This week is Carers week, an annual campaign to raise awareness, highlight challenges and celebrate unpaid carers. Unpaid carers play a critical role in our health and social care system and even more so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anne Alarilla (one of our Data Impact Fellows), Fiona Grimm and Mai Stafford explore who was providing care during the second wave of the pandemic and why this is important.

Why does this matter?

The response to COVID-19 has strengthened the UK’s sense of community and willingness to provide support and care for others. At the same time, the reduction and closure of social care services, such as support services and day care, and rising care needs have fuelled even greater need for unpaid care. In a survey conducted by Carers UK in September 2020, eight out of 10 carers were providing more care since the start of the pandemic. This increase in care burden may also have affected their own health and wellbeing. During October/November 2020, local authorities reported an increase in requests for support due to carer breakdown, sickness, or unavailability.

It has been estimated that unpaid carers have saved the UK £530 million of care costs per day during the pandemic. Yet, throughout the pandemic, government support for unpaid carers was limited and often introduced late.

Why did we look into it?

At the Health Foundation, we use data and analytics to tackle major challenges within health and care. Our previous work highlighted the significant impact of the pandemic on care workers and on people receiving formal care, based on novel analysis of public and patient-level data. But there are gaps in the available data that prevented us from getting a complete picture of the impact on the wider social care sector. We therefore explored other data sources that might help us to better understand the impact on people providing unpaid care during the pandemic. The use of survey data allowed us to capture individuals who may not be in contact with services and not represented in routine data.

This blog post presents the findings from a descriptive analysis of the latest waves of the Understanding Society COVID-19 survey (November 2020 and January 2021), building on analyses of earlier waves done by Carers UK and others (Gallagher et al, Xue et al).

Identifying unpaid carers in survey data

The UK Household Longitudinal study (Understanding Society) is a study that collects data on social and economic changes in the UK population. Separate from the main survey, Understanding Society has a special COVID-19 survey to explore the impact of the pandemic.

For our analysis, we combined Wave 6 (November 2020) and Wave 7 (January 2021) of the COVID-19 survey. For individuals who participated in both waves, we only used Wave 7. Unpaid carers during the second wave of the pandemic were defined as respondents who answered yes to at least one of the following questions in November 2020 and/or January 2021:

- Is there anyone living with you who is sick, disabled or elderly whom you look after or give special help to (for example, a sick, disabled or elderly relative, husband, wife or friend etc)?

- Thinking about the last 4 weeks, did you provide help or support to family, friends or neighbours who do not live in the same house/flat as you?

To compare changes pre pandemic, we used Wave 10 of the Understanding Society main survey (2018/2020). Unpaid carers pre pandemic were defined as respondents who answered yes to at least one of the following questions during 2018/2019:

- Do you provide regular service or help for any sick, disabled or elderly person not living with you?

- Is there anyone living with you who is sick, disabled, or elderly, who you give special help to?

There were some differences in the definition of unpaid caring before and during the second wave of the pandemic, which may influence the changes we observed. Even so, it is currently the best available approximation. The code for our analysis can be found on GitHub.

What did we find?

Many people started to provide care during the pandemic

We found that two thirds of the individuals providing care during the second wave of the pandemic were not previously providing any care (67%). This confirms previous findings from Carers UK that suggested there have been 4.5 million new carers since the start of the pandemic.

Our analysis showed that almost half of carers providing 20+ hours of care per week during the second wave of the pandemic were not previously providing care (45%). This might represent a considerable change in responsibilities for some people, particularly during an already difficult time. It is important that these new carers are aware of and are able to access available support.

The change in the definition of caring outside the household between wave 10 of the main survey and the COVID-19 survey may be contributing to this increase in the number of unpaid carers we observed. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to only include those providing care within the same household during the second wave of the pandemic. We found that around one in three individuals providing care (within the same household) during the second wave of the pandemic were not previously providing any care (33%). We also found that around one in five carers providing 20+ hours of care (within the same household) per week during the second wave of the pandemic were not previously providing any care (20%).

