We’re approaching the release of 2021 census data for England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The UK Data Service also provides access to the previous UK censuses, back to 1971. In our ongoing census series, Dave Rawnsley explores how question design and definitions give a unique picture of the changing social and geographic nature of the UK’s population across the past fifty years.

We’re approaching the release of 2021 census data for England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The UK Data Service also provides access to the previous UK censuses, back to 1971. In our ongoing census series, Dave Rawnsley explores how question design and definitions give a unique picture of the changing social and geographic nature of the UK’s population across the past fifty years.

The UK Census remains the single most comprehensive source of data on the UK population. It provides detailed insight into demographic and socio-economic population characteristics, from household formations, journeys to work, detailed ethnicity, and so on.

The UK Data Service offers access to census aggregate data from 1971 to 2011, with data from the 2021 census being added soon after release this year. All the census datasets are open data, meaning that it’s free to access without registration.

Our Aggregate Data Unit is currently developing a new census data platform, which will offer users a more modern interface and increase the ease and speed of census data access. This work has involved huge efforts in migrating fifty years’ worth of census data.

As part of this work, we’ve been doing a deep dive into the data definitions, so we can be sure the information we make available is appropriately categorised and contextualised.

Every modern Census has come with a ‘Definitions’ volume to explain technical terms and show how questions on the census form translate into outputs in the census data.

Here are just a few examples we’ve discovered of how census definitions and concepts have changed since the 1971 census.

1971: The Housewife

Even though there was no specific question asked to identify the role of a ‘housewife’ in the 1971 Census, rules were created to try to identify which member of the family occupied the role, which you can see in the 1971 Definitions:

Figure 1: Definition of ‘housewife’ in 1971 Census.

Accessible version of the text in this image.

This definition says a lot about the traditional family, and the social construction of the family household, in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

That the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS, the forerunner of the current Office for National Statistics – ONS) felt the role should be identified and reported indicates the importance of domestic duty and identity at the time.

It is also interesting to see that the above rules were developed in association with a number of advertising/market research groups Were they perhaps keen to identify markets for washing up powder, groceries or floor cleaner?

There is a set of assumptions here about gender politics, which are no longer explored in the census. This is a good example of how the census must carefully balance continuity and change, as Professor David Martin explored earlier this week.

No two censuses are the same – the questions asked, and the definitions/concepts explored, reflect the social values and attitudes of the time, and as these change, census questions, definitions, and concepts are adapted and updated.

With this example, as the concept of family altered, the role of the ‘housewife’ was dropped from the census. It doesn’t appear in the Census Definitions from 1981 onwards.

Other changes in the development concept of family will become apparent in later censuses as single-parent families and LGBTQ+ families grew more visible and recognised.

1971: The end of the historical counties

Between 1973 and 1975, there was a huge shakeup in the administrative geography of the UK, with many of the old administrative counties done away with and replaced with larger ‘shire’ and ‘metropolitan’ counties.

The 1971 Census was therefore the last to include mention of the following counties:

- England – Westmorland, Huntingdonshire, Cumberland

- Scotland – Caithness, Nairnshire, Kincardineshire, Zetland

- Wales – Flintshire, Merionethshire, Radnorshire, Monmouthshire

These counties offer a snapshot of time gone by, and provide a wealth of historical information not only about the administrative geography of the UK, but also the culture and identity of local communities that stretches right back to the Normans, Anglo-Saxons, and Celts.

Zetland was the old pronunciation of Shetland, it is thought the derivation is from the Old Norse for hill-land or that the first syllable is derived from the name of an ancient Celtic tribe.

Merionethshire or Sir Feirionnydd supposedly took its name from Meirion, a warrior prince of the 5th Century.

Westmorland or Westmōringaland is the Anglo-Saxon land west of the moors. In England, shires had been created by the Kingdom of Wessex to control their land and then spread to the rest of England following Wessex’s political and military dominance.

The first shires of Scotland were created in Anglo-Saxon settled areas in Lothian and the Borders, King David I of Scotland created shires across his kingdom in the ninth century.

