Professor Jake Anders is Principal Investigator of the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities (COSMO) study. In this post, he shares insights and opportunities from the study’s second wave of data collection.

Professor Jake Anders is Principal Investigator of the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities (COSMO) study. In this post, he shares insights and opportunities from the study’s second wave of data collection.

The COVID Social Mobility and Opportunities (COSMO) study was established to help track the unique experiences of a cohort — who were in Year 11 and aged 15–16 during 2020/21 — whose education was substantially affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and with little time to recover before taking their next steps.

We set out more details about the founding of the study in this previous Data Impact blog.

A major aim of the study is to continue following the experiences of this cohort as they start to navigate the complex array of options available once they reach this age. Wave 2, data from which are available through the UK Data Service, provides the first opportunities to do this as young people plan and reflect on their upcoming opportunities.

Post-18 opportunities and aspirations: shifting horizons

Now that Wave 2 is available, it is possible take advantage COSMO’s longitudinal design. By following the same cohort members through their post-16 transitions this opens up the potential for richer analyses than those possible with simple cross-sectional data.

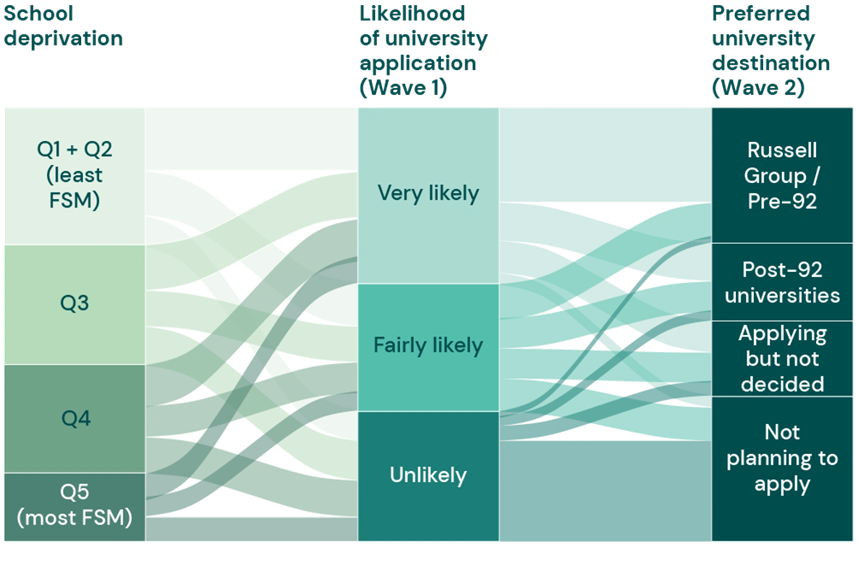

We have taken advantage of this to look at a range of their experiences including, for example, understanding trajectories in university plans as shown in Figure 1, as well as understanding any changes in and persistence of impacts on subjective wellbeing.

Figure 1: University plans over time by socioeconomic background

Larger version / Accessible version

We have also taken this perspective to understand continuing changes in participants’ shifting plans. In Wave 1, most young people reported that they altered their education plans (64%) and career plans (60%) as a result of the pandemic. Among these, the extent to which plans changed varied.

At the extreme, almost one in ten (8%) young people described their education or career plans as having changed ‘completely’ due to the pandemic. And these changes due to the pandemic appear to predict ongoing flux in young people’s main education/employment activity. Those who reported complete upheaval in their plans at Wave 1 were around twice as likely as their peers to have gone on to report a change in their status at Wave 2.

As with many recent cohorts, the vast majority of young people say that they plan on studying at university. When asked in Year 12 (Wave 1) whether or not they thought they would apply to university, over two thirds (70%) thought that it was likely they would do so.

When asked what they pictured they would most likely be doing in two years’ time, just under three in five (56%) thought they would be studying full-time towards a degree qualification. In Wave 2, young people were once again asked about their plans and expectations for applying to study at university. Indeed, as they have got closer to the point of making these applications, many young people’s plans will have begun to crystallise.

For many, this includes having either started or submitted an application for university. Over two thirds (68%) of young people indicated that they were intending to study at university and had either started or submitted an application (47%) or were likely to apply to university, even though they had not started an application already (21%).

However, as shown by Figure 2, there is a clear socio-economic gradient to both intent to apply, as well as the types of universities that young people see themselves attending. Among those planning to apply to university, those with parents who work in a higher managerial/professional occupation are around twice as likely (44%) to target admission to a Russell Group or Pre-1992 university as those whose parents work in a routine/manual occupation, or who have never worked (22%).

In the same vein, young people with a parent educated to degree level are also around twice as likely (48%) to hope to study at a Russell Group or Pre-1992 university as those with parents not educated to this level (24%).