Figure 1: Changes in the proportion of people providing unpaid care during the pandemic

View the data or click image for larger version.

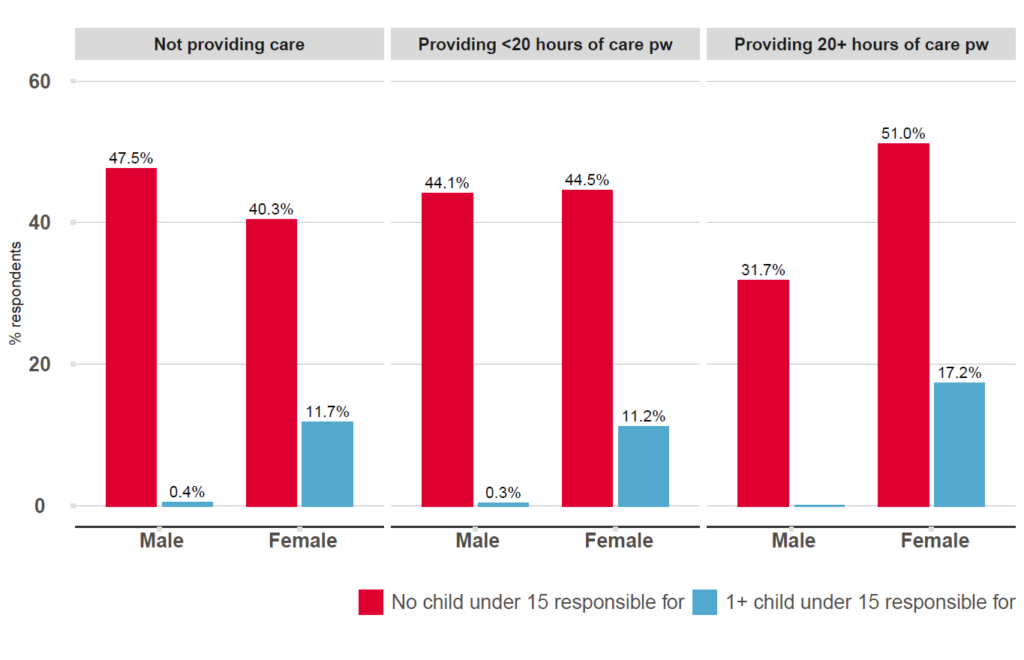

Women were more likely to be providing unpaid care and childcare during the pandemic

Early in the pandemic (April 2020/ May 2020), women were more likely to provide care and spend more hours on housework and childcare (Gallagher et al, Xue et al). We found that this pattern continued during the second wave of the pandemic.

Compared to men, women were more likely to provide care and were more likely to provide more hours of care. One in three women were providing some form of care (35%) and women accounted for 68% of those providing 20+ hours of care per week (Figure 2).

Women were also more likely to be responsible for both unpaid caring and childcare. One in four women providing 20+ hours of care per week were also responsible for at least one child under 15 years (26%).

These findings suggest that the pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on women’s caring responsibilities and additional support on how they can manage unpaid care alongside their other household and work responsibilities should be provided. Combining unpaid caring and paid employment can be difficult. With women being more likely to be in uncertain employment and more likely to have been furloughed during the pandemic, it is important that inequalities are not exacerbated through lack of support for unpaid carers.

Figure 2: Gender and childcare responsibility by caring status during the second wave of the pandemic

Accessible version or click image for larger version.

