Katrin Metsis, Research Fellow in the Population and Behavioural Science Division at the University of St-Andrews, discusses her research using census microdata to understand the challenges of persisting health inequalities in young people.

Katrin Metsis, Research Fellow in the Population and Behavioural Science Division at the University of St-Andrews, discusses her research using census microdata to understand the challenges of persisting health inequalities in young people.

A very brief history of health inequalities

In the United Kingdom, the concern with the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and health dates back to the 1800s.

The 1851 census data was used to tabulate deaths from all causes among men by occupation; in 1978, Michael Marmot and colleagues published the first Whitehall study, which paved the way for the Social Determinants of Health approach. After the Black Report was published in 1980, health inequalities became an important policy and research agenda.

Yet, despite this long history and growing evidence, significant health inequalities remain. In this blog post, I will discuss what these inequalities look like among young people today.

The challenge

In 2025, two reports that draw our attention to the persisting health inequalities were published: the World report on social determinants of health equity and the second Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing.

Both reports remind us that while health inequalities persist, they are not inevitable – and that with the right policies, data and action, good health for all is possible.

Why investigate health inequalities among young people?

Approximately 70% of premature deaths among adults are related to behaviours initiated during adolescence. However, 10–24-year-olds do not have many clinical conditions compared to other age groups, and this is thought to be one reason why attention has been focused on young children and adult populations.

At the same time, many risk factors for non-communicable diseases are present at this age and importantly, adolescence offers a unique developmental period to modify trajectories towards future health.

Investment in 10–24-year-olds will benefit today’s adolescents, the adults they will become and their future children.

And why did we use data from the UK censuses?

Measuring socioeconomic position among young people is challenging as traditional indicators of education, occupation or income are not yet appropriate at this age.

Moreover, health inequalities research needs to include all population groups, but we know that those most affected by adversity are often not represented in surveys. Using microdata files of the UK censuses, accessed by the UK Data Service, offers one option to address these points.

The box below outlines the variables included in the census microdata files that helped us to address the following research question: What can different measures of socioeconomic position tell us about health inequalities in young people?

Microdata files of the UK censuses: detailed population-level information and validated measures

National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification (NS-SEC): groupings of occupations that share similar employment relations and conditions which are important structuring factors in modern societies. This classification includes all population groups regardless their labour market activity.

Highest qualifications: knowledge-related assets.

Household reference person (HRP): the member of a household who is the ‘lead’ of the family. In sociological research, family members are thought as having shared resources and decision-making processes.

Self-reported general health: a validated measure that captures functional and psychosocial aspects of individuals’ lives and predict future health outcomes.

Comparing 2001, 2011 and 2021 censuses showed consistent socioeconomic patterning of general health:

In our first study, we identified consistent socioeconomic patterning of poor health among young people over the period of twenty years; this was despite the general health question being different in the 2001 census.