Figure 2: Expected university destinations by household backgrounds

Larger version / Accessible version

Of those young people who had already applied or planned to apply to university, one in five (20%) of them plan to live at home during term time if they are successful in getting into their preferred university. Young people’s planned university living arrangements, however, vary by their family background characteristics, with disadvantaged pupils much more likely to plan to live at home than their richer peers.

For example, young people from working class families (33%) were three times as likely as their peers whose parents are in professional or managerial occupations (11%) to plan on living at home. Similarly, those whose parents are not degree-educated (26%) were also significantly more likely to plan to live at home than those whose parents are degree holders (11%).

Young people’s decisions about the education and careers pathways to pursue are likely to be informed by the opportunities available in their local area. Those who plan to live at home while studying at university due to concerns over costs will be more limited in the range of institutions at which they can study.

Placing other socio-economic barriers to one side, young people who live in large parts of the country outside London and want to study at a specialist institution (such as a music conservatoire) would have more limited options than those living in the capital. Similarly, young people looking to pursue some career paths may find this difficult if relevant training opportunities are not available close to their family home.

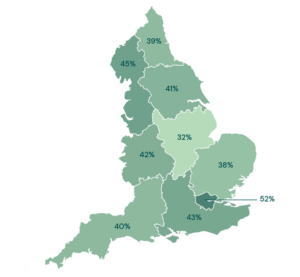

We also sought to understand young people’s perspectives on the opportunities to do the sorts of jobs or training they wanted in their area. Overall, just over two fifths (42%) either agreed or strongly agreed that there were lots of opportunities.

However, as shown by Figure 3, this varied substantially depending on the part of the country in which they live. Young people from London (52%) were far more likely to agree that there were lots of career and training opportunities for them than those from the East Midlands (32%), who were the least likely to agree.

Figure 3: Percentage positive about local career and training opportunities in their locality, by region

Larger version / Accessible version

Mental and physical health: persistent challenges

COSMO data has highlighted an alarming trend that the mental health of the current generation is worse than that of generations before.

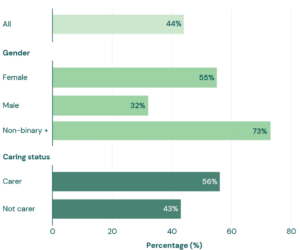

Figure 4 shows the proportion of young people classified as experiencing high psychological distress in COSMO Wave 2. At 44%, this is considerably higher than the 35% with high psychological distress at age 17–18 in the Our Future cohort study (2017) and the 23% at age 16–17 in the Next Steps cohort study (2007).

Figure 4: Percentage classified with high psychological distress by gender and caring status

Larger version / Accessible version

The cohort were asked whether the COVID-19 pandemic is still having an effect on any areas of their life, whether positive of negative.

31% reported that the COVID-19 pandemic was still having a negative impact on their mental wellbeing, while 13% reported a continued negative impact on their physical wellbeing. 23% said there was still a negative impact on their social life. Just over a third (33%) of young people said that the COVID-19 pandemic was still having a negative impact on their education.

Participants were also asked whether they had tried to seek help from a range of sources for a personal or emotional problem.

25% said that in the past 12 months they have sought mental health support. Non-binary+ young people (67%) and females (33%) were more likely to report seeking support with their mental health compared to males (15%).

Unsurprisingly, those classified as experiencing high psychological distress were the most likely to seek support for their mental health, but the majority said they had not sought any support; 39% classified with distress said they had sought mental health support, but 61% had not.

This suggests that perhaps many young people experiencing psychological distress do not know where to go for support, or do not feel comfortable seeking help. It may also suggest they do not have confidence that the right support will be available even if they do ask for it.

Data available from the UK Data Service

Both waves of COSMO data are now available to researchers from the UK Data Service, offering plenty more scope for analyses to understand this generation’s lives and experiences.

The dataset includes detailed educational history and outcomes; mental and physical health measures; information on career aspirations; family background and socioeconomic indicators; as well as the COVID-19-specific experiences and impacts suggested by the study’s name.

There is a lot more information about the study on our website and you can find the whole series on the UK Data Service website.

About the author

Jake Anders is Principal Investigator of the COVID Social Mobility & Opportunities study (COSMO), Professor of Quantitative Social Science, and Deputy Director of the UCL Centre for Education Policy & Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO), University College London.

Jake’s research focuses on better understanding the causes and consequences of educational inequalities, evaluating policies and programmes aiming to reduce these inequalities, and how best to do this evaluation. Jake has published widely across economics, psychology and sociology journals on these issues.

Other stories you’ll find interesting

Comment or question about this blog post?

Please email us!