Stuart Mills continues his series on data policy theory, exploring data as a resource and how it is shared or traded.

Stuart Mills continues his series on data policy theory, exploring data as a resource and how it is shared or traded.

Who decides who decides?

Data are limitless, both from a philosophical perspective (we can always make more decisions about what to observed and record, and what to do with those records) and a material perspective (data can be reproduced at almost no cost, be it users giving over their personal details, or a computer duplicating files). Yet data also seem to produce a tremendous amount of economic value, primarily in the form of targeted advertising (though this rationale is increasingly being challenged, with a nice summary given by Jesse Frederik and Maurits Martijn).

Previously, I argued this apparent paradox was solved by the apparent closing off of what we might call ‘common data’ from the public, with data (and the means of collecting data) residing in private hands. Academics Jose van Dijck, Frank Pasquale and Lizzie O’Shea have made similar arguments.

The Laissez Faire model of data ownership is one way of organising what academic Nick Srnicek calls platform capitalism.

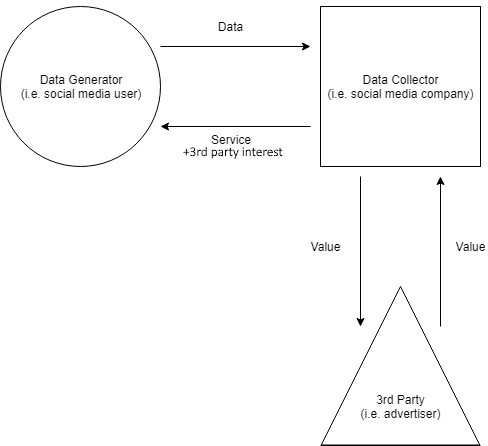

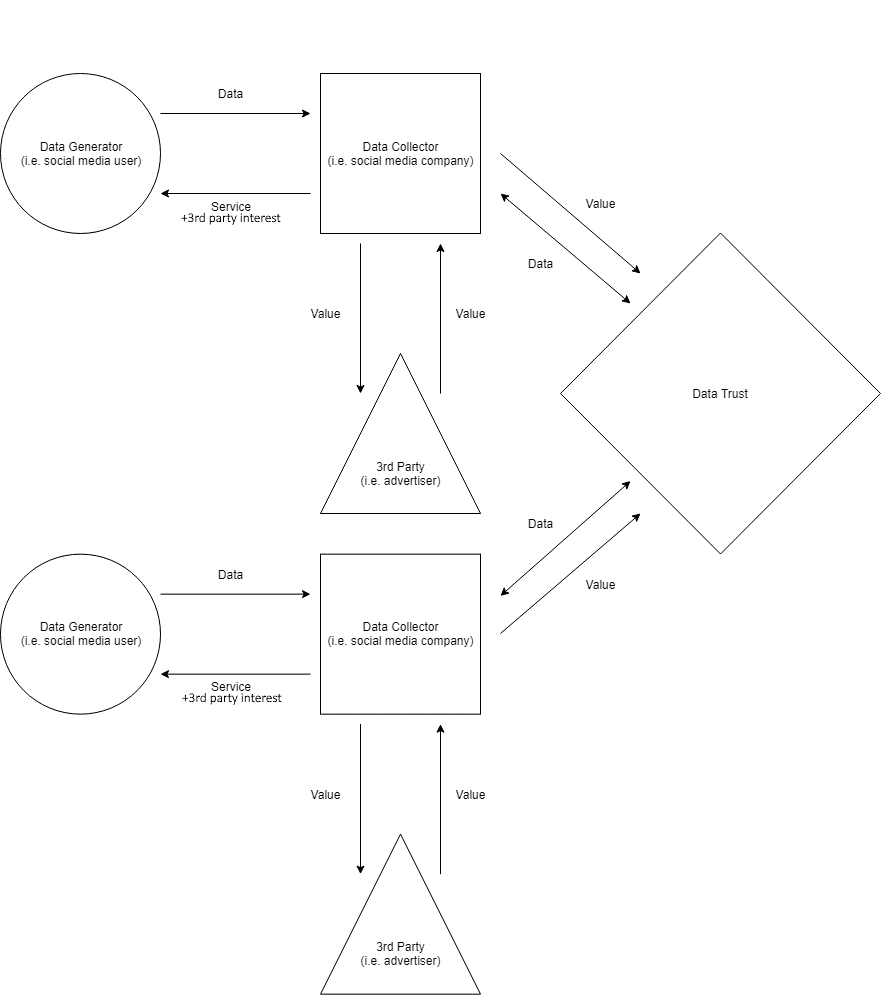

Figure 1: Data Flows in a Laissez Faire Data Ownership Model

In this simple model, taken from my working paper on data ownership, data collectors perform the same role as platforms do for Srnicek, acting as intermediaries between users and third-parties, controlling the flow of data (which is to say, accumulating data and controlling access), and extracting value from their position in the data flow.

However, we could organise this flow and these actors differently.

For instance, we might accept the transactional theory of data (users receive services in exchange for their data in a form of transaction) but accept – much in the way trade unions do – that there is an imbalance of power between the individual user and the service.

