![]()

Christina Giasemidis, winner of the UK Data Service’s dissertation award, introduces the Women’s Perceived Safety at Night Index.

Christina Giasemidis, winner of the UK Data Service’s dissertation award, introduces the Women’s Perceived Safety at Night Index.

The urban night is a landscape of excitement for many, but it can present an overwhelming apprehension for others. The difference is inherently gendered.

Since the first ‘Reclaim The Night’ march in 1977, in response to curfews placed on women in Leeds while the Yorkshire Ripper was active in the area, women have fought to claim their space in the urban night. Forty-eight years later, the fight continues.

In the UK, women feel less safe in all settings in the dark compared to men. Perceptions of safety at night are highly personal, but could secondary data help identify ways to improve these perceptions?

A feminist vision for the urban landscape

For my undergraduate dissertation, I wanted to explore how a city could become more ‘feminist’. I became interested in this after reading the book Feminist City by Leslie Kern and following the fantastic work led by Councillor Holly Bruce in Glasgow to become the UK’s first ‘feminist city‘.

In my view, the path towards a feminist city must begin with exploring the difference in men’s and women’s perceptions of safety in the city – a gap most pronounced at night.

This leads me to my research, which explored the use of secondary quantitative data to measure women’s perceptions of safety at night across a city’s neighbourhoods. My city of choice? As the birthplace of the ‘Reclaim The Night’ marches, it had to be Leeds.

After reviewing existing research to identify the most significant factors that influence women’s perceptions of safety at night, I created a composite index by compiling several data sources. These included:

- Land use density

- ‘Eyes on the street’

- Area condition

- Street lighting

These datasets underwent pre-processing and were standardised before being combined to reveal a final score for each neighbourhood. This resulted in a ranking of Leeds neighbourhoods, from those perceived as most safe to least safe for women at night.

Challenges

This method appeared to be the most sensible way to measure women’s perceived safety on a large, city-wide scale. However, I was surprised to find how little empirical research on women’s safety had been conducted this way.

Part of the problem is a lack of widely available, relevant secondary datasets, but some argue that it is simply impossible to measure a perception quantitatively. These limitations have resulted in a history of small-scale studies using interviews, which cannot encompass an entire city of women’s experiences of the night.

I was determined to attempt a new method of measurement that could cover a larger scale while identifying the perceived safety of smaller neighbourhoods.

Because nothing can change if we can’t pinpoint the places needing intervention.

Hence, the selected datasets were city-wide but were at a neighbourhood-level geography. These included various land use type data, streetlight counts, Index of Multiple Deprivation scores, venues participating in Ask for Angela, and distinct footpaths. These factors were selected based on availability, geography and ability to measure women’s perceived safety at night.

In my search, there were datasets I would have liked to use but were behind a paywall or covered too large a geography for my study. This illustrates the importance of open-source data and supports the idea that limited data availability creates a challenge for quantitative researchers in this field.

The Women’s Perceived Safety at Night Index

The finalised index, the Women’s Perceived Safety at Night Index (WPSNI), categorised neighbourhoods in Leeds on a very high to very low perceived safety scale.

![]()

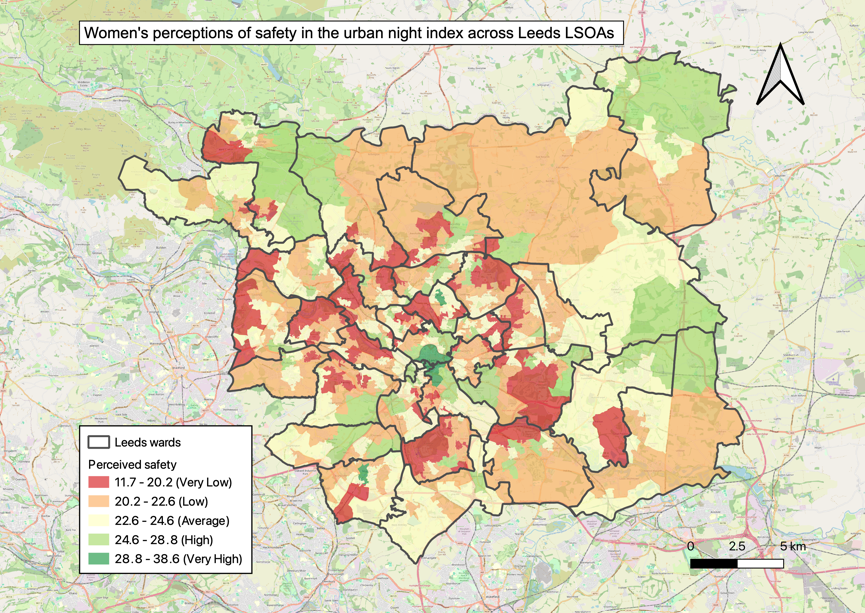

Figure 1: Women’s perceptions of safety using the urban night index across Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs).

Click here or on the image for a larger version.

The scored and ranked neighbourhoods were then visualised using GIS, as shown in the map above.

This map illustrates that the perceived safety in town and city centre neighbourhoods is very high, as the most significant area categorised this way highlights the city centre of Leeds. Meanwhile, the areas with very low perceived safety correspond to more open and green areas (e.g. parks). This suggests that women feel safer on busy, active streets instead of quiet, potentially dark places.

To validate these results, I published a survey to be completed by anyone who identified as a woman and had lived in a smaller section of the study area in the last five years.

The survey results illustrated a very mixed bag. A higher percentage of respondents agreed or strongly agreed (51.2%) that the mapped index was accurate to their experiences, but a significant proportion disagreed or strongly disagreed (41.2%) that this was true.

Although I personally feel safer at night in busier areas, other women felt more apprehension in these areas due to a higher likelihood of drunken and anti-social behaviour. Behaviour more likely to be associated with men who statistically pose significant threats to women.

Room for improvement

The research results indicated that quantitative methods can be used to measure women’s perceptions of safety in the urban night on a large scale; however, the measure is not guaranteed to be accurate for all women’s experiences. Ultimately, a mixed-methods approach is more appropriate.

A more targeted and widespread survey could help solve this issue. However, this relies on the willingness of councils and governing bodies to fund research of this kind. While many cities in the UK have announced strategies to improve women’s safety, a study of this kind has not been conducted by any local authority.

Fine-tuning my method could significantly impact women’s safety strategies in the future if taken on board by bodies with more resources.

A look to the future

The results of this research have implications for local and national urban design and planning policy as they highlight the individualistic nature of women’s perceived safety. A design that works for one woman will not necessarily work for another. This must be understood to move toward a gender-equal urban experience.

An accurate index of this kind could assist councils in implementing safety strategies.

For instance, the index identified large green space areas as priorities for intervention.

The highest likelihood of accurate intervention is through a mixed-methods approach that can capture the nuance of women’s safety perceptions.

I hope the publicity gained from my dissertation winning the UK Data Service Dissertation Award 2025 will inspire policymakers to attempt this method for their local areas.

Perhaps then, women could Reclaim The Night.

About the author

Christina Giasemidis is an MSc Urban Design and International Planning student at the University of Manchester.

She has a keen interest in urban and feminist geography and plans to take these interests into an urban design and planning career.

Christina was awarded the UK Data Service Dissertation Award 2025 for her BA Geography with Quantitative Methods dissertation completed at the University of Leeds.

Follow Christina on LinkedIn.

Other stories you’ll find interesting

Comment or question about this blog post?

Please email us!