Matthew Jay, Research Fellow and Data Scientist at the UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, introduces the ECHILD project that links data on children in state schools with data from NHS-funded hospital.

Matthew Jay, Research Fellow and Data Scientist at the UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, introduces the ECHILD project that links data on children in state schools with data from NHS-funded hospital.

We have recently seen significant investments in administrative data sharing and linkage across the public sector. Initiatives such as Health Data Research UK, the ESRC-funded Administrative Data Research UK partnership, and the Ministry of Justice’s Data First programme have all begun to realise the enormous potential that data linkage across different sectors can have. Given the nature of administrative data, these linkages enable new research that would previously have been impossible.

One such initiative that we have been leading is the Education and Child Health Insights from Linked Data (ECHILD) project, which, for the first time, brings together data on all children in English state schools with data from NHS-funded hospital contacts. Linkage between mothers and babies means we can also investigate intergenerational factors that affect maternal and child health. Here we briefly describe ECHILD and its contents, show an example from recent research, and describe how we are supporting the research community to exploit this exciting new resource.

What is ECHILD?

ECHILD consists of several, linked data resources covering all of England. The core datasets are the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and National Pupil Database (NPD). These cover, respectively, all English NHS-funded hospital contacts and all enrolments in English state schools. HES provides rich diagnostic and procedure in inpatients data that can be used to identify groups of children and young people with various conditions and presentations. Information from outpatients and Accident & Emergency visits is also available. Linkage to NPD provides data on school enrolment, absence, exclusion, special educational needs and exam results across primary and secondary school. As both datasets are longitudinal, it is possible to examine associations between health and education factors over time and in both directions. Data are available for people born from 1 September 1984 onwards (though each data module has different coverage; for example, NPD enrolments are only available from 2001).

In addition to the core datasets, ECHILD contains a number of other resources. These include mental health services data, maternity services, community services and children’s social care (children looked after and children in need). There is therefore scope to examine not just hospital contacts but other services around the child and family that may be relevant to health and education outcomes.

Example of use

ECHILD can be used to study a broad range of topics to do with children’s health and education, including methodological studies (e.g., studies about using administrative data). The five themes that ECHILD has been approved for are:

- Informing preventative strategies by healthcare and education services

- Informing children and their parents

- Informing education and clinical practice

- Identifying groups who could beneft from intervention

- Understanding the most effective methods for working with linked health and education data

