The alleged misuse of Facebook data being used to win elections has featured in the press in recent weeks, including The Guardian, with the Information Commmissioner’s Office reported to be “conducting a wide assessment of the data-protection risks arising from the use of data analytics” (The Guardian, 2017). Libby Bishop, Producer Relations Manager and expert on the ethics of re-using data and informed consent at the UK Data Service, discusses the ethical considerations and the importance of setting standards when using social media data.

The alleged misuse of Facebook data being used to win elections has featured in the press in recent weeks, including The Guardian, with the Information Commmissioner’s Office reported to be “conducting a wide assessment of the data-protection risks arising from the use of data analytics” (The Guardian, 2017). Libby Bishop, Producer Relations Manager and expert on the ethics of re-using data and informed consent at the UK Data Service, discusses the ethical considerations and the importance of setting standards when using social media data.

Background

In 2007, David Stillwell, lecturer in Big Data Analytics and Quantitative Social Science and Deputy Director of The Psychometrics Centre at the University of Cambridge, and Michal Kosinski, Assistant Professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business, developed the myPersonality Project which analysed psycho-demographic profiles of over eight million Facebook users, using a Big Five personality questionnaire, one of the most popular scientific measures of personality.

According to the findings of the research, 10 Facebook likes enabled researchers to know more about a person than their average work colleague, and 300 likes gave them more insight into a person’s personality than their partner had (University of Cambridge, 2015).

Participants in the MyPersonality Project gave express consent for their data to be shared as part of this research. However, recent articles in The Guardian suggest that the personality prediction method published by Stillwell and Kosinski may have been used in political campaigns.

Ethical considerations in using social media data

The suggestion that the personality prediction method may have been used for political campaigns raises a number of ethical questions. How is consent to use these data established? – and in the case of there being no express consent given for a particular defined purpose, is it right to infer consent for the re-use of personal data that has been provided on a public platform? Are social media data public? And if they are, does that imply that they can be freely disseminated? Where should the line be drawn in terms of what is considered to be a public and/or private platform?

Even if the legal case was clear (and it is not), not everything legal is ethical. Researchers are bound by ethical principles above and beyond legal compliance. Foremost among these is the duty to minimise harm to research participants. Such principles are at work when leading social media researchers, such as those at the Social Data Science Lab at Cardiff, set a higher standard and seek informed consent from Tweeters when they quote identifiable individuals in their research outputs.

It may seem relatively straightforward to argue that Twitter is a public platform, and that anyone who freely provides personal data on this platform is thereby consenting for these data to be shared, but defining whether a platform is public or private is not always so simple. Facebook for example, is used as a tool to share personal information with an individual’s ‘Facebook friends’. Are users aware that people outside their network of friends could be able to view their information? And if so, do they have the ability to change the default settings?

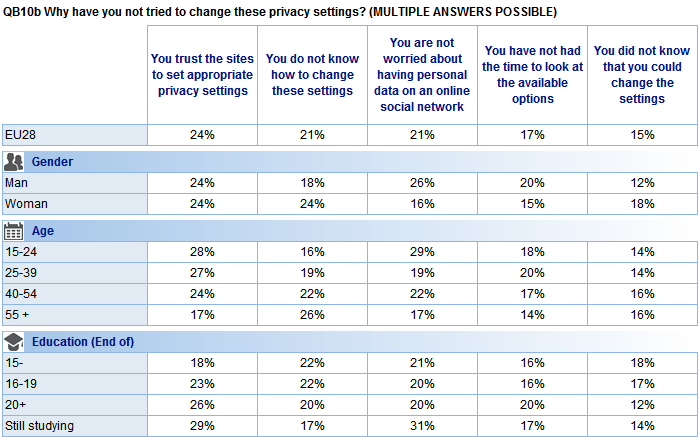

The Special Eurobarometer 431 survey on Data Protection commissioned by the European Commission in 2015, showed that 15% of people who had not altered their privacy settings on social media were unaware that they could change their default settings. The survey also showed that that 42% of respondents had never attempted to alter the privacy settings of their social networks’ profiles from the default settings.

Given the variety of reasons cited for not trying to change the privacy settings in the Eurobarometer 431 survey, outlined in the table below, it would be wrong to assume that failure to change privacy settings infers consent to share data.

