In this post, Dr Lewis Smith discusses data classification and the gendering of consumption through the lens of market research conducted by rail companies in the 1970s.

Data categories seem logically constructed. In reality, they aren’t just logically constructed, they are built on centuries of history, culture, politics and society. It is only by understanding how these forces work together that we can truly understand the implications of a dataset.

In June 2022, Dave Rawnsley wrote an article for the UK Data Service Data Impact Blog on changes to census definitions and concepts over fifty years. As it went on to state, ‘these rules were developed in consultation with interested Government Departments, the Royal Statistics Society, the Market Research Society and the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising.’

Whilst new for the Census, and represented an important economic, political and sociological category, capable of embodying both power and oppression for a number of people in Britain. First and foremost, the ’Housewife’ was an economic innovation which was ‘invented’ as a consumer in the 1950s by marketeers to sell household products. The “housewife” had come to symbolise the stability of Britain’s working class families. Of course, this was captured by one of the most powerful housewives in post-war Britain, Margaret Thatcher, who made much of this symbolic status. She carefully crafted her image as a housewife by being pictured performing the duties of a housewife, washing up, making breakfast, cooking, to show her ‘ordinary’ side.[2] In politics, the “home economy” was just as important as, if not more important than, the British economy.

However, for some this stability had meant oppression, particularly in the age of second wave feminism. Ann Oakley, a well-known British sociologist, described in her 1974 analysis that a housewife’s “primary economic function is vicarious: by servicing others, she enables them to engage in productive economic activity”, and that “instead of a productive role”, she would act as “the main consumer in the family”.[3] For some, the category shoehorned women into a narrow idea of Britain’s economy that suggested that their key role should be as a carer in the family who was principally not an economic producer (like the husband typically was) but an economic consumer.

British Rail and Inter-City

How did this categorisation present itself in marketing through this period? For our case here we’ll be looking at how Britain’s nationalised railway operator, British Rail, made use of market research to attract new consumers to the railway. Nationalised industries are an interesting case in point on their own, as we often assume that ‘market research’ is a tool for the private sector to understand its markets. In reality, there is a long history of public bodies using market research: government departments like the Empire Marketing Board and the Ministry of Information/Central Office of Information were proficient international market researchers – and so were nationalised industries.

After decades of poor ridership and a lot of bad publicity, British Rail underwent a process of managerial change in the mid-late 1960s. By 1970, British Rail had undergone an enormous process of modernisation. As part of this modernisation, British Rail hired a number of different organisations from the private sector to handle its communications.

They recognised that one consumer that had been left out of railway advertising was the “housewife”. Many ads before had featured housewives, but they were not targeted at housewife’s, instead featuring them as token additions. Examining one very small avenue of this campaign, a number of research studies were conducted to ascertain the best ways of reaching the traditional conception of the housewife, including a number of focus groups, panel interviews and questionnaires. In 1972, as part of research into three promotional advertisements designed to “assist in the creative development” of promotional leaflets for the optional travel market, Ogilvy Benson and Mather published a recommendation that there were two interesting avenues for British Rail to take.

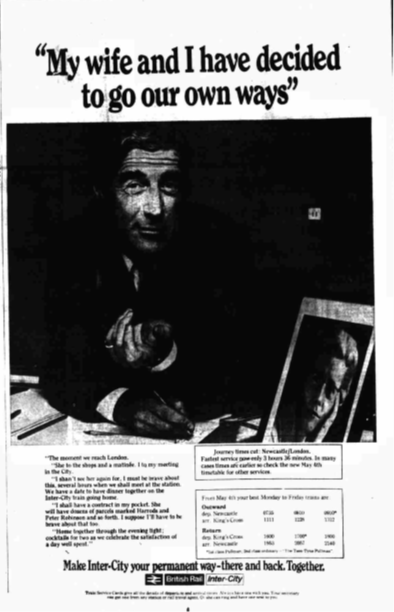

One gap was for the “Woman on her Own in London”, which noted a market of housewives who would accompany their husband on business trips and were “usually left on her own while he attends his conference, etc.” The advertisement described how the husband ‘had to be brave’ about his wife’s spending habits. What it revealed was a clear separation from masculine ‘work’ and feminine ‘shopping’, and worse still a separation between the ‘productive’ economy and the ‘consumptive’ economy.

British Rail Inter-City, ‘”My Wife and I Have Decided to Go Our Own Ways”‘, Newcastle Journal, (20 May 1970).

