Naomi Miall, one of our Data Impact Fellows, discusses her research looking at child mental health in the wake of COVID-19.

Naomi Miall, one of our Data Impact Fellows, discusses her research looking at child mental health in the wake of COVID-19.

Charities are reporting that unprecedented numbers of children are experiencing mental health crises in England. The COVID-19 pandemic is often attributed as a contributing factor. The pandemic turned children’s lives upside down, closing schools and childcare centres, disrupting children’s routines and interrupting relationships with friends and family. Our study showed that a trend towards declining mental health among children continued during the pandemic. Unexpectedly, we also found that several inequalities in child mental health narrowed.

Why was the study carried out?

At the start of the national UK lockdowns, many experts predicted that the pandemic would have unequal effects on child mental health. We already knew that wide inequalities existed. Children growing up in poverty were estimated to be three times as likely to experience mental health problems by the time they are adolescents. Teachers and child health experts warned that children living in crowded or poor-quality housing, who had less access to books and toys at home, whose families were experiencing financial stress and food insecurity, would fare particularly badly during the pandemic.

However, early in the pandemic research exploring how child mental health was being impacted was finding mixed results. Several studies observed declines in child mental health, but some found improvements in some groups that were ascribed to a reduction in school- and social-related stress. Furthermore, some studies found that inequalities widened, as was predicted, but others reported little change or even reductions in inequalities. Many of these studies used cross-sectional convenience samples, which make comparisons to the pre-COVID period challenging and risk under-representing minority groups. This mixed evidence made it harder for policy makers and healthcare providers to understand how child mental health needs were changing.

Methods and data

To better understand changes in child mental health during the pandemic we needed more robust data.

Understanding Society is a nationally representative household panel study that has been annually interviewing UK households for more than a decade. Participants are asked about their social and economic lives, their relationships, behaviours, and health. During the pandemic, a sub-sample of participants were asked to complete a series of shorter surveys between spring 2020 and autumn 2021, exploring how the pandemic was impacting their lives.

In the interviews, parents of 5- or 8-year-old children are asked a series of questions about their child’s emotional and social behaviours. Questions include whether they get along well with peers, how often they are hot-tempered, whether they have a good attention span. Responses are combined to calculate an established metric for child mental health, termed the strengths and difficulties questionnaire score. The same questions were also included in the COVID surveys, for parents of 5- to 11-year-olds, allowing average child mental health scores to be compared across time.

This dataset allowed us to explore how mental health and mental health inequalities among UK children had changed over a decade, including over a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, using over 16,000 observations from over 9,000 children. Firstly, we described how average mental health scores among 5- and 8-year-olds changed between 2011 and 2021, across the whole population and among different sub-groups to explore inequalities. We chose seven different socio-demographic variables to investigate different inequalities. These were sex, ethnicity, family structure, highest parent education, parent employment status, equivalised household income, and area deprivation. We then used a two-level regression model to estimate whether the COVID-19 pandemic modified the relationship between each of the seven sociodemographic variables and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) score, after adjusting for the impacts of age, year and sex.

What did we find?