Eurobarometer 431 survey respondents who have not tried to change their default privacy settings

However, social media providers appear to be evolving their practices to address privacy concerns. As of 22 May 2014, Facebook switched its default setting to private (up until then anyone on the internet could view someone’s content), with the company acknowledging that “it is much worse for someone to accidentally share with everyone when they actually meant to share just with friends, compared with the reverse” (Facebook, 2014). They also announced the roll-out of an ‘expanded privacy check-up tool’ to remind people to review who their posts are seen by and the privacy settings of information shared on their profile.

The challenges of using social media data

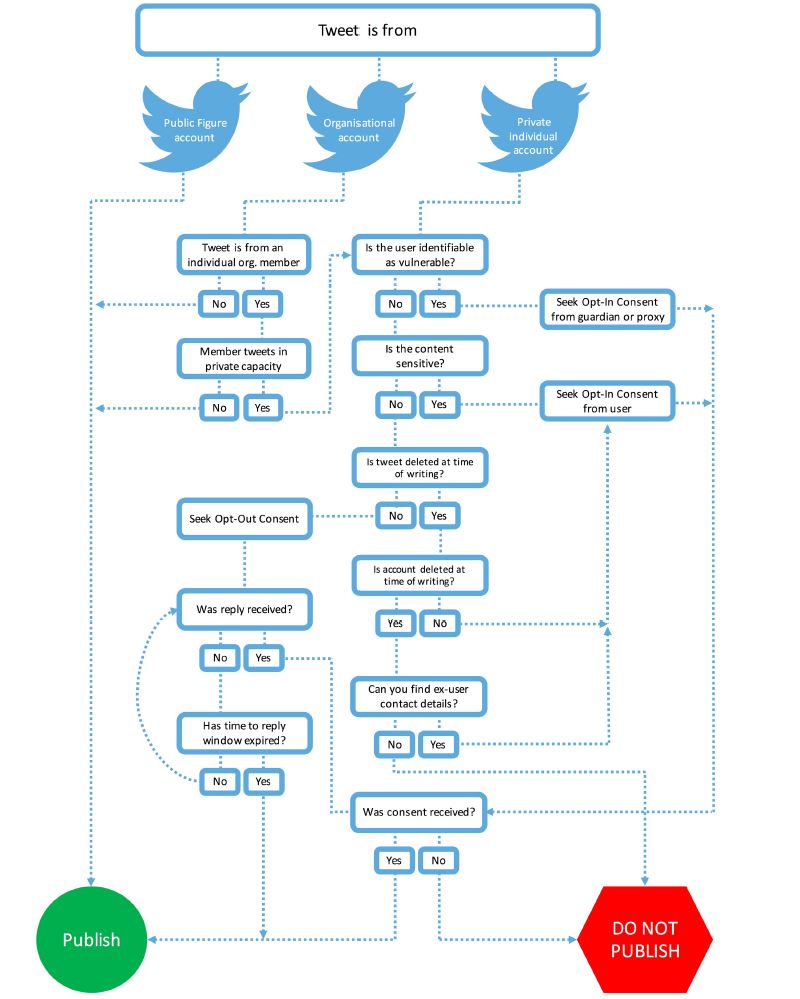

The analysis of social media data presents a number of challenges, including ethical and legal ones associated with consent and anonymisation. For example, our Big data and data sharing: Ethical issues guide, mentions an example of a researcher, Dan Gray, who collected some 60,000 Tweets in 2015 for his research, but was unable to anonymise the Tweets because Twitter’s Terms and Conditions prohibit modifying content. Although Twitter may be viewed as a public platform, survey analysis by the Social Data Science Lab, where Gray was connected, showed that Tweeters did not want their content used, even for research, if they were identifiable.

Professor Matthew Williams from the Social Data Science Lab therefore developed a Tweet Publication Decision Flowchart (flowchart can be found on page 18), a handy tool for researchers wishing to use Twitter data.

Tweet Publication Decision Flowchart

The UK Data Service Big Data Network Support team is here to help researchers to make the most of big data, including social media data, for knowledge exchange and impact. Find out more on our website.

Related Data Impact Blog post: Using big data responsibly: the ethics of big data by Libby Bishop and Felix Ritchie.

Good analysis, in terms of Facebook measure have certainly been taken to tighten up privacy settings since.