A single user cannot negotiate with Facebook over how their personal data is used – Facebook may provide the user with a range of options they can opt in or out of, and may allow the user the freedom to provide more or less information about themselves, but individual users have almost no power to influence what is and isn’t up for negotiation; as academic Shoshana Zuboff writes, “who decides, and who decides who decides.”

In recent years, the idea of collectivisation on platforms in the form of data trusts has emerged. For instance, we might imagine something like a data-centric data trust.

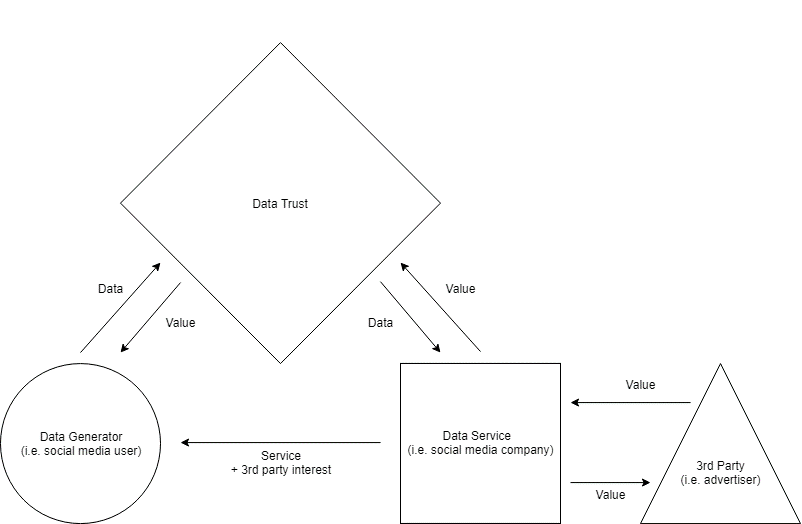

Figure 2: A Data-Centric Data Trust

Under this model, users do not individually provide data to a data service (platform), but instead collate their data into a large dataset independent of the data service called a data trust.

The trust – again, in much the way trade unions operate – then negotiates access rights with the data service in exchange for additional value which the trust then distributes to users. Value is an ambiguous term – it could be financial, or it could be additional user rights such as negotiated opt-outs, advertising bans or privacy rights.

While some, such as the Open Data Institute (ODI), have characterised this model of data trust as a data union, I have argued that – from a practical, as well as political economy perspective – this model is a data trust, merely a variation on an alternative model which I will discuss shortly.

But, why data-centric? It’s quite easy to forget that behind datasets are people, and so some clarity here is important.

It seems reasonable, as least theoretically, to conceive of a data trust that governs access to data, and a data trust that governs access to those from whom data is collected. The latter is another model we could consider: the generator (user) centric data trust.