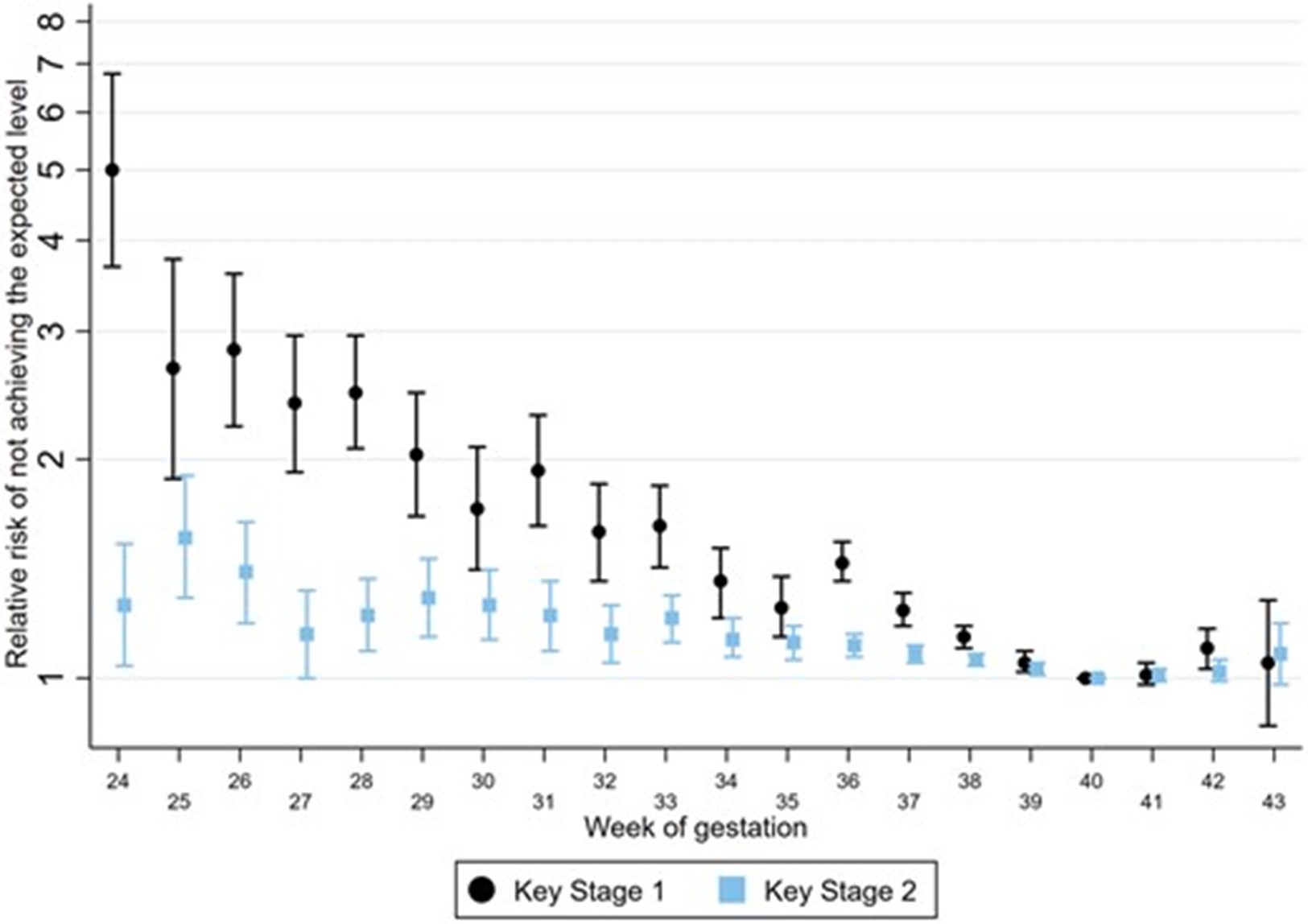

To take one published example, Libuy and colleagues used ECHILD to examine gestational age at birth and its association with primary school exam results. Their key findings are shown in Figure 1, which shows the relative risks of NOT achieving the expected standard at Key Stage 1 (age 6/7) and Key Stage 2 (age 10/11), comparing each gestational age in weeks with 40 weeks (term birth). The higher the dot, the worse the outcome. What is striking is a very clear gradient from 24 weeks to 39 weeks: those born more prematurely were less likely to achieve the expected standard. This study also showed that children born later than 40 weeks were also at slightly increased risk of not achieving the expected standard, meaning that attention should be paid to children born late-term, too.

Figure: Association between gestational age at birth and school attainment at Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2. Figure shows relative risk (log scale) comparing children born at each week of gestation with those at 40 weeks of gestation, adjusted for sex, parity, size of gestation, mode of delivery, maternal age, ethnic group, quintile of deprivation and expected month of delivery. KS2 results are adjusted for KS1 attainment: not achieving Level 2 at Key Stage 1. Results shown are for children born between 1 September 2004 and 31 August 2005 with a birth record captured in HES. Reproduced from Libuy et al. View an accessible table version of this data here.

“What is special about ECHILD here,” explains Prof Katie Harron, senior author of the paper, “is that it enabled us to look at gestational age in single weeks. If we had adopted a more traditional sampling-based approach, it is unlikely that we would have had a large enough sample to carry out these analyses in this level of detail. This is especially true when considering the need to look across primary school: ECHILD is not subject to attrition in the same way that traditional study designs are.”

How we are supporting the research community

Working with administrative data is complex. The primary strength of ECHILD is that we have a governance structure in place that very significantly simplifies data access for researchers and government users. Users are able to access a research-ready resource in a relatively quick period of time.

Nonetheless, many, especially new, researchers face other barriers to using administrative data owing to the complexity of raw file structures, opaqueness in documentation, sheer size of the data, and the fact that the data are not collected for research purposes. To help, the ECHILD team has been working hard to foster a community of users and provide resources to ease the learning curve and help researchers realise the potential of ECHILD faster.

Among other things, these include training courses with synthetic data (our first course was held in March 2024), community engagement events, our on-line documentation and data catalogue, an on-line discussion forum and shared resources via the ECHILD and UCL Child Health Informatics Group GitHub pages. We are also currently developing a phenotype code list repository, which will be a fully searchable database of code lists, along with comprehensive documentation and example code, that can be used to identify various conditions and other statuses in ECHILD.

Where to find more information

Our website should be your first port of call. There you will find more about ECHILD including links to our documentation and other resources and information on how to access ECHILD. You can get in touch with any queries at ich.echild@ucl.ac.uk. You can also find out more about ECHILD and its constituent data resources in a series of data resource profiles that members of the team have produced over the years:

About the author

Matt Jay is a Research Fellow and Data Scientist at the UCL GOS Institute of Child Health. His interests lie in using administrative data to understand the health and well-being of families, especially those using the family courts. He loves learning languages and writing music.