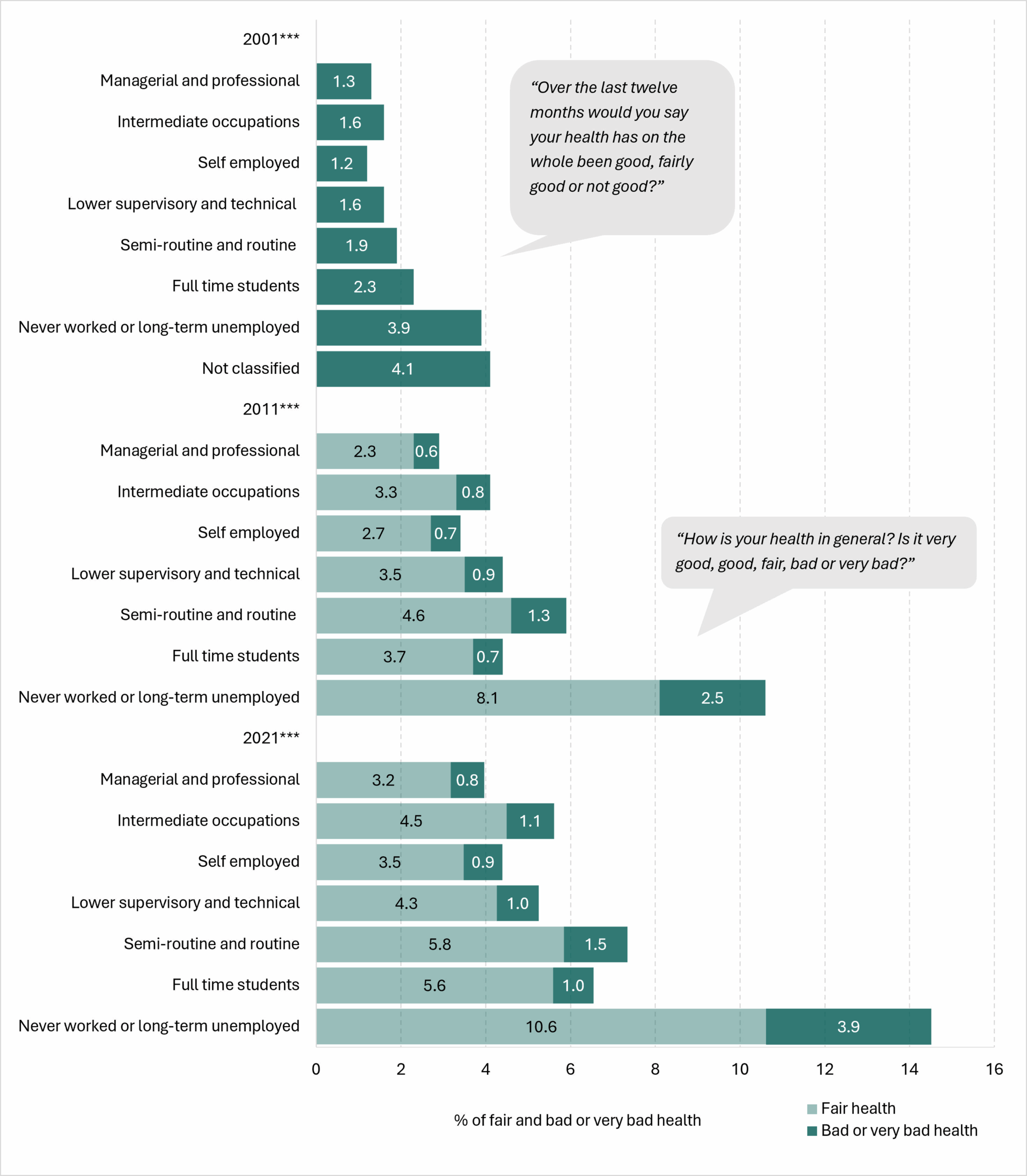

Importantly, our findings identified young people from families where the household reference person was categorised as ‘never worked’ or ‘long-term unemployed’ as having considerably higher rates of poor general health compared to their peers across all three censuses. Figure 1 illustrates this pattern.

Figure 1 – Percentage of poor health among 10-20-year-olds in the 2001, 2011 and 2021 censuses

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

In 2001, 3.9% of young people from the families where the household reference person was categorised as ‘never worked’ or ‘long-term unemployed’ had their health reported as ‘not good’. This compares to 1.3% among their peers from managerial and professional households. Another group of young people from the households where the reference person’s job could not be classified had even higher rate – slightly over 4%.

By 2021, this gap remained. The share of poor health among young people from the households of ‘never worked’ or ‘long-term unemployed’ reference persons had increased to almost 15%; the respective figure among their peers from managerial and professional households was 4%.

How household and individual factors shape health

To look more closely to the differences in general health between socioeconomic groups, we used microdata files of 2021 census for England and Wales.

