Hei Wan (Karen) Mak, UCL research fellow, on the health benefits of volunteering and how Understanding Society data provides new insights into the links with age, cohort, and neighbourhood deprivation.

Hei Wan (Karen) Mak, UCL research fellow, on the health benefits of volunteering and how Understanding Society data provides new insights into the links with age, cohort, and neighbourhood deprivation.

Why does volunteering matter?

Globally, more than 1 billion people are thought to volunteer, and in Britain approximately 2 in 5 adults undertook voluntary work in 2019. The scale of UK volunteering has increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, with over a million people registering as volunteers with national/local organisations and more than 3000 self-organised mutual aid groups formed in the first months of 2020.

It has been estimated that volunteers contributed £15bn to the UK economy in 2018, yet when taking into account the wider social value of volunteering, the impacts are considerably greater. For example, volunteering has been shown to help improve mental wellbeing, increase physical activity, enhance social bonds and create social rewards.

Photo by leah hetteberg on Unsplash

Why did we look into it?

Whilst the link between volunteering and social and individual wellbeing is well established, far less is known about how age vs cohort and place of residence affect this relationship. Both factors are known to shape population behaviours and health.

I have been working with colleagues at UCL to understand whether older volunteers receive greater benefits from volunteering engagement, and if so whether this was driven by their age or the year they were born (which involves the change in social meaning of volunteering over time).

We were also interested in whether volunteering and its health benefits varied across neighbourhoods. Understanding this is timely given the increasing place-based funding schemes and the current UK government’s Levelling Up commitment to help create stronger communities through volunteering and community activities.

Identifying volunteers in survey data

To answer these questions, we analysed Understanding Society: UK Household Longitudinal study data. This rich and high-quality data includes information about participants’ socio-demographics, community group participation and volunteering engagement, as well as their health/wellbeing, which has allowed us to consider key variables when examining the long-term relationship between volunteering and mental wellbeing. In addition, Understanding Society provides geo-coded data in which participating households’ addresses are matched to neighbourhood zones (Lower Super Output Areas), enabling us to explore objectively the role of neighbourhoods in survey data.

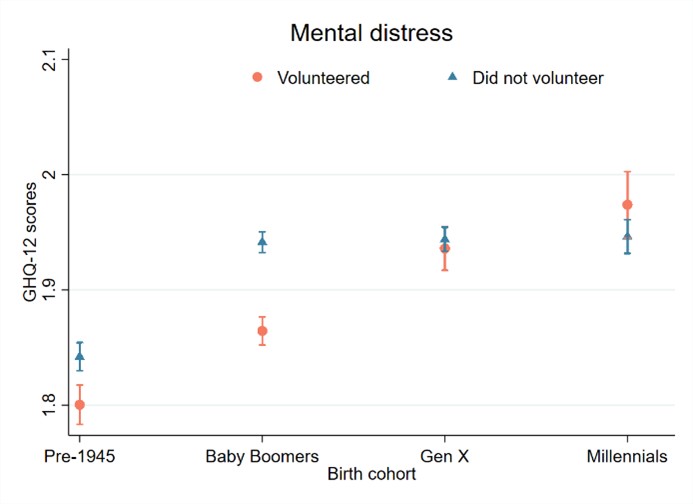

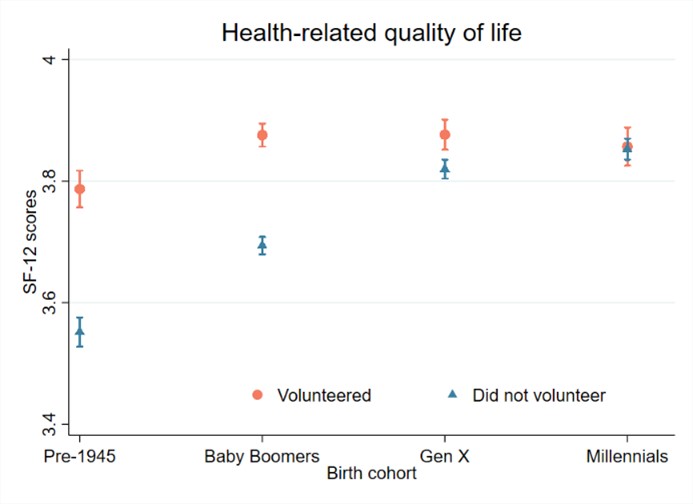

We combined Waves 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 where volunteering engagement was measured. We extracted a sample of adults living in England and examined how changes in their engagement were associated with the changes in mental distress (GHQ12) and health-related quality of life (SF12) (N=10,989). Participants were stratified by their birth cohort: Pre-1945 (born before 1945), Baby Boomers (born in 1945-1964), Gen X (born in 1965-1979) and the Millennials (born in 1980 or after), and by their place of residence measured by levels of area deprivation.

To identify volunteers, we measured their frequency in voluntary work using the following two survey questions:

- In the last 12 months, have you given any unpaid help or worked as a volunteer for any type of local, national or international organisation or charity?

- Including any time spent at home or elsewhere, about how often over the last 12 months have you generally done something to help any of these organisations?

What did we find?

We found that 21% of our sample had volunteered, with a greater prevalence of volunteering among older cohorts. Younger cohorts reported greater levels of mental distress but better health-related quality of life. Volunteers generally experienced lower levels of mental distress and greater levels of health-related quality of life than non-volunteers. These differences were more prominent for the older population (see Figures 1 & 2). Such differences were also more defined in more deprived neighbourhoods, especially for quality of life. Levels of mental distress and health-related quality of life were worse in more deprived areas for both volunteers and non-volunteers.

