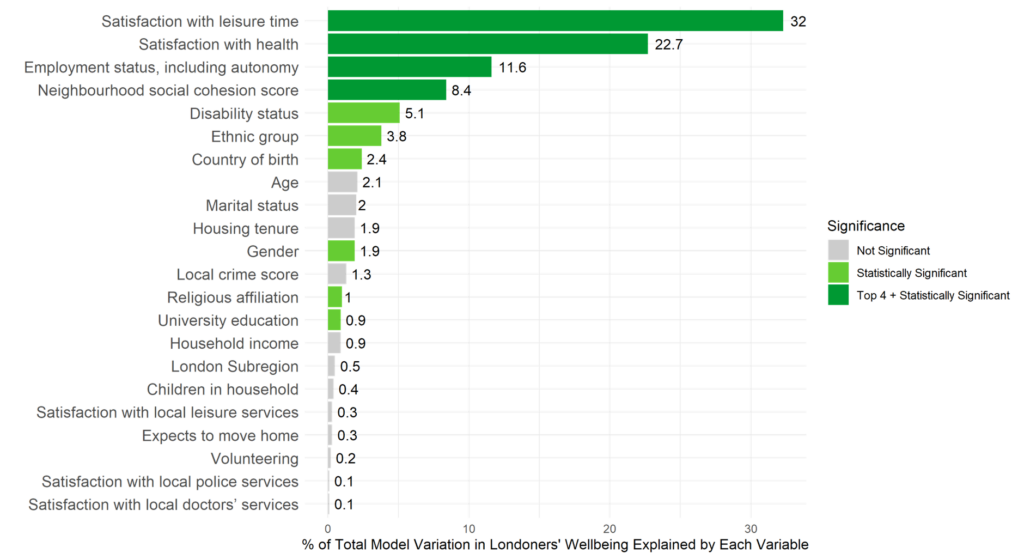

We explored this question by analysing the most recently collected Understanding Society data on wellbeing (2018-2020) using a multiple regression analysis. Using this statistical technique allowed us to identify the independent association of each factor with individuals’ reported wellbeing scores, after accounting for the influences of all other factors. Our regression model showed a plethora of factors had statistically significant effects on Londoners’ wellbeing; that is, effects which were so strong that they could not be explained by chance alone. These are highlighted in green in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Relative Contribution of Each Factor to Explaining Londoners’ Wellbeing

Four of these factors had particularly strong influences on Londoners’ wellbeing which we discuss below (see the dark green highlight in Figure 2). Taken together, these factors were able to account for almost 75% of the total variation in wellbeing outcomes explained by our regression model. Many other things matter, but our evidence suggests that these are particularly strong determinants of Londoners’ wellbeing which we believe must be considered when thinking about how we can design and enact policies that will improve outcomes across the city.

Employment status, workplace autonomy and wellbeing in London

Londoners who are employed in jobs with high levels of workplace autonomy have significantly better wellbeing outcomes than those who are employed in jobs with low levels of workplace autonomy and those who are in the ‘other’ employment category (not in employment but not retired).

Satisfaction with leisure time and wellbeing in London

Those who are satisfied with their leisure time tend to exhibit higher levels of wellbeing than those who are not, but this pattern does not hold true for everyone. We find no evidence that Londoners who are employed in jobs with low levels of workplace autonomy will have better wellbeing outcomes if they are satisfied with their leisure time, as we do for those with all other kinds of employment statuses.

Satisfaction with health and wellbeing in London

Londoners who are satisfied with their health have wellbeing scores which are considerably higher than those who are not satisfied with the health, on average. Much of this effect is driven by Londoners who report experiencing a long-standing physical or mental impairment, illness or disability, and younger Londoners, for whom this association is particularly strong.

Our findings clearly indicate that dissatisfaction with health has a much more negative effect on wellbeing outcomes for Londoners with disabilities, and younger Londoners, than it does for Londoners who do not report having any kind of long-standing physical or mental impairment, illness or disability, or for older Londoners.

Neighbourhood social cohesion and wellbeing in London

Neighbourhood social cohesion has a ‘protective effect’ on Londoners wellbeing; those living in areas they perceive to be cohesive have wellbeing scores which are much higher than those living in areas where they perceive there to be low levels of cohesion, on average. This protective effect is especially strong for those with higher household incomes.

How do we improve wellbeing in the capital?

Now we know what aspects of Londoners’ lives are having the biggest impact on their wellbeing, we can explore what steps governments, employers, and others can take to improve wellbeing, especially for those currently experiencing the worst outcomes.

We think wellbeing should play a more central role in policy making. Decision makers could, for example, be required to consider how their policies will influence people’s wellbeing, as has been introduced already in Wales via the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act.

There are a range of actions we recommend that policy makers take to boost wellbeing. Some, like actions that would support people facing high rents and overcrowded housing, would have positive effects in a range of the areas identified in our research. In this example, enabling more people to afford access to a decent home would support Londoners’ health, reduce unhealthy stress, and enable more people to enjoy their leisure time by ensuring they have somewhere that is comfortable, safe and secure to live. Knock-on effects could enable more people to access secure, well-paid work. Other policy changes we have identified are more closely focused on making improvements across one of the specific factors that our research identified as most closely linked to Londoners’ wellbeing.

To improve people’s sense of workplace autonomy and satisfaction with their leisure time, public policy should start with those who often lack control over both: shift workers. National government should legislate to ensure shift workers have adequate notice for shifts, so they are better able to plan their finances, childcare and leisure activities.

Many people in London and across the UK experience chronic poor health or have a disability. This fact shouldn’t determine the degree to which such people are able to get around their local area, access services, or otherwise participate in society. Service providers across the public and private sectors should use the social model of disability when designing services, adjusting their delivery so that people with different needs can participate fully.

To boost social cohesion in London’s neighbourhoods, local authorities should ensure new and redeveloped neighbourhoods include spaces where people can relax and connect, including benches on high streets, and parks and green spaces which suit local people’s needs. These spaces would also encourage and enable people to be more active in their area, supporting Londoners’ health. Government should also reverse cuts in the funding for local authorities to deliver services that bring people in a neighbourhood together, such as older people’s day centres and children’s centres.

Despite the challenges facing governments in recent years, there has been progress in a number of these areas and we have seen more of a focus on wellbeing from parts of national, regional, and local government. However, we must do more to boost wellbeing in the capital and across the UK, more widely. We hope the evidence our report provides gives a useful steer on where policy makers should focus their efforts in the years to come.

To learn more about our findings and recommendations, please take a look at the full report here. This work was co-authored with Zarin Mahmud, Claire Harding and Professor Patrick Diamond.

About the authors

Josh Cottell is Head of Research at Centre for London. Since joining the Centre in 2021, he has published research on London’s housing crisis, inequality within the capital, and how to improve Londoners’ wellbeing. Before joining Centre for London, Josh worked at the Education Policy Institute.

Dr Elizabeth Simon is a Postdoctoral Researcher in British Politics, based in the Mile End Institute and QMUL’s School of Politics and International Relations. Her research interests extend broadly across the topics of attitudinal formation, political behaviour, inequalities and identities and working on public policy projects.