We changed the age categorisation so that we could use three indicators of socioeconomic position:

- NS-SEC of the household reference person for 10–18-year-olds

- Individual-level NS-SEC for 19-29-year-olds

- Highest level of completed qualifications for 19–29-year-olds

The first allows us to estimate the association between young person’s health status and household-level socioeconomic position, while the two latter ones describe the association with individual’s own socioeconomic position.

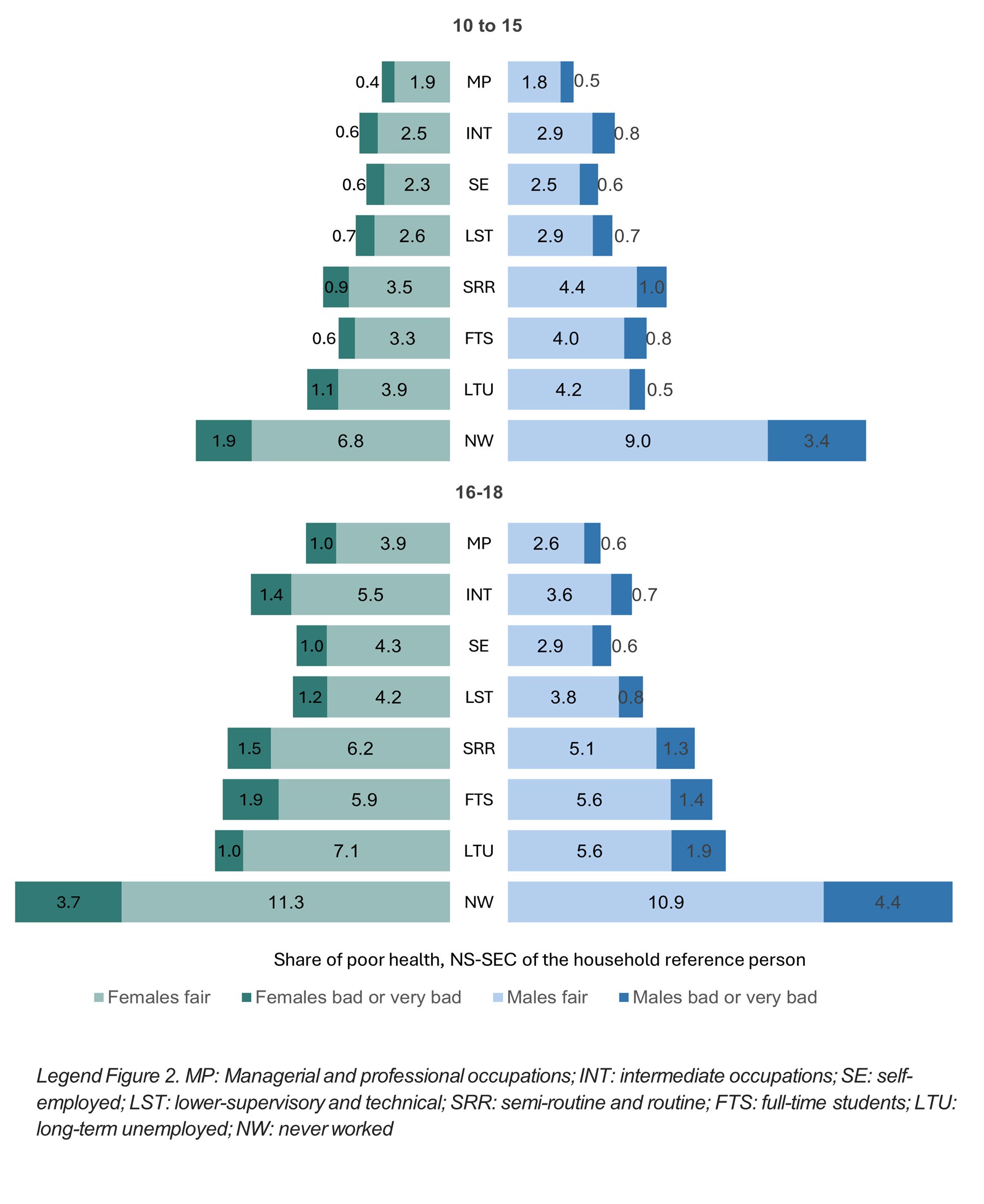

Figure 2 shows the share of males and females when data was grouped by the socioeconomic status of the household reference person.