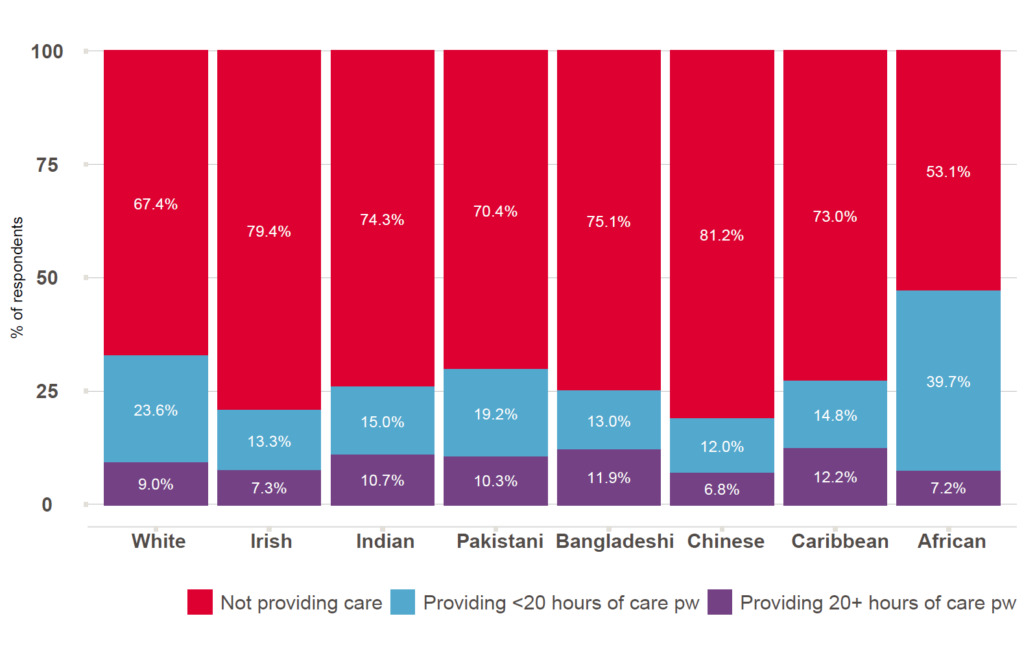

Some black and minority ethnic groups are more likely to be providing more hours of care

During the second wave of the pandemic, nearly half of respondents in the African group (47%) reported some form of caring. Bangladeshi, Caribbean, Indian and Pakistani groups had the highest proportion of respondents providing 20+ hours of care per week. This data shows that carers are from a diverse cultural background. Therefore, the type of support and how this is implemented needs to be tailored to take into account cultural differences (Akiya Trust, Greenwood et al) . Figure 3: Caring status by ethnicity during the second wave of the pandemic

Note: Even though the Understanding Society benefits from ethnic minority boost sample, black and ethnic minorities groups are still underrepresented in comparison to the UK population. Accessible version or click image for larger version.

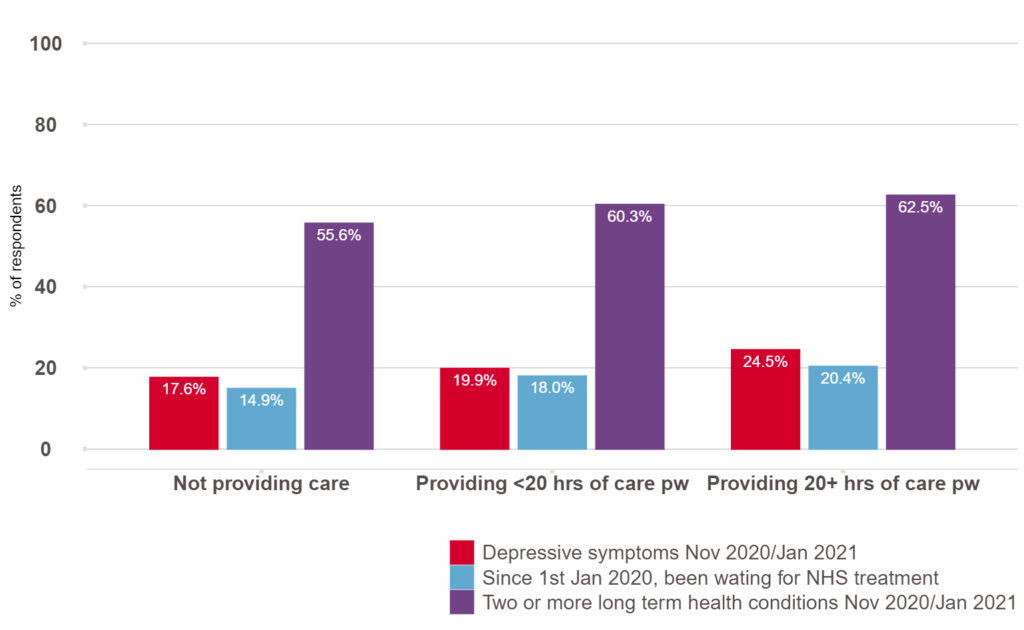

Carers are at increased risk of poor health, especially those providing more hours of care

