Rebecca Florisson, Principal Analyst at the Work Foundation at Lancaster University, discusses the issue of long-term insecure work.

Rebecca Florisson, Principal Analyst at the Work Foundation at Lancaster University, discusses the issue of long-term insecure work.

For millions of workers in the UK, employment in the 21st century is characterised by insecurity. Previous Work Foundation research found that one in five workers in the UK (6.8m) are in severely insecure work, characterised by low pay, unpredictable hours, and a lack of access to rights and protections. Our new study finds that for too many workers, this is not a short-term issue, but something that workers can be trapped in for many years, with often detrimental effects. This entrenched problem not only hampers economic growth but also has profound effects on workers’ well-being, health, and future opportunities.

Our new study examines the likelihood of progressing out of insecure work using the Work Foundation’s measure of job insecurity which was previously described in more detail on the UK Data service blog. We apply this measure to the longitudinal Understanding Society dataset from 2017/18 to 2020/21, allowing us to track insecure workers across a four-year period.

The insecure work trap

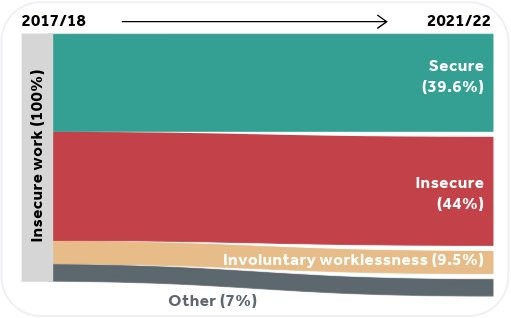

According to the findings, 44% of workers in insecure jobs remain stuck in long-term insecurity over a four-year period. This ‘insecure work trap’ defies the assumption that any job is a stepping stone to better opportunities.

One of the workers we spoke to for this research, Jessica Burns, a 30-year-old mother of three from Salford, enjoys her role at a local Iceland supermarket, but her experience underscores the difficulties of working in a sector where hours and pay fluctuate unpredictably. “Obviously, I never know what I’m going to be paid each week,” she said.

For Jessica, even with a guaranteed 7.5 hours a week, her hours—and by extension her income—are far from stable. “Last week I did two shifts of only four hours, so that’s eight hours. This week, I’ve had four shifts,” she explains. Such variability makes it nearly impossible to plan finances or meet household needs effectively.

The unpredictable nature of Jessica’s work mirrors the wider systemic issue highlighted in the data. Insecure work’s financial precarity often prevents workers from acquiring the skills or stability needed to pursue better opportunities. Moreover, switching sectors— which we found is a key factor in escaping insecure work—becomes particularly challenging for individuals like Jessica, who need flexible arrangements to manage family responsibilities.

Figure 1: Employment status of workers in 2021/22, who started in insecure work in 2017/18

Source: Work Foundation calculations of weighted Understanding Society data Waves 9-13

Getting out of the sector to escape insecurity

Sectoral mobility is a critical factor in helping workers transition to secure roles. Sectors like social care and retail—where jobs are often temporary or short-term—pose significant barriers to progression. In Jessica’s case, despite having the qualifications to work in mental health support, she had to step away from her chosen career to find a role that accommodated her caregiving responsibilities.

This highlights a stark contradiction: sectors struggling with recruitment and retention challenges often lose workers like Jessica, who are capable and qualified but unable to find the flexibility or security they need. Secure roles are more accessible in sectors such as education, transport, and real estate. However, transitioning between sectors requires resources, support, and training that insecure workers often lack.

Safety nets are not adequate for insecure roles

There is an often unhelpful interaction between the benefits system and job insecurity. The previous government’s approach was to get jobseekers into ‘any job’, which has seen people pushed into insecure and low-quality roles for fear of being sanctioned. The ‘ABC’ idea was that people would first obtain ‘any job’ and then a ‘better job’, and following, a career. The findings of this research indicate that insecure jobs are not necessarily a stepping stone to a better job.

Being in an insecure job, in turn affects access to essential benefits. We know from our previous work that those in insecure roles are more likely to be on benefits such as Universal Credit. However, the way these benefits are awarded and calculated are ill-suited to the realities of insecure work. The 5-week wait for the benefit to start can be incredibly difficult to overcome for low- income households, and risks them going into debt. Furthermore, the assessment period calculates the benefit to be awarded based on last month’s pay, which not only fails to account for irregular pay periods, but also importantly introduces a volatility in earnings that makes workers hesitant to take up more hours because they are not certain how this will affect their income. This was also highlighted by Jessica. “UC is a total mystery to me,” she said, pointing to how unpredictable earnings and fluctuating hours disrupt her ability to manage bills or plan her family’s weekly meals.

Supporting the UK workforce to thrive and progress

For workers like Jessica Burns, the day-to-day uncertainty of variable hours and fluctuating pay creates a precarious existence that undermines their potential and well-being.

The new government’s Employment Rights Bill offers hope for tackling the deep-rooted issues of insecure work. Key measures such as banning zero-hours contracts, making flexible working a day-one right, and establishing the Fair Work Agency are steps in the right direction. But as the research and Jessica’s testimony illustrate, the problem extends beyond individual contracts.

Policymakers must address the multifaceted nature of insecurity. We must build on the momentum of the Employment Rights Bill to improve work quality and progression pathways for workers. The first step in doing this is gathering good evidence and using this to set the right targets and monitor progress towards those targets. Our report recommends we bring together a Secure Work Commission to monitor levels of insecurity in the economy and set targets to increase the rate of secure, good quality employment.

Further, Government’s Get Britain Working white paper flags consultations in 2025 on reforming the welfare system. It is key that proposed reforms shift the focus of the Department for Work and Pensions from monitoring claimants and administering welfare conditionality to supporting people into sustained work and incentivising employers to provide more secure jobs.

The Work Foundation at Lancaster University is a think tank dedicated to improving working lives in the UK. Our core mission is to widen access to rewarding, high-quality and secure work. We undertake applied quantitative and qualitative research to tackle structural inequalities in the UK labour market and seek to influence government policy and employer practice.

About the author

Rebecca leads the Work Foundation’s research programme on insecure work. She has expertise in precarity, social mobility and working conditions and applies cross-sectional and longitudinal data analysis to important research and policy questions.

Alongside her role at the Work Foundation, she is a PhD candidate at Queen Mary, University of London, conducting an ESRC-funded study on the impact of precarious work on life course employment trajectories. Previously, she worked at Eurofound in Dublin.