In this two-part blog post, Dan Muir, Senior Economist at Youth Futures Foundation and past Data Impact Fellow, discusses what impact evaluation is and why it matters.

My training in impact evaluation started during my master’s degree in economics. We had the choice of various specialisms to take, which entailed taking certain modules. There were the usual macro-economic, financial markets and other common options, but I had always had a keen interest in public policy, particularly relating to labour markets and education. This is where I felt my main interest, social mobility, most clearly sits. So, I choose this specialism towards the end of my studies, which has now evolved into a highly specialised and somewhat niche early career!

I still struggle to explain my job to new acquaintances, having not yet nailed down the elevator pitch. Impact evaluation is quite a small world, but the more I learn the more I appreciate how important it is, and believe it should play a much larger role in shaping public policy. In this blog, I’ll try to give a quick introduction to the impact evaluation world – what it actually is, why it exists, and some of the methods available to researchers.

What is impact evaluation?

If I was asked to summarise impact evaluation in three words, I would respond with “causation not correlation”. If it starts raining, this causes me to get wet. But an increase in ice cream sales does not cause an increase in the number of people that are sunburnt – these phenomena are correlated because they are both causally affected by the weather. The relationship between ice cream sales and the prevalence of sunburn is characterised by endogeneity – where the relationship between X and Y is driven by Z, known as a confounder. Endogeneity also characterises two-way relationships – where X affects Y, but Y also affects X.

Endogeneity exists in all walks of life, especially in the impact evaluation space. Consider one of the key issues our labour market, and for that matter our economy as a whole, currently faces – the economic inactivity crisis. Currently in the UK, the number of people not in work due to health conditions or sickness is far higher than it was pre-pandemic.

The previous Conservative government looked to address this through their Back to Work Plan, and tackling this crisis is also high on the new government’s agenda. The relationship between health and work, which sits behind this crisis and the various policy responses that have been and will be introduced, is characterised by endogeneity.

Working can lead to better health – receiving higher incomes can improve one’s diet or access to activities and exercise, the job itself may require physical activity, the social aspect of work can improve wellbeing, as can the sense of purpose work provides. But similarly, health is a key determinant of work outcomes – a healthier individual is able to work harder and for more hours. As such, if we were to simply compare the work outcomes, e.g., their salary, of a healthy and unhealthy person (oversimplifying things for the purpose if this exercise of course) and say that any difference in their salary was causally due to the difference in their health status, we would be wrong. This is where impact evaluation comes in. Stripping out all the noise and other contributing factors, impact evaluation seeks to understand what impact does policy X have on outcome Y?

Some key terms!

In order to come up with the answer to this question, impact evaluations have to wrestle with a key problem. First though, some key concepts and terminology.

In this space, the thing that we are trying to evaluate is known as the intervention. In the world I work in (policy focussed on youth employment), this could be for example the newly announced Youth Guarantee that forms part of Labour’s Back to Work plan (helpfully named the same as that of the previous Conservative government!).

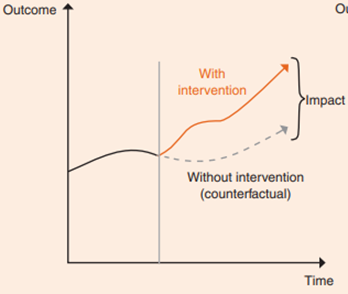

Another key term is the treatment group – these are the individuals that experience the intervention, so in this case all the 18-21 year-olds that will go through the Youth Guarantee. In order to understand what impact the Youth Guarantee has on their outcomes, such as whether or not they are in employment at the end of the programme, their future earnings, etc., those that are evaluating the policy will need to derive a counterfactual for the treatment group – this is what their outcomes would have been in a world where the Youth Guarantee had not taken place. By comparing the difference between these worlds, we would know what the causal impact of the Youth Guarantee had been – this is visualised in the graph below from the ILO’s guide on impact evaluation methods.

Image from ILO Guide on Measuring Decent Jobs for Youth

You may well have guessed then what the key problem with this is – of course, we only experience one of these worlds. The Youth Guarantee has/ will be introduced (putting aside any implementation issues), so we now live in the world with the Youth Guarantee. Unless a portal allowing us to access an alternative reality is invented soon, we will never get to see what the outcomes of the young people that go on to participate in the Youth Guarantee would have been had it not been introduced. And therefore, we can’t see what their counterfactual outcomes would have been, and therefore what the causal impact of the policy being introduced is.

This is then where the family of impact evaluation techniques come in – they seek to identify a suitable counterfactual in our Youth Guarantee world, in order to estimate what causal impact it has had. There are broadly two approaches to doing this:

- Introduce an experiment where you randomly assign individuals to either experience the intervention or not.

- Identify a comparable group that does not experience the intervention, for example because they are ineligible or choose not to.

In order for the counterfactual produced by these two approaches to be of a high quality, the group used to compare outcomes to the treatment group (known as the control or comparison group) needs to have certain characteristics. Firstly, they need to be similar to the treatment group in terms of characteristics that could affect their outcomes regardless of the intervention i.e., addressing the issue of endogeneity. They should also be expected to react to the intervention in a similar way, and should also have similar exposure to other interventions occurring at the same time that could also affect their outcomes – so for instance, the new national jobs and careers service that was also announced at the same time as the Youth Guarantee.

So, we now have an understanding of what we need to evaluate the impact of an intervention. In the next post I’ll talk about some of the techniques we can use to quantify impact in a case like this.

You can read part two of Dan’s post here.

About the author

Dan was part of the 2023 cohort of Data Impact Fellows and works as a Senior Economist at Youth Futures Foundation. In this role, he is working to develop a programme of Randomised Controlled Trials with employers to assess how recruitment and retention practices can be changed to support the outcomes of disadvantaged groups of young people. His main research interests include unemployment and welfare, low pay, and skill demand and utilisation.