Young people from ‘never worked’ households presented with the highest share of poor health. This patterning was already evident among 10–15-year-olds and persisted after logistic regression analysis controlled for the effect of age, household-level deprivation of education and housing, and region.

Figure 2 – Share of poor health among 10-18-year-olds by the socioeconomic position of the household reference person, 2021 census data

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

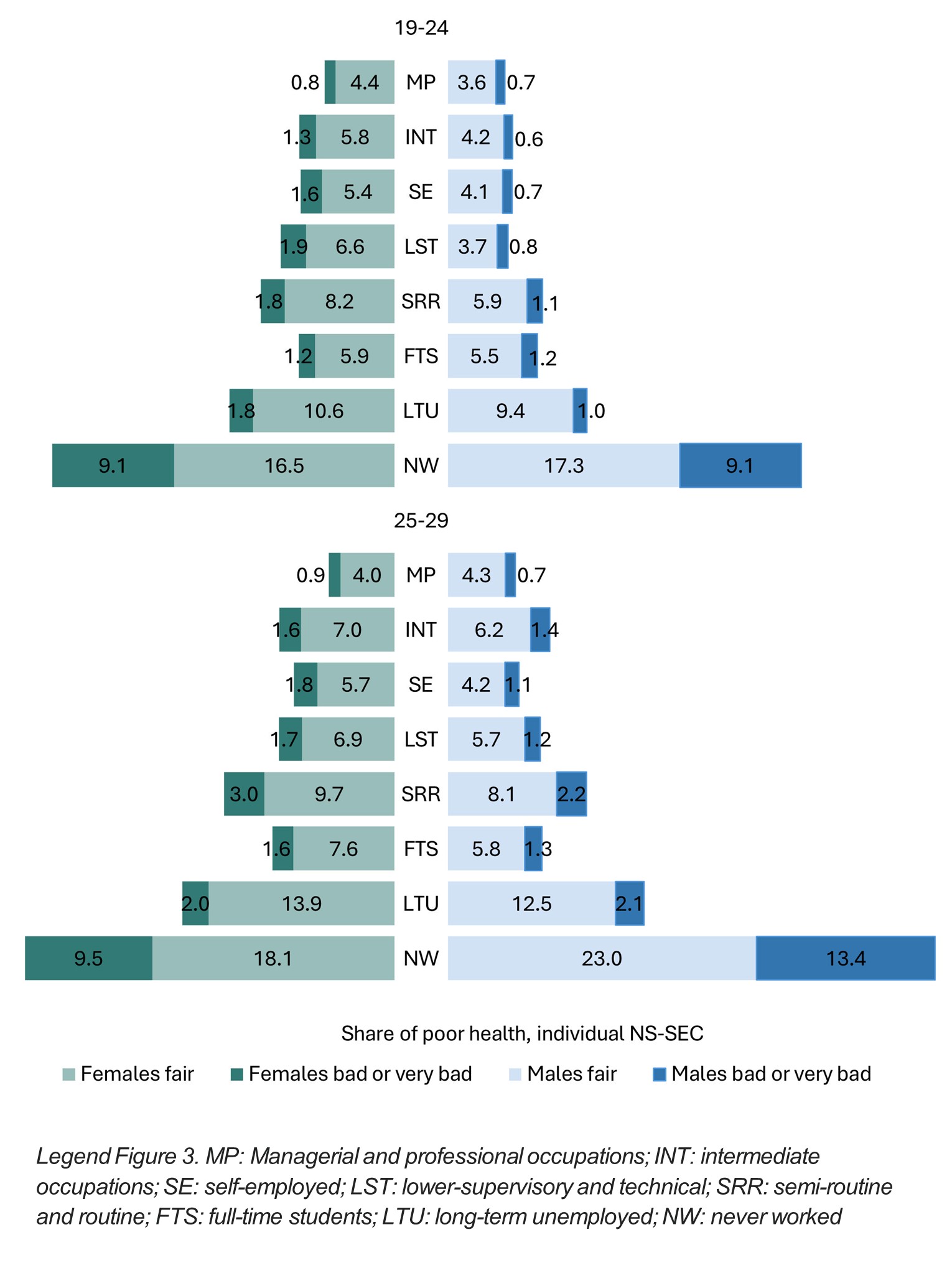

Figure 3 shows the results for 19-29-year-olds when we grouped the data by the individual occupational status. Again, we observed a clear socioeconomic patterning of health with young people from the most advantaged group of managerial and professional occupations reporting the lowest levels of poor health.

Figure 3 – Share of poor health among 19-29-year-olds by the individual NS_SEC group, 2021 census data

