In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

In this five-part mini series, Joe Allen gets us thinking about the challenges and ethical implications of using Twitter data.

This is the second part of a five-part series on the ease and ethics of utilising Twitter data, based on a talk I gave at the NCRM Research Methods e-Festival.

In the last post, I explored the audience’s reactions to an example of “socially good” use of Twitter data. In this post, I will be looking at the audience’s reactions to an example of malicious “for profit” use of Twitter data.

Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

All data used in this blog post is available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

To begin, I introduced my audience to the following industry scenario.

Scenario 2: A large tech company has scraped Twitter data on the locations you visit, how long you spend there and how often you visit. They are using this data to profile you and target you with effective location-based adverts.

In this scenario, Twitter data has been scraped by industry, for profit. I asked my audience, and invite you as readers here, to consider the following questions before I share my own reflections:

- Is it okay for Twitter data to be used in this way?

- If you were given the option, would you consent to your data being used for this study?

- How would you feel if a business reached out to you to thank, inform or compensate you for your public data in scenario 2?

In this scenario, I’m intending to get people thinking about malicious use of data. The tech company’s targeted advertising is a huge misuse of public data. Whilst some methods of scraping Twitter data enable socially good research (as in the example explored in my last post), they can also unfortunately enable less desirable scenarios like this one. In this instance, we are reminded of how important context is in the decision of giving consent.

Here are the responses my audience gave to the above questions during my talk.

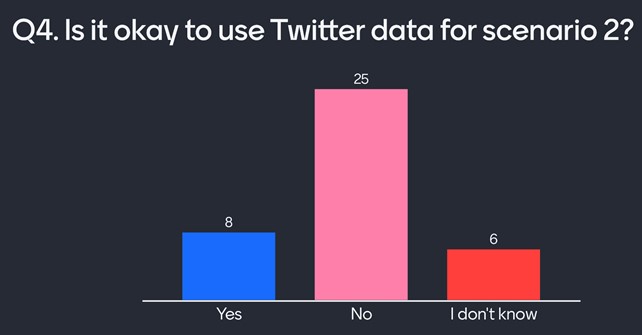

Q4: Is it okay for Twitter data to be used in this way?

Some of the audience members are confident that this data is public, and hence anyone should be allowed to use it. Most users do not like this use of Twitter data, despite this being the way all major social media companies make their money.

Mentimeter responses to Q4

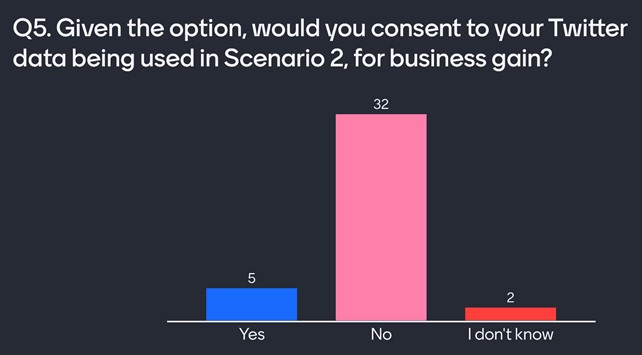

Q5: Given the option, would you consent to your Twitter data being used in Scenario 2?

Unfortunately we cannot fully control our own data. Without being asked to “donate” our data, the way in which businesses use it can sometimes seem akin to theft, as they monetise public Twitter data without compensating users. Users don’t tend to like this, and the end-product can seem manipulative to users. As shown in the Mentimeter responses below, the majority of attendees would not consent to this type of Twitter data use.

That said, some users agree that our data is the price we pay for using social media services. In signing up for an account, we relinquish control of our data and in a way we become part of the product.

Mentimeter responses to Q5

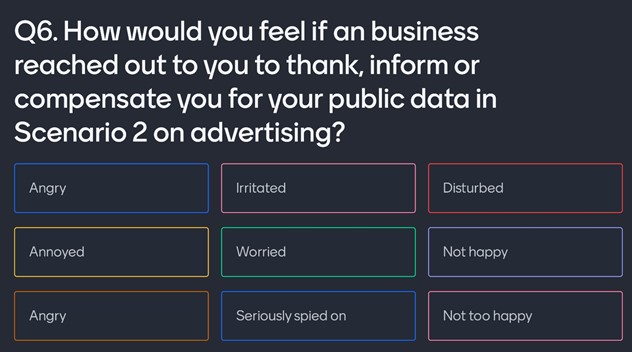

Q6: How would you feel if a business reached out to you to thank, inform or compensate you for your public data in Scenario 2?

When asked to think about this question, responses from my audience clearly showed they disliked Scenario 2. Most users report feeling “Irritated”, “Angry”, “Spied on” and similar.

Thankfully, GDPR now protects users in this scenario. However, businesses will still scrape user data to predict stock prices, political outcomes, and beyond. They simply do it silently.

User anonymity may well be protected, but is it right that Twitter data can still be used in this way?

Mentimeter responses to Q6

Conclusion

In this example of “malicious” use of data, we see just how important the context of the use of our data is when it comes to consent. Conditional consent simply does not exist on modern social media – it is the social media platforms that get to choose whether users have a valid reason to access data.

In my next blog, I will be discussing consent and ethical reviews in academia.

Check out the whole series as it becomes available below:

- Part 1 : Should we use Twitter data in academia?

- Part 2: Should industry have access to Twitter data?

- Part 3 : Is using Twitter data ethical?

- Part 4 : Who is responsible for Twitter data?

- Part 5 : What is next for Twitter data?

All data used in these blog posts are available on the UK Data Service GitHub.

About the author

Joseph Allen is a Research Associate at the UK Data Service, based at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at the University of Manchester. For the last year Joe has been focusing on making Twitter easier to use, whilst also exploring the ethics of this access.

Feel free to contact Joe at Joseph.allen@manchester.ac.uk or on Twitter @JosephAllen1234.

Featured image by Alexander Shatov on Unsplash