Dr Chris Playford, Senior Lecturer at the University of Exeter, describes his recent study which explores the role of geography in progression to Higher Education in England.

Dr Chris Playford, Senior Lecturer at the University of Exeter, describes his recent study which explores the role of geography in progression to Higher Education in England.

Going to University is an important outcome for many young people and is often a requirement for gaining employment in more advantaged occupations. Numerous academic studies (e.g. Crawford et al.) have explored inequalities in progression to Higher Education according to the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of young people. Concurrently, there is a separate body of research (e.g. Manley et al.) which explores differences in rates of progression according to where young people grow up. Our study sought to explore how the composition of the area in which young people in England grew up influenced whether they progressed to Higher Education, alongside individual-level factors.

Why was the study carried out?

Rates of progression to Higher Education vary markedly across England, with the highest rates in London and the South East of England. In contrast, the lowest rates of progression occur in the North East and South West of England. These regions differ substantially with regard to the geographical situation. In particular, the population density of the South West of England is far lower with many young people in the region growing up in rural and coastal areas. There have also been a series of reports which have identified young people growing up in seaside towns face limited educational and employment opportunities compared to those in towns and cities inland.

Previous studies have not considered differences in the composition of regions of England in understanding progression to Higher Education in conjunction with the socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds of young people. The main reason for this is that many datasets do not support analysis at these levels. Our study sought to do this by using linked survey and administrative data.

Which data and methods were used?

The analysis was based on the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England, also called Next Steps. This is a representative cohort study of 15,770 young people aged 13/14 in England in 2004 and currently includes information up to age 25 in 2016. Three further linkages made the analysis possible. Educational attainment in General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) qualifications at age 15/16 is available with linked National Pupil Database data. Geographical characteristics of the local area in which the young person grew up at age 14, including region and area-level deprivation, are included as supplementary files with identifiers for the Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) provided. We then subsequently linked this to further information on the distance of the LSOA to the nearest coast provided by Wheeler et al. . This enabled us to derive a measure which classified whether the young person grew up in an urban inland, urban coastal, rural inland or rural coastal area. We were then able to estimate logistic regression models adjusting for complex survey design which included geographical and individual-level predictors.

What we found

Young people who grew up in urban coastal areas (seaside towns) were less likely to have attended University by age 25 (40%) than those who grew up in urban areas inland (50%) or rural coastal areas (53%). Once we controlled for area-level deprivation (based on the Indices of Multiple Deprivation) this association was explained. This suggests that deprivation in coastal towns and cities is the reason for lower rates of progression to Higher Education.

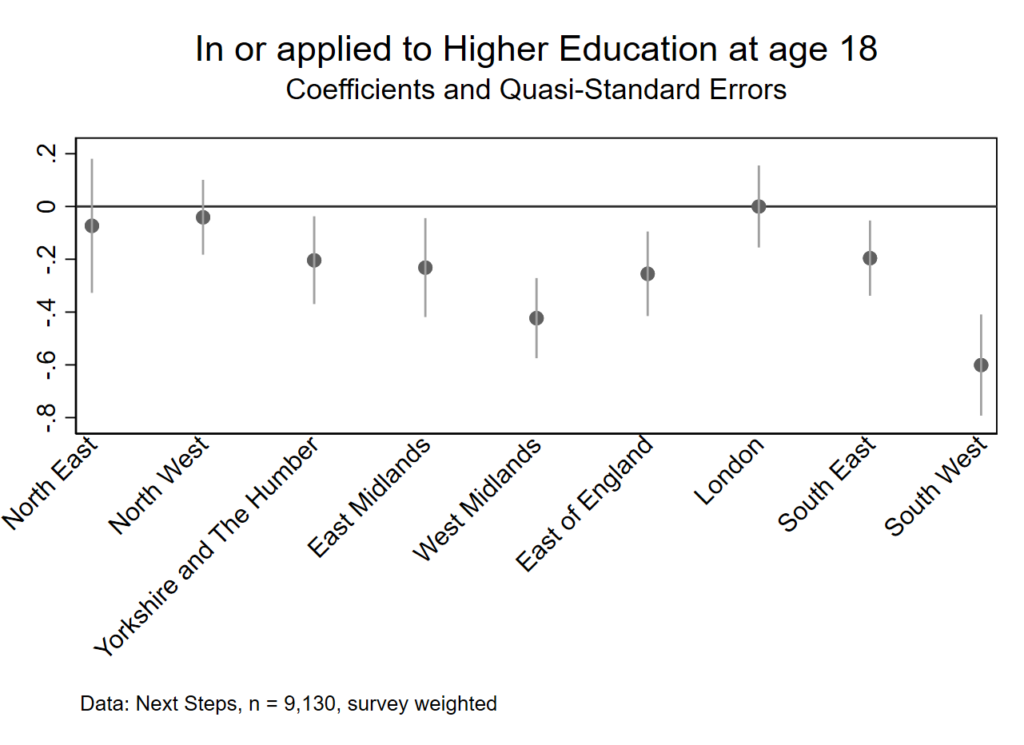

For most regions of England, differences in progression to Higher Education are explained by the geographical and social composition of these regions. For the South West of England though, this is not the case. Young people growing up in the South West of England with similar characteristics to those in other regions are still less likely to go to university than young people in other regions. This is shown in the figure below and is based on a statistical model including relevant geographical and individual-level variables. For most regions, the quasi-variance comparison intervals overlap suggesting differences between regions were non-significant. In contrast, rates of progression to Higher Education in the South West of England remain lower than elsewhere.

What are the implications?

Our research suggested that young people growing up in coastal areas may face different challenges in accessing Higher Education compared to those in urban inland areas. Whilst this may be explained by higher levels of area-level deprivation in many seaside towns, the potential solutions may not be straightforward. In many urban inland areas, young people would not have to leave home to attend University. It is quite possible that outreach work that is trialled in ethnically diverse urban areas, where distances to Higher Education providers are small and there is a greater supply of universities with a wide range of admission tariffs, may not translate well to a more geographically remote region with fewer Universities.

Whether this is the main barrier to progression remains unclear though. Future studies might therefore seek to investigate the exact nature of the educational challenges faced by young people in rural and coastal areas. To answer the question, better understanding of the potential dislocation for young people in more geographically remote areas is required. In particular, our work emphasises the importance of knowing more about the opportunity structures, decisions, and possibilities for young people in growing up rural and coastal regions.

This is a research topic we are intending to pursue further and are seeking future opportunities to do. If this is an area of interest to you, please do get in touch.

You can read the research this blog post is based on here.

About the author

Dr Chris Playford is a quantitative sociologist working in the fields of social stratification and the sociology of education. His research explores the role of family background on educational attainment and employment outcomes with a substantive interest in inequality and disadvantage.