Figure 1: Volunteering engagement and mental distress by birth cohort

Accessible version or click image for larger version.

Figure 2: Volunteering engagement and health-related quality of life by birth cohort

Accessible version or click image for larger version.

Older generations appeared to benefit more from volunteering

When holding all time-invariant variables (e.g. gender, ethnicity) and important time-varying variables (e.g. age, partnership status, employment status) in constant, increasing one’s volunteering was associated with greater levels of health-related quality of life amongst adults as a whole over a 10 year follow up. But these effects were largely driven by older generations (Baby Boomers and adults born before 1945). Baby Boomers also appeared to benefit more from volunteering as a means of reducing mental distress. There was little evidence that younger adults born from 1965 onwards experience the same outcomes from volunteering.

These findings can be understood through the lens of underlying mechanisms of volunteering, in which some mechanisms are especially relevant for older adults. For instance, voluntary work enables older adults to develop new social networks, social role and group identity. It also provides a structure to volunteers’ lives especially for those who have entered retirement. In contrast, many key ingredients including personal development, relationships, values and identities that link volunteering to health/wellbeing for young adults can instead be experienced through education, employment and family responsibilities.

Yet, the fact that the effects of volunteering varied across cohorts after controlling for age indicated that cohort effects may also play a role in explaining the health benefits of volunteering. Change over time in the social meaning of volunteering, alongside initiatives and programmes that encourage engagements, could potentially influence cohort motives, values and beliefs towards volunteering, their voluntary behaviour, and the associated outcomes. In addition, changes in social and political contexts (e.g. incomes and economic security) could also influence volunteering engagement as well as the levels of engagement, which could in turn affect its associated outcomes.

Wellbeing benefits of volunteering were found regardless of where people live

Whilst previous studies have shown that volunteering engagement rates are generally higher in safer, more accessible and less deprived neighbourhoods, we found that where people live does not influence the association between volunteering and mental health and wellbeing. This finding may reflect a more equal number of voluntary organisations in the least and most deprived areas and a growth of place-based funding streams that encourage residents in deprived neighbourhoods to take part in voluntary and community work, such as through creating safer neighbourhoods, ensuring well-maintained voluntary organisations and providing wide ranging voluntary activities with flexible hours.

However, there are other potential explanations too. It is possible that there was just simply a small neighbourhood effect on the likelihood of volunteering once individual characteristics had been accounted for. It is also plausible that there may be small main effects of area deprivation on people’s mental health and wellbeing. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that volunteering could potentially have benefits for all individuals if it can be introduced to different areas equally.

A time for intervention?

The UK government has recently published the Levelling Up White Paper, which includes a commitment to improving wellbeing and pride in place. Meanwhile, the NHS Long term plan promises to support social prescribing (with volunteering being one of the activities) in primary care and to have at least 900,000 people referred to social prescribing by 2023/24.

Our study provides crucial evidence for the need for effective delivery, and shows that the effect of volunteering on health may last for as long as 10 years (in line with previous research). However, our research goes beyond previous research in showing that older volunteers tend to receive greater wellbeing benefits from volunteering than younger volunteers. Given that age is controlled for in our analysis, our findings suggest that generational social attitudes and changes in how volunteering is portrayed and delivered (e.g. as a means to collectively improve society vs a strategy to promote individuals’ health and wellbeing) could influence not only whether people volunteer, but also whether doing so bolsters health.

Such findings are particularly relevant to the Levelling Up mission. Whilst the government has promised to provide £4m to help create new youth volunteering opportunities, this study suggests that promoting voluntary work as a social endeavour may help motivate people (including young people) to engage. Further, the fact that no neighbourhood effect was detected in our study suggests that the wellbeing benefits of volunteering are likely to be equal across areas with various levels of deprivation.

In this light, it becomes important to ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to participate in voluntary activities and to enjoy the benefits they provide. Our research therefore aligns with and builds on existing work in the field by recommending the following:

- Sufficient financial support: Ensure the availability of the central grant funding, particularly in more deprived local authorities.

- Variations of voluntary activities: Provide wide ranging voluntary activities (including digital volunteering and social action volunteering such as climate change and race inequality) and flexible volunteering hours.

- Sense of community restoration: Create safer, harmonic, close-knit and stable residential environments to build a sense of place attachment and encourage volunteering within communities.

- Applying behavioural science theories to improve volunteering engagement rate amongst individuals with low community opportunities: According to the COM-B behavioural change theory model, people’s voluntary behaviours could be increased through Capabilities (e.g. interpersonal skills, knowledge about the charity), Opportunities (e.g. availability of charity shops, the ease of access there, flexible hours), and Motivations (e.g. family and peer influence).

- Empowering young people through volunteering: In addition to promoting volunteering as an activity to help sustain wellbeing and cultivate skills, it could also be delivered as a means for young people to shape and change their community.

Read the research

Mak, Hei W., Rory Coulter, and Daisy Fancourt. 2022. ‘Relationships between Volunteering, Neighbourhood Deprivation and Mental Wellbeing across Four British Birth Cohorts: Evidence from 10 Years of the UK Household Longitudinal Study’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 3: 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031531

About the author

Dr Hei Wan (Karen) Mak is a research fellow at the UCL Department of Behavioural Science and Health and at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre on Arts and Health. Karen is currently working on projects to explore how arts and cultural community engagements are associated with improvements in mental health/wellbeing and identify the profile of arts/cultural engagers across the UK. Her work involves partnerships with Arts Council England, Historic England, What Works Centre for Wellbeing, and the Social Prescribing Network. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Karen joined the UCL COVID-19 Social Study team to understand the predictors and patterns of home-based arts and cultural engagements.

Featured image by leah hetteberg on Unsplash