The name “county” was introduced by the Normans, and was derived from a Norman term for an area administered by a Comte or Count. Norman counties were simply the Anglo-Saxon shires, however, and generally kept the same names and borders though some small shires such as Hallamshire and Cravenshire were amalgamated into Yorkshire.

View a more detailed map of the pre-1974 counties.

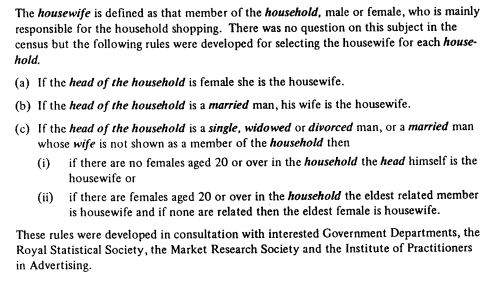

1981: Gaelic Speakers

In the 1981 Definitions, there is a very small piece of text that might almost be missed, which speaks volumes about a world that was perhaps coming to an end:

Figure 2: Information on the definition of Scottish Gaelic in the 1981 Census.

Accessible version of the text in this image

In 1981, the question on whether people could speak Gaelic was still asked in Scotland, but individuals were no longer asked if they could also speak English.

This was because the numbers returned in the 1971 Census were so low for Gaelic-only speakers that they would have been disclosive, meaning that there was a risk of individuals being identified from their responses.

What we can see here is, not a death of the Gaelic language itself, but an end to those communities who only ever spoke Gaelic and who never wanted or needed to learn English.

With the recent resurgence in use of the Gaelic language perhaps in the future we will see the questions asked once more.

1981: The Rise of Computers

Hidden away in the 1981 definitions is the following:

Figure 3: paragraph describing computer identification of family relationships

Accessible version of the text in this image

What had previously been done by hand was now in the hands of a computer? Progress, change…where will it all end?

1991: The End of Social Class?

Since the 1911 Census, it was customary to arrange the large number of groups in the ‘classification of occupations’ into a smaller number of summary categories called Social Classes.

What you did as an occupation had an impact on how you were viewed in society.

Just prior to the 1991 Census, we can see the first beginnings of a change to that idea:

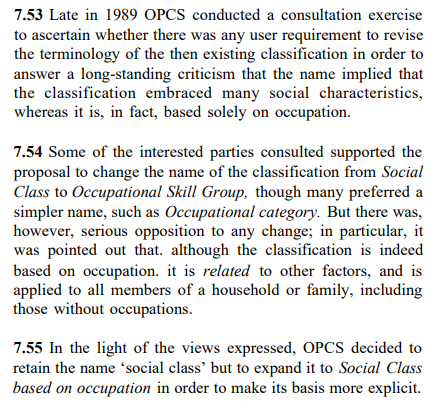

Figure 4: Information on changes to occupational classification in the 1991 Census.

Accessible version of the text in this image.

OPCS was the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, the government body that carried out the census – part of what would later become the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The Social Classes were not Upper, Middle and Working, but categorised, for instance, as “I – Professional” or “IV – Partly skilled occupations”. The feeling here was not that social class had had its day, but that one’s social class was not solely based on the job you did.

For example, a Lord of the Realm could put their occupation down as farmer, or a child from the East End could raise themselves to be a Lawyer, but neither would automatically change their social standing.

In 1994 the OPCS commissioned the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) to undertake a review of government social classifications.

As a result of the review, the ESRC recommended that a new Socio-Economic Classification, the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) replace both Social Class and Socio-Economic Group.

The final phase of the review involved rebasing the NS‑SEC on the new Standard Occupational Classification 2000 (SOC2000) published in June of that year.

Since 2001, the NS-SEC has been available for use in all official statistics and surveys. More recently, as a result of an EU Sixth Framework Programme project co-ordinated by ONS, a similar classification to NS-SEC has been produced for comparative European research, the European Socio-economic Classification (ESeC).

While these are just a few examples of societal and geographical change across the last fifty years, there are likely to be many more. As well as being an essential ‘snapshot’ of the population at any one time, the UK censuses form an increasingly important longitudinal study.

About the author

Dave Rawnsley is Senior Technical Co-ordinator for the UK Data Service. He leads the UK Data Service Aggregate Data Unit, based at Jisc.