Stuart Mills continues his series on data policy theory, concentrating here on different views to what data are.

Stuart Mills continues his series on data policy theory, concentrating here on different views to what data are.

What are data?

For many of us, the first idea which comes to mind is that thing we pay for as part of our monthly phone contract.

Alternatively, some of us might associate data with the rows and columns of a spreadsheet, or with internet titans like Facebook or Google or Amazon.

The trouble with data is, when we stop and think about a firm definition or fundamental quality that delineates simple observations or pieces information from data, we might find ourselves stuck.

Aren’t all data information, and isn’t all information gathered through observation?

In political science, Srnicek and Williams offer an idea called folk politics.

Folk politics could also be called common sense politics; a non-exact, learned understanding of how politics works. Of course, this understanding could be inaccurate when examined, but generally, folk politics is a good-enough guide.

A similar argument might be made about data.

For our daily lives, having a strong concept of what data are is probably not necessary. If your mobile phone, spreadsheet and social media work, what’s the problem? But it’s helpful to have an analytical framework for thinking data when asking more pressing questions: who controls data, who owns data, what is the value of data, and so on.

This philosophical definition of data (which is probably a bad name) is what I’m going to talk about in this post.

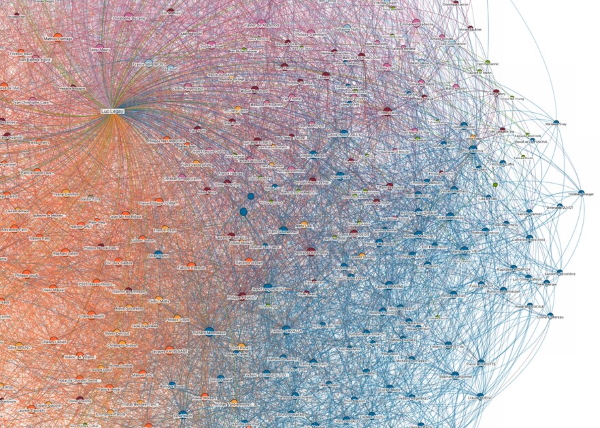

Image: a web of data

The Non-Neutrality Principle

A good question to begin with is not the question “what are data?” but instead:

are information and data the same thing?

For several authors, the answer to this question is no.

In their essay series Raw Data is an Oxymoron, media historian Lisa Gitelman argues that information only becomes data when it is conceived and recorded as such.

From this perspective, we might imagine information existing everywhere all the time, waiting for someone to capture it that it might become data. What’s more, choice is of vital importance; as Gitelman writes, raw data is an oxymoron. There is always some choice as to what to measure and what not to measure, and thus data carries some human bias and exists for some purpose or intention.

Legal scholar Teresa Scassa has called this idea the non-neutrality principle.

To answer the question are information and data the same, the non-neutrality principle implies no, because information is some objective metric about something, while data is a collection of subjectively gathered information.

For example, Apple’s maps service recently adjusted the borders around the disputed peninsula of Crimea, now showing Crimea as Russian rather than Ukrainian.

We know that Crimea exists; we know where the peninsula is located and how big it is and what type of terrain makes up the territory. But the data one receives from Apple maps is reflective of non-informational choices. Someone has chosen to label Crimea as Russian, just as a choice has also been made for the past several years to not label it Russian, and just as all borders represent choices about the division and interpretation of geographic information.

Data is thus non-neutral, and – as Gitelman attests – raw data is oxymoronic.

The Combination Argument

The combination argument is a subtly different take on the question: are information and data the same thing?

Another legal scholar, Christopher Rees, argues that data isn’t so much about conceiving of information as data, but instead is the product of combining information.