Providing more hours of care or providing help with personal care have previously been linked to poorer mental health and greater risk of some physical health conditions. A similar pattern is seen for those providing unpaid care during the second wave of the pandemic. Over 60% of people providing 20+ hours of care per week reported having two or more long-term conditions and over 20% have been waiting for NHS treatment during the pandemic (Figure 4). Those providing more hours of care are likely to have complex needs themselves and might require support to manage their own health alongside caring responsibilities. Figure 4: Health conditions and health care access by caring status during the second wave of the pandemic

Accessible version or click image for larger version.

What are the implications?

The UK Government’s Carers action plan 2018 to 2020 noted the need to recognise, value and support carers. The 2019 NHS Long term plan promised greater recognition and support for carers. A key element of this is improvement in the identification of carers in primary care and better support for them to manage their own health care needs. Our findings confirm previous reports that many people have taken on new or additional caring responsibilities since the start of the pandemic and they reinforce the need for identification and support for carers.

Caring responsibilities are a social determinant of health and the impact of caring may vary by the context in which caring occurs.

We found inequalities in who provides care, the type of care provided and health outcomes of carers. Women, particularly those responsible for childcare and from some minoritised ethnic groups, are more likely to be providing more hours of care per week. The physical and mental wellbeing of those providing 20+ hours of care are worse than those providing no care or less than 20 hours of care per week, so they may have complex health needs of their own.

The support offered to carers needs to account for the social context of caring (such as other responsibilities, financial support available to them, household context, values and practices of their communities and definitions of caring – Akiya Trust, Greenwood et al, Public Health England) and needs ensure that those providing more hours of care can be identified to help manage their own health and wellbeing alongside their caring responsibilities.

The demand and burden of unpaid caring is directly influenced by the current structure of the social care system. There are fundamental issues in access, quality, workforce resilience and provider sustainability in the social care system which will continue to impact unpaid carers. The number of older people receiving formal social care services has decreased whilst the need for care has increased over time. Government funding is only allocated to those with the highest needs and lowest means, so others have to fund their own care or rely on friends and family for their care.

Unpaid carers provide essential care so let’s recognise and support the invaluable contribution they make.

About the authors

Anne Alarilla, Fiona Grimm and Mai Stafford are in the Data Analytics team at the Health Foundation, an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and health care for people in the UK.

Mai is currently involved in a programme of work on inequalities in health and health care. After studying maths as a first degree, she trained in medical statistics and then completed a PhD in social epidemiology at UCL. She combines her passion for analysing data with a conviction that social factors are key determinants of health and care. Her current projects focus on care for people with multiple conditions, including socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in care. Twitter: @stafford_xm

Fiona is working on a programme of analyses using linked data to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult social care users and staff. She also has an interest in open analytics and in developing open ways of working, to increase reusability and reproducibility across the health data science community. Fiona’s background is in biomedical research. After studying biochemistry at ETH Zurich, she completed a PhD at the Francis Crick Institute in London. Twitter: @fiona_grimm

Anne is one of the UK Data Service Data Impact Fellows 2019 and has an interest in using analytics to explore and highlight the impact of social and ethnic inequalities in health, health related behaviours and healthcare. She is currently working on exploring social and ethnic inequalities in care of people with multiple conditions. She studied psychology at University of Surrey and completed a MSc in Health Psychology at UCL. Twitter: @alarillaanne

The authors would like to thank Jay Hughes and Sarah Deeny from the Health Foundation for their help and support with this project, and Jamie Moore from University of Essex for assisting with the weightings for the analysis.