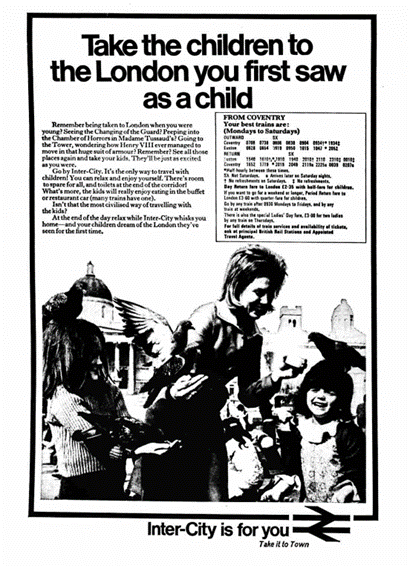

Secondly, the report highlighted the need for British Rail advertising to articulate a “sense of parental duty” as “a number of women felt they owed it to their children to show them the historical sites since this was of educational value”. This ultimately suggested that women were responsible for education and childcare in the family. This resulted in “Take the children to the London you first saw as a child”, which recanted the facilities on board the “civilised” railway travel, helping to facilitate this parental duty and make the most of time with children in London.

British Rail Inter-City, ‘Take the Children to the London You First Saw as a Child’, Coventry Evening Telegraph, (07 November 1972). 10.

These messages revealed extremely gendered economic roles deriving from the “Breadwinner” model that had persisted in the early 1950s – something which continued to persist in a number of nationalised industries.[4] These messages were captured under the tagline “Travel Inter-City Like the Men Do” in the mid 1970s, a tongue-in-cheek musical number about escaping the domestic chores.[5] Women in the advertisement sang:

Travel Inter-City like the men do,

Inter-City sitting pretty all the way,

So join us on the Inter-city when you feel you need a little holiday,

Away from the boring kitchen sink he needs you at,

We’re leaving behind the daily random common tasks,

C’mon and travel Inter-city like the men do,

We love a little outing now and then,

So up with women’s rights,

Come up and see the sights,

We’ll be nice and bright and ready for the men,

Away from it all and home again.

Whilst clearly made to be tongue-in-cheek, it reinforced stereotypes about work and travel. They placed childcare and homemaking at the centre of their message to Housewife’s, building a marketing message that assumed Women needed travel choices with these issues in mind. Innovation in British Rail’s marketing, which included extensive and advanced market research, had offered conclusions that helped reinforce ideas about gender and work.

Reflections on Data, Market Research and History

Travelling Inter-City ‘like the men do’ reveals just how important it is to understand data categories and how they reflect (or indeed, do not reflect) the society at the time. In the case of British Rail, its marketing captured traditional assessments of market research that helped to construct and reinforce ideas of an economy based on gender. For British Rail, the campaign was very successful in increasing awareness of rail services across the UK and demonstrated the versatility of a nationalised industry advertising services. However, in identifying the market in the way it did, it framed

Ultimately, Behind each dataset, definition or designation, there is always a broader social, cultural and political story that is not collected. The Census and British Rail examples show how data is an inherently interdisciplinary resource – it’s just about finding where the stories are, and how they relate to each other.

This is content from a future piece of research called “Travel Inter-City Like the Men Do: British Rail Marketing, Economy and Gender 1964-1979” due for release 2023.

[1] Sean Nixon, ‘Mrs. Housewife and the Ad Men: Advertising, Market Research, and Mass Consumption in Postwar Britain’, in The Rise of Marketing and Market Research, (Springer, 2012), pp. 193-213. 193.

[2] Prestidge, Jessica. “Housewives having a go: Margaret Thatcher, Mary Whitehouse and the appeal of the Right Wing Woman in late twentieth-century Britain.” Women’s History Review 28.2 (2019): 277-296.

[3] Ann Oakley, Housewife, (Allan Lane, 1974).

[4] Gareth Millward, Sick Note: A History of the British Welfare State (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).

[5] History of Advertising Trust. British Rail Inter-City, ‘Inter-City Commercial: ‘Housewives Day Out”, (1972). https://www.hatads.org.uk/catalogue/record/21a73039-e4f8-4e34-ad57-ab217e540555

About the Author

Dr Lewis Smith is a Senior Research Officer at the Essex Business School. He is currently working as part of a project to evaluate Eastlight Community Homes’ “All-In” community empowerment program. He is also interested in business and marketing in post-war Britain, in particular how nationalised industries communicated a rhetoric of public service and national interest.

Find Lewis on Orchid/LinkedIn/Twitter/ResearchGate