Blanca Piera Pi-Sunyer discusses her research into the impact of perceived income inequality on adolescents’ mental health.

Economic inequalities can play an important role in how people feel mentally and physically throughout their lives. During adolescence, which roughly spans from 10 to 24 years of age, these inequalities may be especially important. Adolescence is marked by various social changes, such as transitioning from primary to secondary school, and social evaluations by others become highly influential on attitudes, self-judgements and behaviour. Adolescence is also a time when mental health problems are more likely to arise, with 75% of mental health problems first emerging before the age of 24.

What did we want to know?

In this study, we used the UK Millennium Cohort Study (MSC) to examine how adolescents’ perceptions of income inequalities among their friends, specifically whether they viewed themselves as poorer, richer or the same as their friends, or if they were unsure, were related to mental health, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships, at ages 11 and 14.

We were particularly interested in young people’s subjective perception of themselves compared with their close friends, rather than objective measures of family wealth. As the social environment changes during adolescence, social comparisons become an important tool for understanding ourselves during this period of life. It is possible that adolescents are especially concerned with how they perceive their economic position in relation to their friends’, over and above their overall objective socioeconomic status.

Why is the data from the MCS useful for this?

Information about many people from different backgrounds might tell us something about individual differences.

The MCS has followed over 19000 young people from different backgrounds and different parts of the United Kingdom from birth until their early 20s. The MCS dataset could therefore be a good tool to understand how different individual experiences are related to differences in development over time.

Availability of both person-level measures as well as population-level measures.

The MCS includes many different types of information about each person, such as population-level information, like how many parks there are in a neighbourhood, as well as person-level information, such as nutrition, health, and peer and family relations. This means that researchers can use this data to understand how development occurs within local social contexts, such as friendships and families, as well as how larger social structures, like neighbourhoods, might influence our development.

What did we find and what could it mean?

Adolescents who perceived themselves as poorer than their friends reported more difficulties than other groups

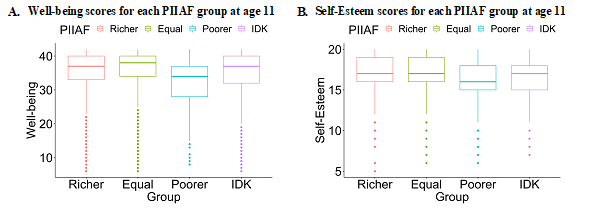

We found that mental health difficulties and victimisation (being bullied) were higher for those adolescents who perceived themselves as poorer than their friends compared to adolescents who did not feel this way. For example, on average, adolescents aged 11 who perceived themselves as poorer than their friends had 11% lower well-being than those who perceived themselves as the same, and 8% lower than those who perceived themselves as richer. Similarly, they reported self-esteem scores that were 10% lower than both adolescents who perceived themselves as the same and those who perceived themselves as richer.

The relationship between perceived income inequalities and mental health is likely influenced by many factors that might amplify or diminish how we view ourselves in relation to our friends. For example, it might be the case that factors like the quality of our friendships, support from family and teachers, or neighbourhood resources, are related to social comparisons in distinct ways. However, the overall effects we found in our study might help us understand how similar experiences, such as those of individuals who perceived themselves as poorer than their friends, can reproduce over populations and over time, and potentially be related to worse outcomes across these populations.

Adolescents who perceived themselves as the same as their friends had the best outcomes.

Mental health and interpersonal difficulties were lowest in adolescents who perceived themselves as the same as their friends. For example, those adolescents aged 11 who perceived themselves as the same as their friends were victimised less and bullied other children less, had lower peer problems and difficulties with externalising behaviour, such as conduct problems and hyperactivity, and reported higher well-being than both adolescents who perceived themselves as poorer and those who perceived themselves as richer.

Therefore, for some outcomes, one possibility is that adolescents who feel economically different from their friends might think that this could risk their group belonging, which is related to distress and negative feelings.

The figure shows (A) well-being and (B) self-esteem scores for each perceived income inequality amongst friends (PIIAF) group, including richer (red), equal (green), poorer (blue) or I don’t know (purple). Those who perceive themselves as poorer than their friends show lower average scores compared to other groups. Those who perceive themselves as the same as their friends show highest well-being scores.

Perceived income inequality amongst friends was related to changes in being victimised across adolescence.

We found that perceived income inequality was related to mental health difficulties in a similar way at age 11 and at age 14, and therefore perceiving oneself as poorer at age 11 did not mean that difficulties were even worse later in adolescence. In fact, we found that, on average, adolescents were victimised less at age 14 compared to when they were 11, and this change was greater for adolescents who perceived themselves as poorer than their friends at age 11. Specifically, adolescents who perceived themselves as poorer reported being victimised 17% more than those who perceived themselves as the same as their friends at age 11, and this difference decreased to 6% by age 14.

Adolescence is a period of social transition when friends and larger peer groups might both be changing. It is likely that attitudes, self-judgements and behaviour, such as perceived income inequality, will depend on the people and environments we compare ourselves to (e.g., peers, friends, neighbours, cultural norms, etc.), and to what extent economic social norms are important in our particular culture. Close relationships might have a stronger influence on behaviours than more distant relationships, which could mean that friends might hold a more meaningful role in influencing our behaviours and self-judgements than wider social groups.

What might this mean moving for future research in this area?

The relationship between social and economic inequalities and mental health during adolescence is complex and context dependent. The results highlight the need to design studies that capture the changing association between perceived income inequalities, changing social groups, individual experiences and mental health trajectories across adolescence.

Together with the development of innovative methods, large datasets like the UK MCS could contribute to designing studies that can effectively address these important questions.

One of the main obstacles in psychological studies is having data from enough people to be able to find meaningful relationships between things we want to know. As the field moves towards understanding how development is related to the experiences of people within their social contexts and social structures, we need large datasets to be able to measure the large number of ways in which people and their environments can differ.

For example, many recent studies suggest that the risk of developing mental health problems is different between genders, age, socio-economic groups and ethnic minority groups. Large datasets allow us to assess how the combined experiences of individuals, including their intersecting identities, together relate to their development.

Researchers need to collaborate with pedagogical experts to inform how social integration interventions can consider the important role of economic social comparisons amongst young people, particularly in close environments, such as friendships, but also in different environments, such as in schools and larger peer groups, neighbourhoods and countries.

The research presented in this blog post is based on Blanca’s recent publication which can be viewed online.

About the author

Blanca is a second year PhD student in Psychology at the Blakemore Lab based at the University of Cambridge. Blanca’s research aims to understand the role of social connectedness in self-judgements and mental health during adolescence. Blanca has a background in psychology and social sciences (Psychology Major in BSc Politics, Psychology, Law and Economics, University of Amsterdam, 2018) and in cognitive neuroscience (MRes in Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, 2019).

Follow Blanca on Twitter: @PieraPiSu

This blog post contributes to our ongoing work looking at Mental health in data.