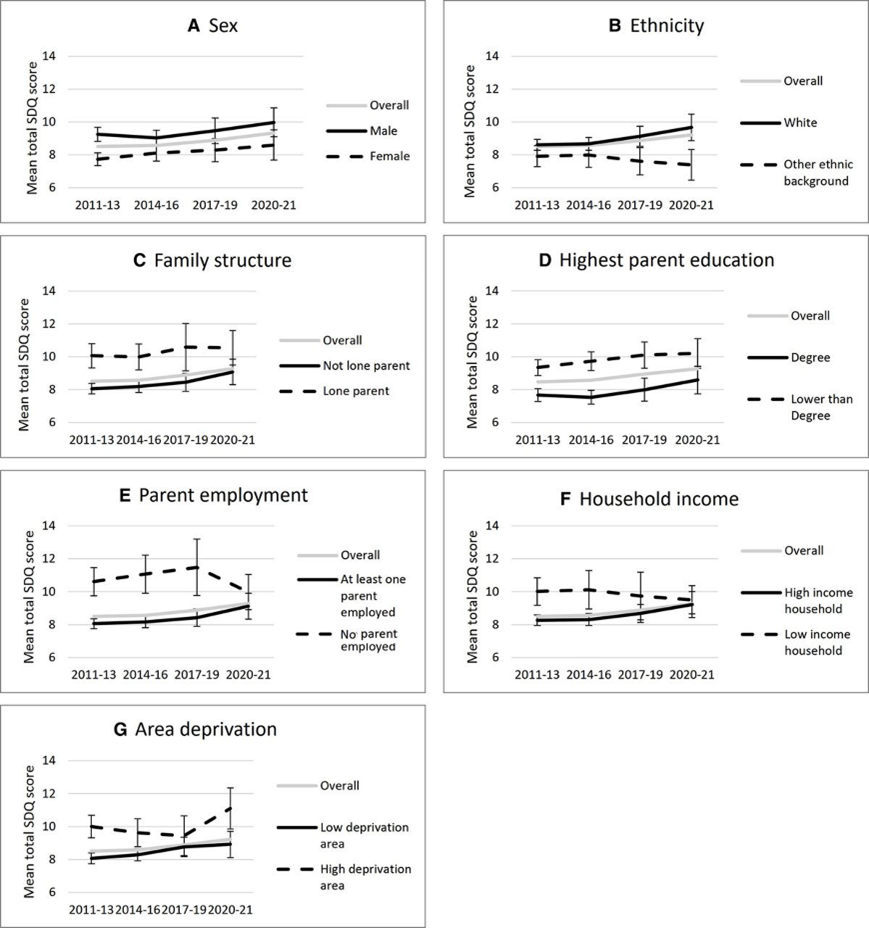

Concerningly, child mental health deteriorated between 2011-2019, with further declines seen in 2020-2021. This can be seen in the rising grey line in Figure 1. Unexpectedly, the greatest declines during the pandemic were often seen in typically advantaged groups, including children in higher income households, with degree-educated parents, with employed parents and who were not in single-parent households. This pattern meant that inequalities narrowed, but around a worse average level of mental health.

Figure 1: Changes in the average Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) score of UK 5-year-olds between 2011 and 2021. Higher scores represent more severe mental health symptoms. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The greatest change was seen in relation to parent employment, as shown in Graph E of Figure 1. Children with unemployed parents were 2.18 times more likely to experience borderline or abnormal mental health scores before the pandemic compared to those with employed parents, but during the pandemic this reduced to 1.38 times as likely. In other words, the size of the inequality reduced.

One hypothesis to explain why these socio-economic inequalities in child mental health may have decreased is that the disruptive and difficult experiences, common during the pandemic, were already a part of life faced by children living in poverty. For example, experiencing poverty can entail social isolation, reduced access to services, and experiences of uncertainty and disruption. These experiences share similarities with some of the negative consequences of the pandemic lockdowns. However, these were more likely to be new experiences for children from advantaged backgrounds during the pandemic. In other words, the pandemic may have meant that the experiences of many children became more similar to some of the experiences that disadvantaged children were already facing. These explanations are speculative and further qualitative research is needed to understand how the pandemic was experienced by families from different background and communities.

Not every inequality that we studied narrowed. Throughout the last decade, boys experienced slightly worse mental health than girls, and children living in more deprived areas also faced worse mental health. These inequalities were maintained during the pandemic. Furthermore, white children (encompassing both white British and white minority ethnic groups) faced worse mental health than children from other ethnic backgrounds throughout the study period, and worryingly this inequality widened during the pandemic.

What are the implications?

Poor mental health in childhood places a significant strain on children and families, and also has ramifications for later health and wellbeing in adulthood. Poor mental health is a known barrier for children to engage in education, for their ability to build social identities and relationships, and can constrain children’s physical, cognitive and emotional development. It is therefore critical that the downwards trend in the mental health of children as young as five can be reversed. This requires sustained investment in mental health services for young people, and crucially in the factors and structures that promote and maintain mental wellbeing.

It is notable that children in more deprived areas experienced consistently worse mental health between 2011 and 2021, highlighting the importance of good quality services and safe spaces to play. Improving the mental health of all children will require cross-sectoral action to improve the conditions in which children grow up.

The full study, Inequalities in children’s mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the UK Household Longitudinal Study, is published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health.

About the author

Naomi Miall is an affiliate researcher at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit at the University of Glasgow, which is where this research was completed, and a Data Impact Fellow with the UK Data Service. Naomi’s research at the University of Glasgow explores inequalities in child and maternal health. Naomi now works at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, on a program to improve global access to HPV vaccination for adolescent girls.