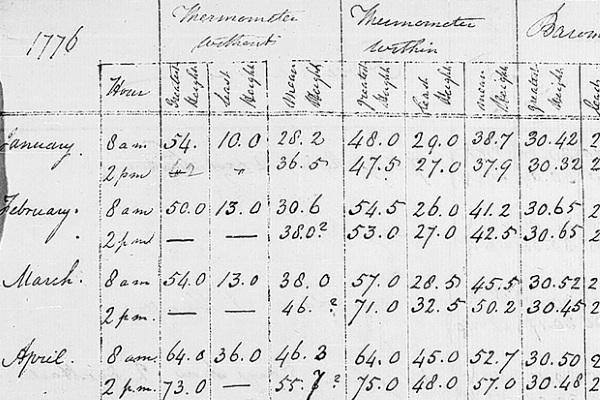

For example, if I have a column of numbers ranging from 0 to 100, I have no idea what these numbers mean in aggregate. That’s not to say that these numbers aren’t informative; I can identify whether a 6 is a 6 or a 4 is a 4. The trouble is, I don’t know what 4 or 6 relate to!

But if I introduce more information, maybe I can discern some meaning and practical use from these numbers.

Maybe I add the information that these are test scores, and then add another column of information which contains some names? By combining information, it would seem I’ve produced some data about individual test scores.

This is the combination argument.

Image: handwritten data in table format

In my opinion, the combination argument is much nicer than the non-neutrality principle because it’s much closer to the folk definition. Under the non-neutrality principle, data ceases to be a tangible object and becomes much more metaphysical.

The combination argument appeals to our common-sense idea of data being something tangible by explaining where data comes from.

This explanation fits into our immediate observations of the world: we provide, say, Facebook with our information, and they combine it with other information to produce the data for their services. From a political economy perspective, this is quite an interesting interpretation, because we can start thinking about how data is produced, and who has claims to the value of this productive effort.

However, I’d argue the combination argument and the non-neutrality principle are not that different. In fact, I’d go so far as to say the combination argument is actually a subset of the non-neutrality principle.

This is because non-neutrality trumps combination.

If I have a list of names, I may not know where those names came from, or if the order of those names matters. But I could still do something with this information.

I might have a theory that John is often a very common name and use this list of names to investigate this theory. I’m still combining something to treat this information as data, but I’m not combining information together. Instead, I’m combining a piece of information (the list of names) with an act of intention (my theory) to conceive of the information as data.

Another example: Facebook may well combine pieces of information together to produce data, but what pieces of information is a non-neutral choice Facebook makes; a decision which is based on Facebook’s commercial interests.

The combination argument is an elegant way of thinking about the production of data, but it does not in fact escape the non-neutrality principle.

Should We Ignore Folk Data?

Respecting the non-neutrality principle, the answer to the question “what are data?” may be:

information about which choices are made?

But is this a final answer? As with almost all of philosophy, probably not.

For instance, I’ve spoken a lot about data, but I’ve never drawn a distinction between personal or social data, and natural data. If an equation predicts the interaction of some variables in the physical world, and we collect data about those variables to test the equation, are those data non-neutral? The answer is, I don’t know…

It’s also helpful to ask is this new definition of data – information about which choices are made – useful? I think it is, mostly because it helps us think about how (or whether) data are produced, which impacts policy questions. But it’s also extremely vague, and one might be tempted to defer back to the folk definition.

When thinking about the digital economy, it’s wise to remember many people will make decisions based on folk definitions, and these decisions (whether we agree with them or not) also impact various policy questions.

Image: mouse pointer hovering over follow button

For example, the idea that data are comparable with oil or currency doesn’t mesh well with the non-neutrality principle or the combination argument, but is a very common idea in the digital economy. And if we think this comparison is fair, it has implications for

- how we ‘transact’ with our data

- what services we receive ‘for’ our data

- what protections we should expect

These questions are at the heart of digital political economy and form the basis of the political theory of data, which I will discuss in a later blog post.

But we can’t arrive at a political theory without considering the philosophical theories which tackle the question: what are data?

Read Stuart’s introduction to this blog series.

About the author

Stuart Mills is a PhD researcher at the Manchester Metropolitan University Future Economies Research Centre. His research includes behavioural economics, behavioural public policy, hypernudging and data politics.