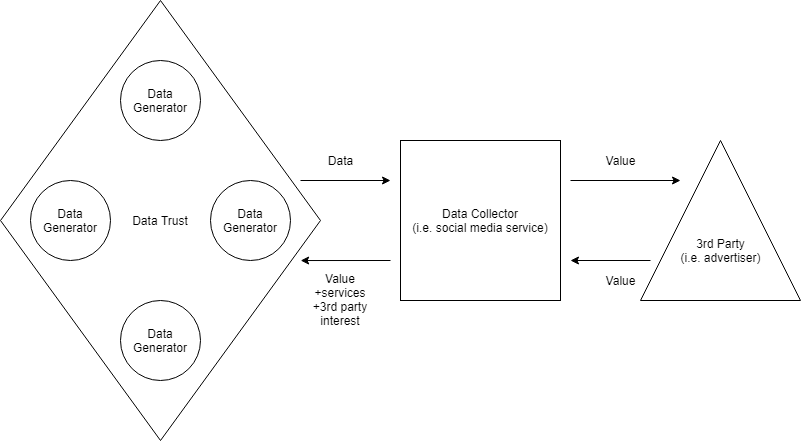

Figure 3: A Generator-Centric Data Trust

In this model, the trust itself negotiates the terms on which individual users within the trust interact with the data collector (platform).

Thus, we have still not entirely abandoned the transactional theory of data, but the imbalance of power between user and platform has been reduced because users operate with a degree of solidarity with fellow users. In this sense, the generator-centric data trust emerges more as a sociological idea than a political economy or even technical one.

For example, the #DeleteFacebook movement following the Cambridge Analytica data scandal may, in time, come to serve as an example of a proto-generator-centric data trust: users felt Facebook had violated some social (media) contract, and responded with a call to boycott.

Data as a Common Resource

So far, with data trusts, we can begin to see that as we relax the transactional idea of data, we can begin to build new ways of organising data ownership, data flows, and value flows.

To an extent, the functionality of a data common precedes any philosophy or political economy we might want to have.

Functionally, a data common is the idea that only one copy of a user’s data need exist, that this copy should be stored within the common, and that the user should be able to grant and withdraw access to other entities (be them users or platforms) whenever they desire.

In talking about data commons, the language is less about data as a common resource (though it may be), and more about interoperability in the language of academic Robert Grossman (and candidate for the democratic nomination for president Andrew Yang), or “digital citizen accounts” in the language of Mathew Lawrence and Laurie Laybourn-Langton of the think tank IPPR. In this sense, a data common may even double down on the idea of data as property, or at least something that can be owned (Yang even says as much).

The problem with these descriptions of data commons is they don’t really distinguish a common from some of the data trusts already discussed.

For instance, the data-centric data trust would function very similarly to a data common prioritising interoperability. This is not to say these conversations are not bringing new ideas to the table; the data commons discussion is very much in its infancy, and often the applied brains of policymakers and think tanks are racing ahead of academics such as myself who find tremendous comfort in definitions.

But I do want to draw some difference, and so I will examine a specific type of data common.

Fundamentally, talk of commons and trusts is talk of how we can change the ownership structures surrounding data. For legal scholar Lothar Determann, the limitless nature of data means no one can own data, retracing an economic argument that ownership is only necessary because of scarcity. If we’re willing to reimagine how data could be owned, we might also consider data a common resource owned by no one.

This is the position of academic Ernst Hafen, and – I suggest for this specific conversation – a good departure point between a data trust and a data common. Hafen’s model supposes each individual be afforded a new right, the so-called right to a copy (which is already enshrined in GDPR).

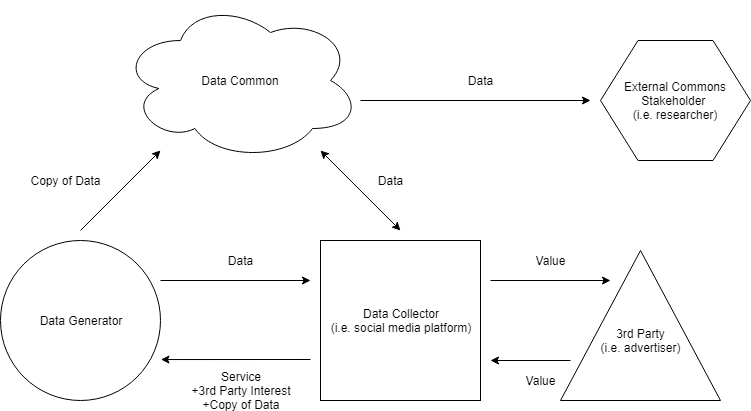

Figure 4: A Data Common inspired by Hafen’s model

People would exercise this right regularly, uploading their copies to a central common. This common would be accessible by everyone, in turn eliminating monopoly control over data access, and allowing the economic value of data to fall to zero.

