Alasdair Rae uses quantative and qualitative data, including the stories of the people affected, to explore the reality of using public transport to access work from poorer areas of the UK.

Alasdair Rae uses quantative and qualitative data, including the stories of the people affected, to explore the reality of using public transport to access work from poorer areas of the UK.

Three hour commutes: for ‘fun and profit’?

The Department for Work and Pensions suggests that jobseekers should look for jobs up to a 90 minute commute away. In a tweet from 2016, the Department suggested that jobseekers could ‘travel, for fun and for profit’.

On one hand, this doesn’t seem such a radical suggestion, because it could in theory widen the range of possible job opportunities.

https://twitter.com/DWP/status/734444069808689152?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indy100.com%2Farticle%2Fthis-dwp-advice-about-commuting-three-hours-a-day-is-mindblowing–WkxUzUayX7W

In reality, we know that commutes are often very far from ‘fun’ and they can also seriously eat into ‘profit’.

In fact, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that for many people ‘fun and profit’ are the last words they would associate with the daily grind of commuting, and travelling 90 minutes each way to a low paid job may not even be economically viable.

For residents of low income neighbourhoods this may particularly true, for a number of reasons.

In a report for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation with colleagues at Sheffield Hallam University, we explored the topic in more depth and found that for residents of low-income neighbourhoods the geography of employment opportunities is often highly restricted due to poor transport. This is not surprising, yet it is too often overlooked.

Using a variety of data sources, including Census data on travel to work and employment status, we were able to look at this across the UK’s poorest neighbourhoods.

Put very simply, poor public transport is a significant barrier to employment for many people.

Our study employed both quantitative and qualitative methods. A major part of this was calculating how far people could travel from some of Britain’s most deprived neighbourhoods using public transport, and then comparing this to where jobs are located.

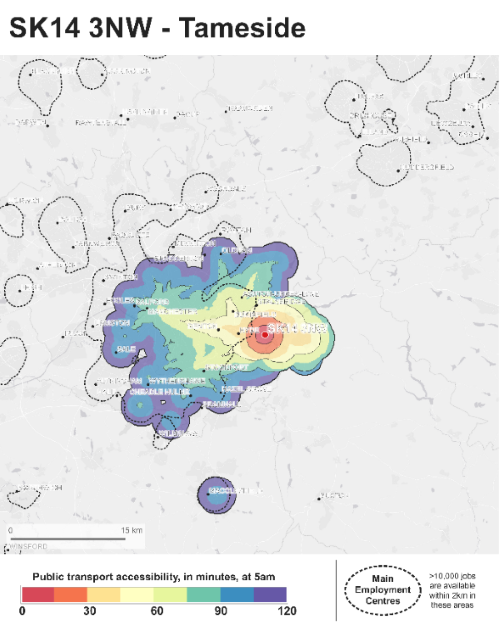

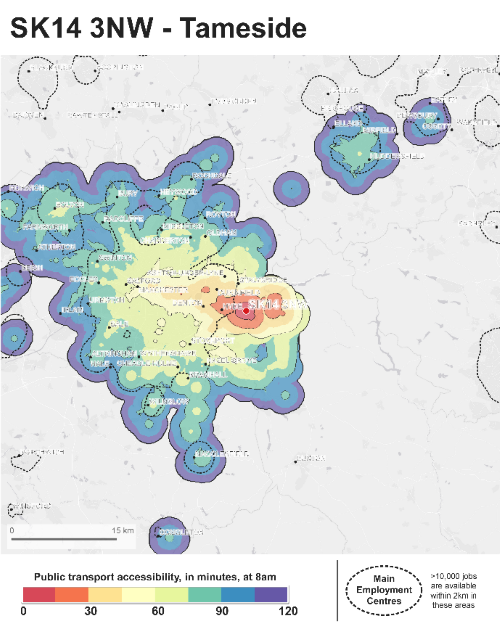

In these maps, we can see how far it is possible to travel at 5am and 8am from the SK14 3NW postcode area in Hattersley on the eastern edge of Greater Manchester. The dotted lines show where most jobs are located and the different colour bands represent 15 minutes of travel.

At 5am

At 8am

Leaving at 5am, travel horizons on public transport are very limited and it would take you more than an hour to get to the city centre, just 12 miles away.

