In this post Skeena Williamson and Lucinda Allen from the Health Foundation discuss levels of poverty and deprivation among social care workers.

Social care workers play a vital role in society but are among the worst paid in the UK. Little is known about their experiences of financial hardship. At the Health Foundation, we wanted to address this evidence gap. We looked at levels of poverty and deprivation among residential care workers and their families in the UK and how these compared to other workers.

Why did we look at poverty and deprivation among social care workers?

Over a million people work in the adult social care sector in the UK. They provide essential support with daily living to adults with a range of care needs, mostly because of disability and ill-health. Yet pay for care workers is low, last year the median wage was £9.50 per hour. Many also experience insecure working conditions, with almost a quarter of the workforce on zero-hours contracts. Staff turnover is high and vacancy rates are the worst on record in England.

Compared to other low-paid sectors, government has a bigger influence on pay in social care. Levels of central government funding, funneled through local authorities (or health and care trusts in Northern Ireland), help determine care providers’ budgets (of which staffing costs make up the majority). So, years of government underfunding of social care have limited how much providers can increase wages. But while devolved governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have recently introduced policies to improve pay in social care, action in England has been limited.

Low pay does not necessarily mean a worker will experience poverty and deprivation. But wages are generally people’s main source of income and low pay is associated with poverty and food insecurity in the UK. Previous analysis showed higher rates of poverty among residential care workers compared to all workers in 2013. We aimed to provide a more recent picture of poverty among social care staff in the UK, as well as looking at their experiences of deprivation and the factors that shape these.

What data did we use?

We analysed data from Households Below Average Income (HBAI) and the Family Resources Survey – national survey data used by government to monitor living standards in the UK. We focused on three measures of poverty and deprivation:

- the standard UK measure for poverty, defined as a household income below 60% of median household income (after housing costs).

- material deprivation among dependent children, looking at children in families who cannot afford certain goods and services and have a low household income (below 70% of the median)

- food insecurity, covering families experiencing low and very low food security who lack, or risk lacking, access to enough food.

Our analysis focused on workers in the residential care sector, a subset of the social care workforce who are mostly employed in nursing and care homes and assisted-living housing. We pooled data from 2017/18 to 2019/20 to increase the sample, except for the food insecurity measure which was only introduced in 2019/20. This gave us a sample size of 1,488.

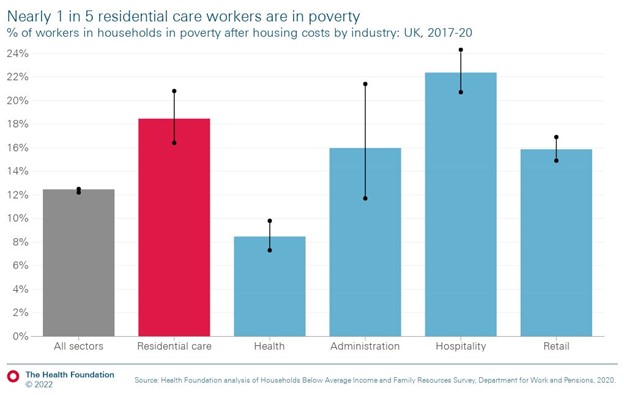

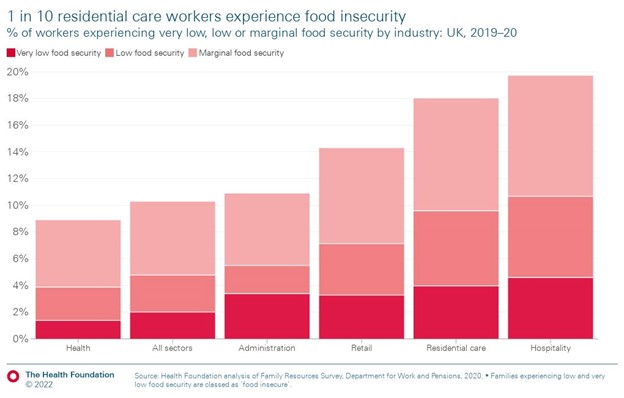

We compared rates of poverty and deprivation among residential care staff with levels among all UK workers and those in industries which compete with the social care sector for staff: health, administration, hospitality and retail. Recent Health Foundation analysis finds that the lowest paid care workers are most likely to come from sales and retail assistant roles. When leaving, they most commonly move into nursing roles. Administration, hospitality and retail are also among the lowest paid sectors.

