Heather Joshi, Alex Bryson, David Wilkinson and Kelly Ward from the Department of Social Sciences, Institute of Education, University College London consider the gender pay gap for people born in 1958 and the effects of unequal pay on financial equality.

Although Equal Pay has been in legal force since 1975, the gap between the pay of men and women in Britain is slow to close. As they move through adult life, men’s and women’s family responsibilities lead to a divergence in employment paths with consequences for their rates of pay. Unequal rates of pay along the way underpin gender inequality in lifetime income. If similarly qualified men and women receive different pay for the same work it is not only unlawful but unfair and inefficient.

Photo by Philip Veater on Unsplash

While over the years the national average pay gap has been shrinking, there are strong patterns by age. It is relatively small among people in their twenties and rises over the next two decades of age to reach a peak in the mid-forties, slackening off somewhat for workers in their fifties and sixties. This uphill stretch coincides with the years when people are having families, and many workers, women as well as men, have children at home.

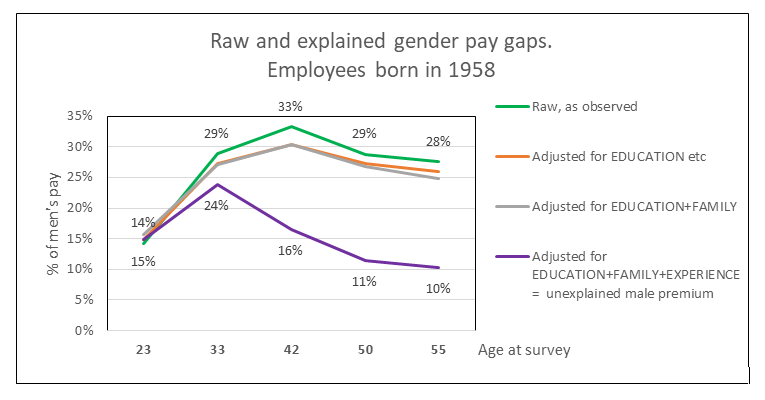

We investigate this pattern in survey data about people born in a week of 1958. They reached school leaving age the year before the Equal Pay Act came in. They have been followed to age 55 in 2013. As shown in the figure, the gender wage gap in hourly pay at 23 was 14% of men’s pay, rose to a peak of 33% at age 42 and dropped back to 28% most recently at age 55. The latter ratio is likely to be magnified in unequal pension entitlements. In contrast to the national averages, our survey data can disentangle how far gender differences in education, work experience, and family circumstances can account for this long-term profile. This exercise also identifies any otherwise unexplained unequal treatment of men and women in the labour market.

Differences in the educational attainments of men and women of this generation, though still favouring men, were relatively small, and accounted for only a minor part of the cohort’s pay gaps (see the small gap between the top two lines in the figure). The presence of partners and children in the home played even less of a role in the accounting for the gap (see the even smaller gap between the second and third lines plotted in the figure). It was differences in work experience which accounted for a major part of the pay gap (see the widening area above the bottom line in the figure). The difference was particularly large for experience in full-time jobs. Although the women workers at later ages had substantial part-time experience behind them, it contributed little if anything to their rate of pay, thus it was women’s ‘failure’ to accumulate full-time experience that led to the widening in the gender wage gap after age 33.

The presence of family in the home is not so very different for male and female employees, but when it comes to remuneration, it is a different story: parenthood appears an asset for men but a liability for women. This a-symmetry contributes to the unexplained undercurrent of unequal pay for equally experienced and qualified workers in equivalent family circumstances. Described as the ‘unexplained male premium’, this is plotted as the lowest line in the figure. It peaked at 24% of men’s pay at age 33 and stood at 10% at age 55.

Although pay is particularly low for mothers in part-time work, we find that women full-timers, too, faced ‘unexplained’ pay gaps. We also find little explanation for the pay gap among workers who have not had children (8% at age 55). Therefore the pay gap is not all about children. Parenthood is not the sole source of the pay gap, there is an unexplained ‘premium’ among men who have not had children towards career end.

To conclude, a pay gap for men and women born in 1958 with equivalent attributes still remains ‘unexplained’. It affected women who didn’t have children as well as those who did. Looking forward, it means that there is not a level playing field on the pensions front, despite credits to the state pension for family responsibilities. Looking towards the following generations, where the division of productive and reproductive work between men and women is slowly becoming less rigid, unequal pay may still limit the extent of convergence. If men command higher rates of pay than women in the workplace, it will hamper gender equality in the home. For example unequal pay creates a disincentive to men to taking up their entitlement to parental leave, which in turn would reinforce the gender asymmetry of pay to parents.

Our evidence suggests that the Gender Pay Gap warrants the renewed attention of policy it is now receiving and further research investigation of the processes behind it.

Acknowledgments

This research is based on the National Child Development Study (NCDS) available from the UK Data Service. We are grateful to UCL for funding our exploratory research, to the Centre for Longitudinal Studies for help in preparing our data set, and to the members of the 1958 birth cohort for their long-term co-operation with the study.

About the authors

Heather Joshi CBE FBA was formerly Director of the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, and Professor of Economic Demography at the UCL- IOE. Her research is in an interdisciplinary area covering women’s role in the family and the economy, among other topics to which she has applied longitudinal evidence. She is the lead author of this blog, produced by a team of which Alex Bryson takes the main lead.

Alex is Professor of Quantitative Social Science at UCL’s Department of Social Science. His research spans labour economics, industrial relations and programme evaluation. He is a Research Fellow at IZA and NIESR where he was previously Head of the Employment Group. Prior to that he was Research Director at the Policy Studies Institute where he worked for nineteen years.

David Wilkinson is Principal Research Fellow in the same Department. His research focuses on the labour market, economics of education and policy evaluation. He is a Research Fellow at NIESR where he worked between 2006 and 2016.

Kelly Ward is now a PhD student in the Department, studying the impact of childbirth on maternal employment after an extensive background in longitudinal analysis and data management.