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

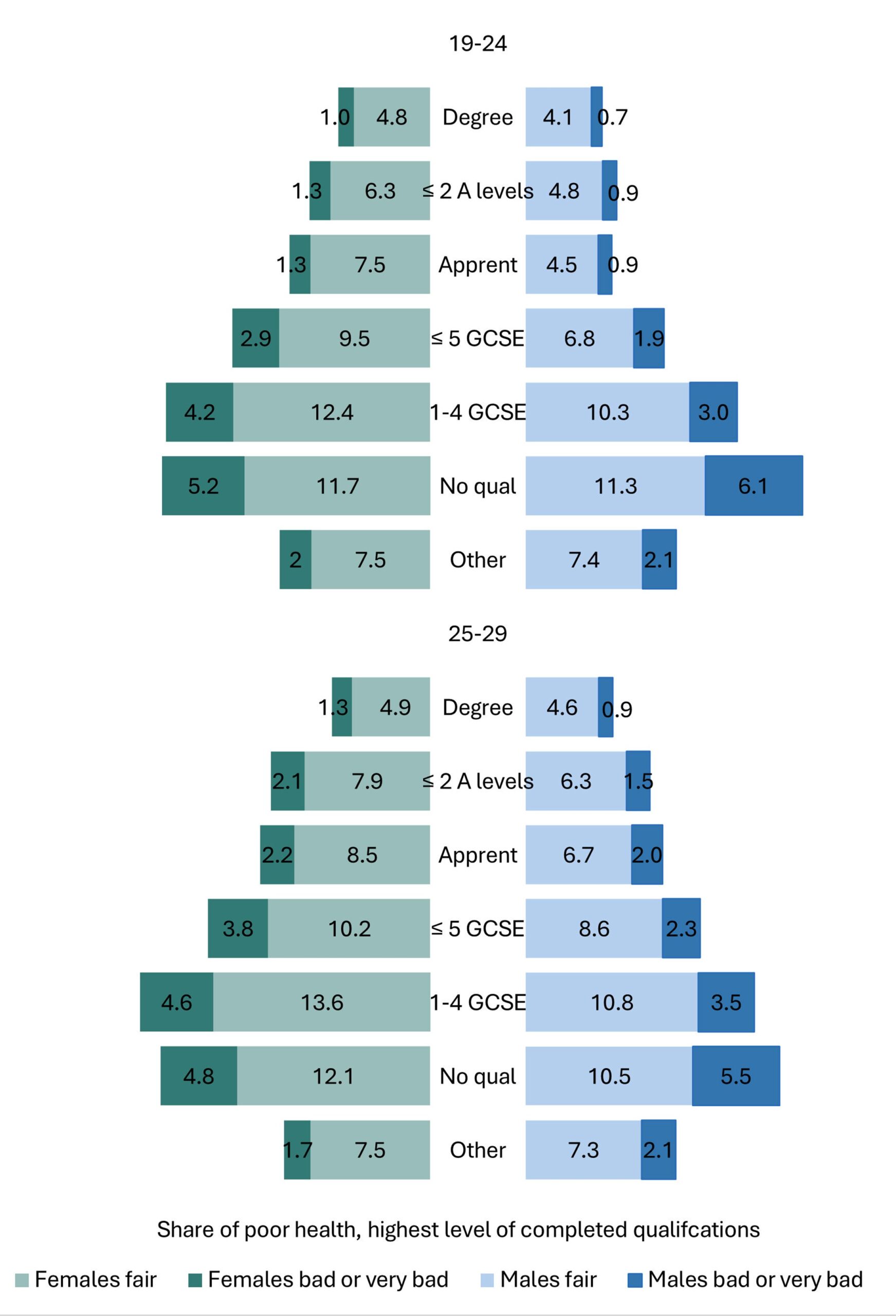

Figure 4 below displays the share of poor health by the second individual-level indicator, the highest level of completed qualifications. Here, the highest share of poor health is reported by those with ‘no qualifications’ or with only 1-4 GCSEs.

Figure 4 – Share of poor health among 19-29-year-olds by the the highest level of completed qualifications, 2021 census data

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

How about differences between males and females?

We did observe differences between males and females. Overall, females report higher levels of poor health. However, among 10–15-year-olds, when data was grouped by the socioeconomic position of the household reference person, males have higher share of poor health. The only exception is those from managerial and professional households, and their share is equal with females.

Next steps

We are in the process of completing the analysis that counts for the disability status. Inclusion of disability reduces the odds of reporting poor health in particular for those who are categorised as ‘never worked’. However, the impact of socioeconomic position remains statistically significant.

Socioeconomic position matters: how can meaningful impact be made from the census data research?

This research demonstrates once again that despite evidence and attention, health inequalities persist among young people. So, the aim should now be to translate those findings into meaningful actions.

Methodological impact: usefulness of census data

UK census microdata is representative of all population groups which is important in health inequalities research. Also, the inclusion of methodologically developed measures of socioeconomic position and health allows researchers to explore the possible mechanisms of health inequalities. In this study, we observed similar socioeconomic patterning of health over the period of twenty years, and across three different indicators of socioeconomic position.

