Bram Vanhoutte, UK Data Service Data Impact Fellow, explores the potentially negative side to the impact agenda.

As has been showcased on this blog, there is a lot to be said for research impact. It underlines that scientists, especially social scientists, naturally want their research to have an impact, to change the status quo.

One aspect that for me is as important as understanding how research can have impact, is knowing why you want to have an impact.

Do we strive for impact because it flows from the research we do, or is it because impact is becoming a measure of research performance?

The potentially negative sides of the impact agenda have been discussed less on these pages, which feels a bit like having an elephant in the room, as it is a common point of discussion among academics studying the topic (see for example digital sociologist Mark Carrigan ).

I want to stress that I think societal impact is a great thing and should be strived for by researchers, but am less sure about it as a measure of successful research, which is why I want to place some critical footnotes.

In terms of academic impact, publications are a leading measure of academic performance and scientific impact.

This has led to some questionable publishing strategies, such as for example reducing findings to the smallest publishable unit, co-authors being added to publications without having contributed substantially and p-hacking, or mining data for significant results before having a specific testable hypothesis to work from.

These perverse effects do not diminish the fact that scientific publications are still the main vehicle for presenting findings to the academic community, or carry personal importance in terms of academic achievement of publishing an article. In the same vein, the increased attention put on research impact can potentially alter the meaning of research impact.

I’m thinking specifically about the research impact and the role of a researcher, rather than society, stakeholders or individual participants in impact projects, as that is what I know best.

Although it is obviously makes enormous sense to connect with the publics we are studying, we should also not be afraid to question why this has become a part of the research evaluation framework (REF). The UK is the only country where research impact is an explicit criterion for research proposals and evaluations, while it is surely not the only country where science has an impact on society.

In other words, having impact as a research performance measure kind of changes the meaning of research impact from something you want to do to something you have to do.

What quality impact is, how it is measured and evaluated is left to us, but it needs to be done to be successful.

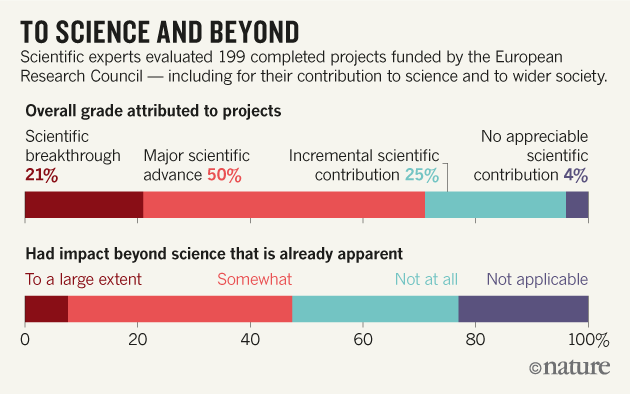

The European Research Council, which by definition only funds excellent research, recently investigated (retrospectively and independently of the researchers) the societal impact of its projects, many of them “blue sky” high risk projects.

While 10% had a large impact on society, a quarter were expected to do so in the near future. So of top research projects funded by the most competitive funder in Europe, only a substantial minority had (or will have) a big impact, while about half had some impact.

This makes me wonder if early career researchers are really the best people for this job.

Impact takes time, needs long-term commitments and ideally includes both policy people and stakeholders. I’m not sure that (young) researchers are the best-placed and most efficient use of resources to do this type of impact work.

Interest groups and NGO’s to some extent are already covering a lot of the interaction between policy and stakeholders, and have more experience and skills in bringing about evidence based policy change. Access to the right connections and social skills, not always a prerequisite for good research, are a necessity for good and high level impact work.

On the other hand, working on the ground, a lot of impact work is community work. While many social scientists are quite good in this, their engagement can only be temporal, and the funds to put long term solutions in place often have to be found elsewhere.

A second point is

Do early career academics have time for this job?

Next to:

- gold standard teaching,

- doing excellent four star research,

- writing award winning research proposals

- filling in numerous forms for administrative purposes,

you also should have a REF-able impact case study.

While there is a lot of flexibility in terms of how and when you work as an academic, these varied and, in a sense, never-ending job demands rarely result in a healthy work-life balance. Burnouts among young (and successful!) academics are commonplace, and knowing when to say no can be difficult in the beginning of an academic career.

By including research impact as an explicit need for excellent research and successful research projects, the workload is further increased.

The recent strikes of academics all over the country have exposed a number of related issues that highlight how the marketization of universities is threatening the quality of teaching. We should take care not making impact projects part of this market, with academics competing for access to stakeholders or participants, who might in the end feel tokenistic, in the sense that they are asked to participate to fulfill our demands, not theirs.

While for established academics having impact might not be such a big deal, as they already have the resources, know-how and networks to do so, the need to have an impact can be more of a struggle for early and mid-career academics.

Not only are many in a phase of their lives where families are formed at the same time that careers have to be made, it’s also a question of your priorities are as a young researcher to fulfill the many demands to make a career in science.

I believe that impact can be a part of that, but should not be a demand for everybody.

Some topics are harder to “impact” than others, and some people are better placed and better equipped to do impact work than others.

I stress again that I think impact is a good thing, and through social media opportunities for impact have multiplied exponentially – I do hope this blog counts as impact.

I just wonder about what the longer term selection effects of impact as a research performance measure will mean for research as a whole, and specifically for the careers of young researchers.

About the author

Bram Vanhoutte, @bvhoutte, is one of the UK Data Service Data Impact Fellows. Bram is a Research Fellow in Sociology at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at The University of Manchester. The main focus of his research is the different ways in which people age, and in particular how ageing is influenced by individuals’ earlier lives.