Dr Andrew McNeil and Dr Elizabeth Simon discuss their research on Euroscepticism and how studying at university impacts this in the UK.

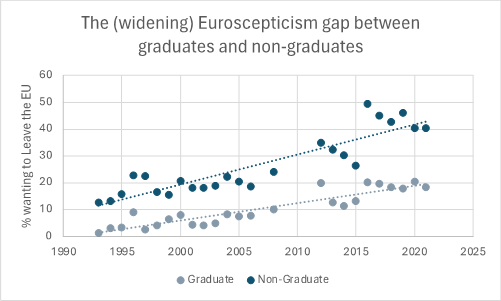

The importance of education in shaping British public opinion came to the forefront of debate in the wake of the 2016 EU referendum, when it became evident that while approximately 70% of those with university degrees had voted to Remain, just over 30% of those with at most secondary school qualifications had done the same. Yet this educational divide over Euroscepticism is not new. Data from the British Social Attitudes survey shows that graduates have been considerably more favourable towards European integration than their non-graduate counterparts since the early 1990s, though the ‘educational gap’ in these attitudes has widened over time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 – The (widening) Euroscepticism gap between graduates and non-graduates

With increasing attention being paid to the fact that university graduates tend to be more pro-Europe than non-graduates in recent years, it is unsurprising that people have begun to speculate about whether there may be something about the experience of studying at university that causes attitudinal change. Indeed, there are good reasons to think that this might be the case. We know that attitudes are formed through socialisation experiences. University campuses are not only sites of formal classroom-based learning, where students learn about the social and political world, but are places where new friendships are formed, networks are developed, and where attendance can often mean less time spent with family and friends – who might have informed early attitudes. We also know that our attitudes tend to be more malleable in the ‘impressionable years’ between ages 17-25, the period in which many will commence their undergraduate studies.

Our new study, published in the European Journal of Political Research, seeks to shed light on this. It asks: does studying at university cause us to become less Eurosceptic? Or does it simply appear this way because graduates are a highly selected group who tend to have different pre-adult experiences, and occupy different adult status environments, than non-graduates? We know that the kinds of individuals who tend to enrol at university differ from those who do not in important ways, and that studying at university tends to ‘open doors’ for graduates – granting them access to opportunities that their non-graduate counterparts may not have access to. So, it may be these selection-into-education and post-educational sorting effects – also referred to as ‘allocative’ effects – that shape attitudes, rather than any ‘direct’ causal effect of university study e.g., the socialisation experiences individuals are exposed to on university campuses.

We also explore whether the effect of university study on attitudes toward European integration is more substantial for those who graduate at younger ages, as we would predict under the ‘impressionable years’ hypothesis.

We use data from the British Household Panel Study and UK Household Longitudinal Study (Understanding Society), collected in the period 1992-2022, and two different methods, to provide estimates of the average causal effect of university study on Euroscepticism in the modern British context, and how this varies by age at graduation. Our first method considers how much the same individuals’ attitudes toward Europe change over the panel period and considers whether the average level of attitudinal change observed differs for those who have obtained a degree in that time, as compared to for those who have never studied at university. The second method explores how attitudes toward European integration vary between siblings who have and have not studied at university in the period and is based on the assumption that co-resident siblings will have had almost identical pre-adult socialisation experiences.

Our data confirms two findings from previous literature and most people’s intuition. 1) Graduates are, on average, less Eurosceptic than non-graduates. 2) Before going to university, future graduates are already less Eurosceptic, on average, than individuals who will never graduate. In other words, there is a selection effect. We can only speculate as to what may be driving this difference, existing theories include socio-economic background and career ambition, which may already drive attitudes towards European integration.

The novelty of our work, however, lies in considering whether any changes in Euroscepticism occur because of university study.

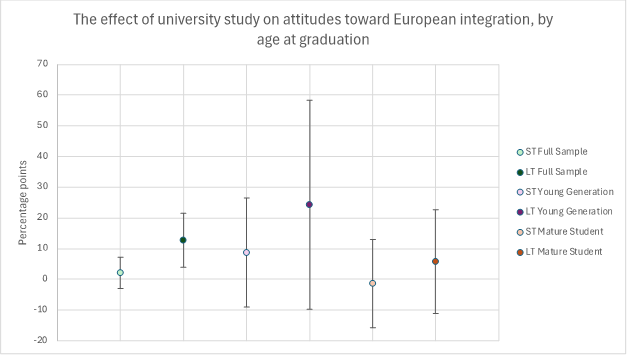

When we study the effects of studying at university over a relatively short time period, a maximum period of 7 years after our initial pre-university observation, there is only a substantively small (and non-statistically significant) reduction in Euroscepticism. Here, we measure ‘reduction in Euroscepticism’ relative to non-graduates, or in our second set of models for graduates relative to their non-graduate siblings. However, over a longer period, at the extreme more than 20 years after the initial observation, the reduction in Euroscepticism for graduates relative to non-graduates is both large and statistically significant (see Figure 2, where we report estimates from our first methodology only).

Figure 2 – The effect of university study on attitudes toward European integration, by age at graduation

Notes: ST=short-term; LT=long-term.

These findings suggest that the substantively large effects of university on Euroscepticism only become apparent over the long-term. One explanation is that the direct effects of university study, from peers, classroom learning, and so on, only manifest later in life – an explanation which we find unlikely. More plausible, in our view, is that being a graduate increases pathways into jobs with better pay and more autonomy, social networks with other graduates, and living in thriving areas. These are all factors that are predictive of less Eurosceptic attitudes.

When splitting our analysis by generations, we find evidence that there is a larger ‘university effect’ for those who study when young relative to those who do so as mature students – both in terms of the short-term, ‘direct’ effect, and long-term ‘allocative’ effects. This finding is consistent with the ‘impressionable years’ hypothesis and our ‘allocative’ effects explanation, as younger individuals are less likely to already have stable partners, strong ties to an area, and to have established careers, so university attendance has more scope to shape their adult trajectories and thus their attitudes toward Europe.

To summarise, our study shows that graduating from university has a substantively large effect in reducing Eurosceptic attitudes, on average, and that it appears to do so predominantly because of the opportunities gaining a degree affords rather than due to ‘direct’ experiences of on-campus socialisation.

An important avenue for future research will be using longitudinal data sources – like the British Household Panel Study and UK Household Longitudinal Study – to identify precisely which post-university adult-status experiences appear to be driving the stark educational divide in attitudes towards Europe which has emerged in Britain, and beyond.

About the authors

Dr Andrew McNeil is a Research Fellow at the Political Science Department, University College London. He is currently working on the Mental Models of Political Economy (MENMOPE) project. Andrew’s research interests include the political consequences of inequality, particularly social mobility, British politics, and the political feasibility of the green transition.

Dr Elizabeth Simon is a Postdoctoral Researcher in British Politics, based in the Mile End Institute and QMUL’s School of Politics and International Relations. Her research interests extend broadly across the topics of attitudinal formation, political behaviour, inequalities and identities and working on public policy projects.