Conceptual element of impact: identification of most disadvantaged groups

Compared to their peers, young people from residual occupational groups of ‘long term unemployed’ and ‘never worked’ have much higher rates of poor health. Next steps of this research show that part of this is explained by disability; however, this finding also points to the structural barriers faced by disabled people when they try to access education or employment.

Knowing that self-rated general health predicts future health outcomes, and (young) people conceptualise health as a holistic concept, we advocate for targeted interventions to change the health pathways of young people who are coming from less favourable conditions.

Reflecting on the complexity of influences on health, Välimaa (2000), as discussed in Metsis et al. (2025), remarked:

“Many things influence health, mental balance, physical balance – everything. There are so many things, you cannot say what influences it and what doesn’t”

About the author

Katrin Metsis is a Research Fellow and doctoral candidate at the University of St Andrews.

She is a social scientist with background in nursing. Her PhD is looking at the health inequalities among young people, and how data from the UK censuses and large-scale surveys can be used to identify the patterning of health. Katrin’s PhD is co-supervised by Professor Frank Sullivan, Dr Jo Inchley (University of Glasgow), and Dr Andrew James Williams (University of Edinburgh).

Prior to starting her PhD Katrin worked on different projects including evaluation of the new models of care in primary care, people’s willingness to share health data from wearable devices, and conflicts of interest in health care. Before moving to St Andrews in 2017, Katrin worked as a research assistant at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine at the Centre for Maternal and Newborn Health.

Other stories you’ll find interesting

Comment or question about this blog post?

Please email us!