Hafen then supposes, as a result, that platforms would have to compete on their quality of service (whose platform hosts the best content?; who offers the most privacy?; who prioritises convenience?) rather than rent-seeking via their data monopoly.

This is quite a radical idea, and would be met with many obstacles, chiefly privacy concerns.

So much of our current discussion about data and platforms stems from the violation of data privacy, and this data common would seem to do little to ameliorate those concerns. Individuals would demand privacy (and it is afforded by the UN as a human right), and so adjustments would have to be made. Some ideas include the use of blockchain and decentralisation; extending the right to a copy to include a right to data anonymity; and the use of gatekeeping.

For example, I have proposed – counter to Karen Yeung’s idea of collective privacy – the concept of collective transparency: only those who contribute their data to the common may extract data from the common. This, of course, is a flawed idea (data can be easily copied and disseminated, for example), but it is this sort of thinking which a radical data common demands.

The Tech Company Strikes Back

There remains a data trust which I haven’t discussed.

While the data trusts and data commons I have discussed have sort to replace the laissez faire model of data ownership, what I called the collector-centric data trust (which is the most commonly discussed type of data trust) sits alongside the laissez faire model and – I suggest – actually responds to the problems generated by laissez faire.

Figure 5: The Collector-centric Data Trust

If this trust looks somewhat familiar, that shouldn’t be surprising. The collector-centric trust simply adapts the model I suggested for the laissez faire model by incorporating a data trust which data collectors contribute to and benefit from.

Under this model, the transactional theory still applies, but data collectors coordinate their resources to construct a data trust (or monopoly) which only trustees have access to. One can imagine that such a model would allow data collectors such as tech companies to reduce the costs of collecting data while benefiting from access to huge amounts of data by each collector specialising in the collection of different information.

For instance, one collector might collect health data, while another might collect financial data, and both collectors benefit through the sharing of this data.

However, it seems one doesn’t really need to imagine.

While not strictly called data trusts, academic Jonas Andersson Schwarz’s concept of the superplatform seems to resemble a collector-centric data trust, at least in principle. A superplatform is a platform like Facebook or Google who provide functionality tools to smaller platforms, and in turn receive a copy of the data collected by these platforms.

For instance, many platforms while allow users to log in via their Facebook accounts (Instagram) or Google account (YouTube). These smaller platforms perform the imagined role of specialised data collectors, while the superplatform collects and combines various specialised data to use for various purposes, often developing new services and improving algorithmic targeting.

To be sure, the superplatform isn’t a data trust, collector-centric is otherwise.

I am quite confident some working in the world of data trusts would have significant objections to my likening of one with the other.

For instance, collector-centric data trusts can be used to enable data sharing between healthcare trusts, improving patient outcomes, or between local businesses, allowing communities to benefit from and innovate with their local data. But as Srnicek argues, the tendency for platforms in the digital economy is towards consolidation of data resources, and so it would equally be a mistake to discuss data trusts without considering how these ideas may develop and evolve.

As a concluding statement, I do not believe any model is necessarily superior to another. All have advantages, and all would/do create significant economic and social challenges.

In my opinion, the benefit of these models is not in choosing one and advocating for it, but in the realisation that by understanding the components, entities and actors that form the digital economy, we can re-arrange the digital economy to align with our objectives as a society.

About the author

Stuart Mills is a PhD researcher at the Manchester Metropolitan University Future Economies Research Centre. His research includes behavioural economics, behavioural public policy, hypernudging and data politics.