In this post Michela Vecchi and Catherine Robinson share their research looking at skills mismatch in the UK.

The UK job market is becoming increasingly challenging, in part due to the demands of new technologies and the shift to a greener economy. Thus, having greater variety in one’s skill-set is likely to improve an individual’s employment opportunities.

In this environment, university graduates should fare particularly well as they develop a range of technical, creative and social skills that can help them to find the right job, that is a job where such skills are valued. However, estimates from the ONS reveal that on average 30% of graduates in the UK are overqualified or mismatched, that is they are not employed in graduate jobs.

In our analysis we expand the measurement of mismatch to account for graduates’ field of study and their unobserved skills. The main objective is to address the issue of graduates’ skill heterogeneity and to better understand the nature (and consequences) of skill mismatch. Being in the right job is good for individuals, who will likely earn higher wages and experience higher levels of job satisfaction; it is also good for the economy, as the evidence suggests that a good skill match promotes productivity and innovation performance.

Which data and methods were used?

We construct two measures of the skill mismatch, using the 2017 Annual Population Survey – an annual survey including working adults in the UK. The first approach follows the ONS methodology which compares worker qualification levels with those required for an occupation. For example, working as a barista usually requires compulsory level of education (GCSE). A graduate employed as a barista is an example of skill mismatch or overqualification, as he/she is unlikely to use the skills learnt as part of a degree in their job. This type of mismatch is also often referred to as vertical mismatch, as it is only based on the level of qualification or number of years of education.

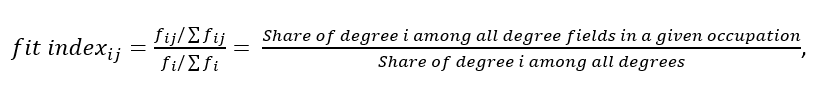

Our second measure focuses on the type of education and uses information on the different degree fields within occupations. Indicators of this type are usually referred to as horizontal measures of mismatch. To construct our new indicator, we adapt the methodology commonly used to analyse countries’ international specialisation to analyse skill mismatch. Our new field intensity index (fit index) is defined as follows:

where ‘i’ identifies the degree field and ‘j’ stands for occupation.

The fit index defines a benchmark for the computation of the skill mismatch. A graduate (k) is horizontally mismatched if the fit index is less than 1. A value of the fit index > 1 indicates that a particular degree is intensively used in a specified occupation. The larger the value of the index, the more intense the demand for a particular field of study.

A critique often addressed to analyses of this type is that education is not a perfect measure of graduates’ skills. Indeed, measuring skills is challenging as they are often unobserved. Our attempt to capture skills beyond education follows previous work in using information on the skill content of occupations, provided by the ONS.

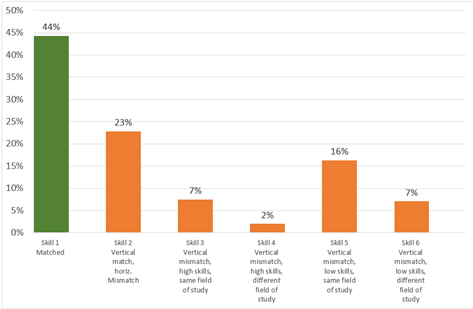

Our underlying assumption is that the skill content of occupations reveals more accurately the skill of graduates. Using information on different types of mismatch and skills, we can map all graduates over six skill types. At the top of the scale, we find fully matched graduates (Skill 1), while at the bottom we find low-skilled graduates in non-graduate jobs without a field of study match (Skill 6).

Our findings

Figure 1 presents the proportion of UK graduates, mapped over the six skill types. This shows that approximately 44% of graduates are perfectly matched, and employed in a graduate job which requires their degree field. About 23% percent are working in a graduate job that requires a different degree field (Skill 2), hence they are only horizontally mismatched. Using a terminology introduced by Chevalier, approximately 9% can be defined as genuinely mismatched as they have developed high level skills, but they are not in a typical graduate job (Skill groups 3 and 4); the remaining 23% of graduates are apparently mismatched because, despite holding a degree, they have not developed high level skills.

Figure 1 Proportion of graduates in each skill type Source: Annual Population Survey, 2017, ONS

The group on the far right of the chart (skill group 6) represents graduates that are particularly penalized in terms of wages. In fact, our estimates show that they earn approximately 40% less compared to those with a perfect job match. This wage penalty, on the other hand, is substantially lower for graduates who are only horizontally mismatched (approximately 2% for skill group 2). A pure horizontal mismatch does not impose a strong downward pressure on wages but, at the economy level, it indicates that investment in education is lost as the skills learnt as part of a degree are not used in the workplace. Our analysis also suggests that part of the often-discussed lack of skills in the UK economy might be due to skill misallocation.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, our study suggests different avenues for policy intervention. For graduates with a field of study mismatch, better orienteering of programmes before entering university and during university studies, accompanied by relevant work experiences and internships, may reduce this type of mismatch.

Next to this misallocation, our results show that there is a considerable proportion of graduates who, despite investing in tertiary education, have not developed graduate-level skills. In this case the challenge is to raise both observable and unobservable skills, as well as providing valid alternatives to university education that can better fit individuals’ skills. Recent policy interventions may go some way in addressing this, with the introduction of new T-level qualifications, the growth in work-based learning through the employer-led higher and degree apprenticeships courses and moves within universities to develop more skills-based education developments.

Among factors associated with the probability of a mismatch, we find that, next to the ‘usual suspects’ (quality of institution, degree classification, gender, age, marital status), being foreign-born and graduating from a non-UK institution as being strongly and negatively associated with the probability of finding a good job match. This may be related to language barriers, lower reservation wages and poorer knowledge of the UK job market.

From the demand side, it is possible that employers in the UK do not have adequate knowledge of education systems in other countries. Policy interventions directed at improving the allocation of foreign skills within the UK market could be another measure to reduce the skill mismatch and promote a more efficient use of resources.

About the authors

Michela is a Professor of Economics at Kingston University. She has over 20 years’ research experience and has worked on a variety of topics within the productivity and labour economics spectrum. Her current main areas of research are skill mismatch and productivity, human capital, skill biased technical change, dance, wellbeing and performance.

Kate is a Professor of Applied Economics at Kent Business School. Her research focussed mainly on firm level performance and factors which influence it, ranging from foreign direct investment to social enterprises; technological change to skills and migrant workers. Most recently, Kate has worked on skills mismatch as part of an ESRC funded research project, co-investigated with Michela Vecchi