At 8am things improve slightly, yet it’s still at least a 50 minute journey, and these are best case scenarios, assuming no delays. We have provided maps for around 200 of the most deprived locations across Great Britain using the same approach. The story is similar nationwide: for many people living in deprived neighbourhoods, jobs can be hard to reach.

Local voices: what did people tell us?

But of course looking at the data only tells us so much, and that’s why it was really important to speak to residents. In order to make this meaningful and manageable, we decided to focus our efforts in six areas across the country, two each in and around Glasgow, Leeds and Manchester, as you can see in the map below.

The research team from Sheffield Hallam University conducted 79 interviews in these areas, and the results reinforced the message the data seemed to be suggesting: that a 90 minute job horizon is neither realistic nor reasonable.

This sentiment was widely shared, particularly for workers with caring responsibilities (e.g. children in school who need to be picked up). Others noted how it could extend the long working day. For example, a resident in Harpurhey in Manchester commented that:

“I’d be willing to travel any distance, it’s more time … [The Job Centre Plus expectation) It’s just silly, you’ve got three hours travel time on top of a job, so you do a 12 hour shift, 15 hour day, where are you supposed to sleep in that?”

Harpurhey, female, aged 35

Feelings on the issue sometimes ran high, with residents providing ample evidence to suggest that there is a very real link between connectivity and poverty. For example, one resident in Seacroft in Leeds noted that:

“They have tons of work, big industrial estate, but there’s no bus service, it’s about 13 miles away. I do not understand why they build a big estate where there’s no transport, that’s like tough, if you haven’t got a car.”

Seacroft resident, male, aged 49

While another in Port Glasgow commented on the issue more forcefully:

“[It’s] got to be the worst bus service out, they’re shocking, they’re either five minutes late or five minutes early, sometimes they don’t even show up.”

Port Glasgow resident, female, aged 20

Of course, it should not be a surprise that we find a link between poverty and connectivity, yet it is too often overlooked in discussions about how to help residents of low income neighbourhoods gain and hold permanent employment.

In many cases, a precarious labour market combines with poor transport options to create almost insurmountable barriers to employment.

The important question, of course, is what we could do about it.

We don’t think the solutions are easy, yet we do believe something can be done to resolve the situation for residents of low income neighbourhoods and we therefore made a number of policy recommendations, based on our in-depth analysis of the issue.

What should be done? Some policy recommendations

We believe transport-related barriers to employment could be addressed through a wide range of measures. However, a ‘pick and mix’ approach would most likely lead to poor outcomes. Strategic and coordinated action is required.

Therefore, we propose four overarching priorities, to improve the employment prospects for people living in low-income neighbourhoods:

- integrating transport and employment policy to enable employment support agencies to play a vital role in supporting clients to understand travel choices and how to navigate them as part of their return to work; action is required across spatial scales, but there is much that agencies working at local or city regional level (especially local authorities, Jobcentre Plus and other employment support providers, transport bodies and combined authorities) can do to develop solutions;

- implementing bus franchising or ‘strong’ models of cooperation, to address transport-related barriers emerging from a deregulated public transport system that all too often fails to meet the needs of low-income users;

- making public transport more accessible and more accountable through technology – particularly through open data (including fares) and real-time data on public transport – to understand issues, develop solutions and communicate information to users;

- developing longer-term spatial planning frameworks and tools to embed sustainability, density and transit-oriented development principles that better connect places of residence and work.

Alasdair Rae, @undertheraedar, is a Professor in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the University of Sheffield. He’s an urban and regional analyst whose work covers a wide range of topics, including land use, housing, transport, commuting, land use, GIS, geovisualisation, neighbourhoods, internet search data, and megaregions.

Put simply, he attempts to use maps and data to understand the world a little bit better, and recently this has led to the publication of his Land Cover Atlas of the UK and a series of outputs on the English green belt. In 2017 he won the Royal Statistical Society’s ‘Stat of the Year’ award and the RTPI’s Sir Peter Hall Award for Wider Engagement. He publishes his work in academic journals and books, but also regularly features in the print and online media, and occasionally on TV. Extracts form his work can be found on his blog, at www.statsmapsnpix.com.

The full research team for this work was: Richard Crisp, Ed Ferrari, Tony Gore, Steve Green, Lindsey McCarthy, Kesia Reeve and Mark Stevens (all Sheffield Hallam University).