There were several limitations to our analysis. These included having to restrict our analysis to the residential care sector and exclude staff in other care settings because of limitations with other relevant groupings for employment sectors in the data (for example, home care workers were grouped with staff in children’s nurseries). We also didn’t use data from 2020/21 because of the impact of the pandemic, which meant the sample size was much smaller than previous surveys. And pandemic measures (such as the furlough scheme) meant that data on income and living standards were difficult to interpret and not comparable to previous years.

What did we find?

Our findings paint a grim picture of living standards among residential care workers. From 2017/18 to 2019/20, nearly one in five experienced poverty (18.5%). This was similar to other low-paid sectors but higher than workers in all sectors (12.5%) and in health (8.5%).

We also found that residential care workers (19.6%) were around twice as likely to draw on Universal Credit and legacy benefits than all workers (9.85%). Underreporting by respondents means this is likely to understate workers’ reliance on state support to make up for low income.

During this same period, around one in eight children (11%) living in a family with a residential care worker was materially deprived. This could include not having access to a warm winter coat or access to fresh fruit and vegetables. The rate of material deprivation among children was 7% in all sectors and 2.8% in households with a health care worker.

Before the cost-of-living crisis, residential care workers were also more likely to experience food insecurity than all workers and health care workers. Nearly one in ten (9.6%) experienced low or very low food security.

Sadly, in many ways these findings are unsurprising when you consider the factors affecting the likelihood of experiencing financial hardship in the UK. Social care workers are mostly women and more likely to be from black and minority ethnic backgrounds. We also found that residential care workers are more likely than the average UK worker to have a longstanding illness, work part-time, be the only adult in their family and live in rented housing. All these factors increase their risk of living in poverty and deprivation.

What are the implications?

Our findings demonstrate the stark reality that, for many residential care workers, work is not a reliable way out of poverty and deprivation. Further analysis is needed to understand how financial hardship affects staff in the home care sector (who often face different challenges, such as not being paid for travel between people’s homes). It is likely that our analysis understates levels of poverty and deprivation among the care workforce. The current cost-of living crisis risks making their lives more difficult, as recent BBC reports of care providers resorting to giving out food packages to staff show.

Increasing pay and improving work in social care should be a priority for government in England. Additional funding for social care was announced in the Autumn Statement 2022 and a rise in the minimum wage in April 2023 will increase pay for many care workers. But there is uncertainty as to how far the extra money will go. Previously, underfunded increases to the minimum wage have increased pressure on staffing budgets and narrowed the difference in pay between the least and most experienced care workers.

Looking ahead, government must develop a long-term workforce plan for social care, including measures to increase pay and improve terms and conditions for staff. This will require further investment and measures to ensure money reaches workers. Potential options like a sector-specific minimum wage or sectoral wage board need to be looked at in the round as part of a comprehensive strategy for supporting and growing the care workforce.

Beyond social care, broader cross-governmental policy action to improve living standards is also necessary. Measures to reduce household poverty could include more affordable childcare and reforms to increase protections for private renters. Tackling poverty is necessary and urgent, not only for care workers but for all those who are struggling.

This blog is based on findings from a Health Foundation report on ‘The cost of caring: poverty and deprivation among residential care workers in the UK’. The Health Foundation is an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and health care for people in the UK.

About the Authors

Skeena Williamson

Skeena undertook a year-long internship in the policy team at The Health Foundation. In this role, she contributed to a variety of projects on health and care, with a particular interest in workforce issues. She has an MA in Social Policy from the University of York and a BA in Anthropology and Sociology from Durham University.

Lucinda Allen

Lucinda is a senior policy officer at the Health Foundation, focusing on adult social care in England. Her work has included assessing national government support for the social care workforce during the pandemic and looking at care and support services for younger adults. She has a particular interest in international recruitment into social care and has an MSc in Migration Studies from the University of Oxford.