People in higher professional and managerial occupations tend to command large incomes, exercise substantial power in their workplaces and pass significant advantages on to their children.

Daniel Laurison, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Swarthmore College and Sam Friedman, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, LSE assert that class analysis needs an approach which registers class destinations more effectively.

What is the relative exclusivity of different high-status professions in the UK?

Daniel and Sam’s research focuses on the many ways in which privilege affects career outcomes and finds that the upwardly mobile face a powerful and previously unrecognised ‘class pay gap’ within the UK’s elite occupations.

They identify the channels through which class inequalities are reproduced and define steps to support meaningful change.

The Data

Drawing on data from the ONS Labour Force Survey (LFS), the UK’s largest employment survey, Daniel and Sam demonstrate that a powerful ‘class pay gap’ exists in the UK’s elite occupations and in ‘the professions’ more broadly. They identified the LFS as a “gold standard, nationally representative source” upon which to draw.

Their analysis of the LFS provides the first large-scale and representative study of social mobility into and within the UK’s higher professional and managerial occupations.

The LFS is a random sample, nationally representative survey; it contains detailed and accurate measures of individual earnings and employment context; and significantly for the researchers, it includes variables that enabled analysis of three key areas considered to affect earnings:

- measures of educational attainment, and specifically whether a respondent has attended university

- both educational attainment and other key human capital measures such as job tenure, job training and health

- measures of an individual’s work context that are known to be associated with distinct occupational advantages, such as working in London, in large firms and in the private versus public sector.

The data contain large sample sizes and detailed social origin data, providing an unprecedented opportunity to understand the relative exclusivity of different high-status professions in the UK.

Specifically, the researchers linked the data from July 2013 through to July 2016, giving access to over 18,000 people working in elite jobs and offering an unprecedented opportunity to shine a light on the openness of the upper echelons of British society. Their aim was to understand whether mobility is more common into some sectors or occupations than others.

The findings

Drawing on the addition of the socio-economic background variable to the LFS in 2014 about the job of the main income-earning parent when a subject was 14, the researchers examined mobility inflow rates among higher professional and managerial occupations.

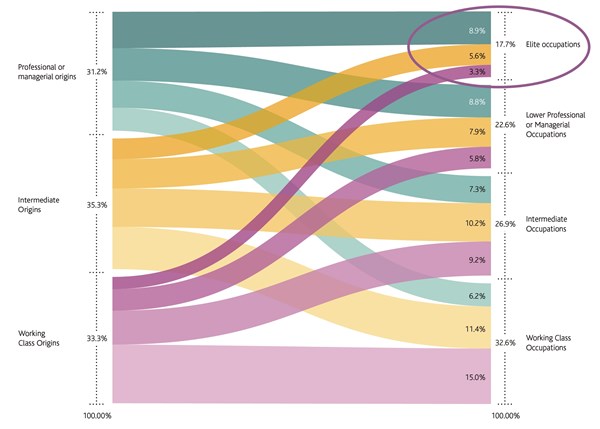

The flows from left to right represent people from each class origin who moved into each class destination and the thickness of each line shows the proportion who take each possible path:

Daniel and Sam found that in higher managerial and professional occupations, people from privileged backgrounds in elite occupations earn on average 16% more than colleagues from working-class backgrounds. Significantly, they found that this gap persists even when comparing individuals who have the same educational attainment, occupational role and level of experience.

They then interviewed employees from different backgrounds at different grades to understand the class pay gap in four professions:

- Multinational accountancy firm

- Television broadcaster

- Architecture firm

- Self-employed actors

They found that people from working class backgrounds drop off sharply as grades increase, noting a vertical sorting into a ceiling effect, excepting in architecture, noting four main drivers:

- Financial safety net bank of mum and dad

- Enables more risk-taking in their career

- Filtering out of the most competitive areas of professions for more stable but less lucrative roles

- Sponsorships operating beneath formal process in a form of patronage

The impact

Daniel and Sam conclude by proposing ten policy recommendations to address the class ceiling in the UK’s elite professions. Their research is being used to inform the work of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Mobility: https://www.suttontrust.com/policy/all-party-parliamentary-group-on-social-mobility/

The Class Ceiling project proposes a fundamentally new way of conducting social mobility research. While ‘fair access’ to elite occupations is invariably presented as the most important indicator of a just society, this presentation masks a much longer shadow which class origins cast on occupational trajectories.

By uncovering and exploring these hidden barriers, the project not only aids understanding of how class inequalities are reproduced but also aims to inform policy initiatives aimed at breaking down elitism and encouraging true equality of opportunity.

“By shedding light on the ways in which merit is at best an insufficient explanation for career success at the top, it will be possible to raise wider questions about the legitimacy of an economic system that too often allocates profoundly unequal rewards based on the accident of social origin.”

Sam Friedman

Read the Impact Case Study

https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/the-class-ceiling

Find out more about the Labour Force Survey