Karen Mansfield explores the opportunities and challenges of data governance from multiple perspectives.

Karen Mansfield explores the opportunities and challenges of data governance from multiple perspectives.

My work on MRC Pathfinder projects in Oxford, and later the development of a Data Protection Impact Assessment for the OxWell Student Survey, forced me to consider both the opportunities to a data-driven approach and the challenges to data sharing from multiple perspectives:

- as an analyst applying to access and link administrative data for research

- as a researcher wishing to collect and share anonymous extracts of research data for open science purposes

- as a data custodian wishing to ensure the confidentiality of the data participants

- as a parent of three data subjects in some of those datasets.

Between the daily problem-solving and discussions with information compliance, information security, ethical, legal and contracts teams, I often asked myself: is this science or ‘admin’?

Endless Possibilities

I had some previous experience of working with rich data from a large-scale, multi-national, cognitive training intervention, where I had collected, cleaned, integrated and analysed electrophysiological, behavioural, self-report and demographic data from thirteen training sessions plus pre- and post-tests.

Besides the original planned research questions around the effectiveness of the intervention, I realised that so much more could be learned using data-driven approaches. Follow-up questions could address the mechanisms behind the limitations to the intervention and inform the design of more successful future interventions, if not by the team that designed the intervention and collected the data, then by others with relevant expertise.

The scale of the data from the hundreds of participants that took part in that cognitive training study pales in comparison to the scale of the administrative datasets that the MRC Pathfinder projects aimed to integrate and analyse.

The public interest research possibilities offered by de-identified linked administrative records, such as collected in health, education or social care settings, are infinite – such research can investigate dynamic influences on real-world outcomes in the relevant clinical or population samples.

Endless application procedures?

But during my first Pathfinder task, I soon discovered that applying to link administrative health, education and social care data faced even greater challenges, such as whether the pseudonyms in the linked data can be traced back to real IDs and which party will link the pseudonyms from the different datasets.

I spent considerable time thinking how to work through these problems, including discussions with the data-sharing team for the National Pupil Database and information governance experts. Eventually we decided to delay our application and think more carefully about potential linkage models before developing one to put into a business case.

The start of the MRC Mental Health Data Pathfinder awards coincided with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

In hindsight, this probably wasn’t pure coincidence. Concerns about confidentiality for data subjects are completely understandable but can seem in conflict with Open Research.

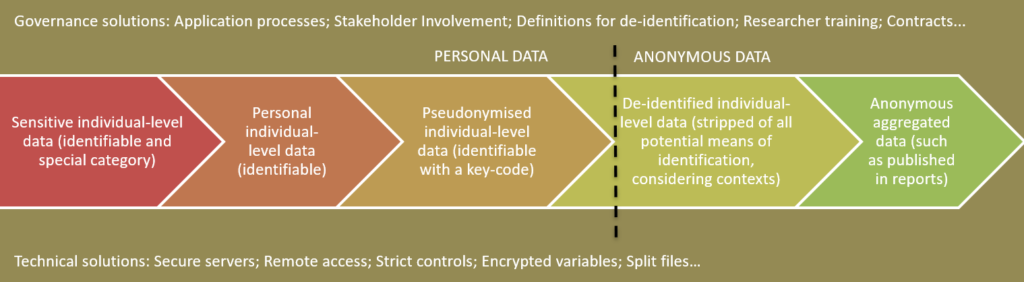

With the GDPR, the distinction between anonymous and pseudonymous became more explicit, and the idea that the large-scale de-identified individual-level datasets that are so valuable for data-driven research could be considered anonymous came under question.

Seemingly increasing delays in access to administrative data for public interest research led a consortium of researchers, me included, to write a commentary published in the Lancet Digital Health.

We described examples of delays to accessing data and the resulting impact on mental health research, attempted an analysis of the underlying problem, and set out a suggested plan of action to improve the situation.

My main contribution was to describe why I think that fear of data breaches was the primary cause of the increasing delays, together with some thoughts on how to mitigate the risks and the concerns.

Luckily, schemes like the Office for National Statistics Approved Researcher Scheme and the UK Data Service Safe Researcher Training are already making it safer to share and access personal data for research, and easier to work through the admin. Thorough training in data protection and appropriate agreements before accessing the data can help ensure confidentiality.

However, we the researchers and analysts also have much to learn if we want to be able to access and contribute to Open Data resources, whereby the data extracts need to be both valuable to research and anonymous.

So what is anonymous?

Studies using large-scale data such as linked administrative records should be possible using anonymous data, as the analysts don’t need to know who the participants are.

However, the richer the data are in demographic or contextual information (for example, socio-economic or location information), the higher the risk is that the data subjects could be identified by somebody trying to do so.

Even surveys like the OxWell Student Survey, which don’t collect person identifiers or use unique logins, and even minimise the collection of demographics, must consider potential contexts in which the chance of identifying participants in the data increases, such as by someone who knows the participants. As such, these sorts of datasets need to be classified as personal data (falling under GDPR), and sharing must adhere to the relevant privacy information shared with the data subjects as well as high data security standards.

Although researchers don’t want to identify the data participants and just want to extract informative summaries of results from the data, informative analyses often require the inclusion of multiple key demographic and contextual variables to accurately account for the different sources of variance in the data.

For example, the health and development of children and adolescents will depend on the availability of good nutrition (i.e. family income) as well as air pollution (home location).

Sometimes it feels like data protection officers are just there to reduce the validity of our analyses by asking us to limit our selection of variables, but where it is possible to ensure the data collected or requested are anonymous, then we can save ourselves a lot of time (and paperwork) at the same time as protecting the identity of the data subjects.

Knowing what makes a specific data extract anonymous, pseudonymous or identifiable is not always straightforward, but the Information Commissioner’s Office recently published guidelines on anonymisation and are requesting our feedback.

Figure: Definitions of personal and de-identified data that can apply to the administrative data that researchers request to address key mental health research questions. The line dividing personal and anonymous data depends on the probability of being able to identify individuals in the data with any reasonable means. This probability reflects many aspects, such as the number of data fields, whether demographic measures are included, and considering all contexts in which the data could be seen (for example, by analysts with access to other datasets).

Larger version of figure / accessible pdf of figure.

Conclusion: More science than admin

What I have learned is that, in applications for extracts of large-scale data, the research team should be as selective as possible in the variables requested, increasing the chances that the data needed are anonymous. Otherwise, the application and approval process becomes longer, and in some cases sharing for research is not permitted due to a conflict with the privacy information shared with the data subjects.

Data linkage remains a challenge because some form of meaningful identifiers or pseudonyms are required for matching.

Machine learning approaches face similar challenges in that a broad range of potentially informative variables are needed for the analysis, and some algorithms might increase the risk of re-identification.

In some cases the analysis just won’t be worthwhile with an anonymous extract, but careful consideration of the variables needed for the project will facilitate both linkage and data applications.

Similar considerations need to be made by research teams planning to collect data intended to be shared for open research.

Most important is to predict potential data governance challenges and delays at the point of the research design and applying for funding, before applying for ethical review.

During the project, the whole team, from Principal Investigators, postdocs, research assistants and support staff need to be involved in data protection discussions and offer suggestions for data minimisation that won’t eliminate the validity of the analyses.

Ideally, studies should consider from the outset what will be possible to successfully anonymise the data without eliminating key associations, increasing the potential value and future uses of the data.

Where I once thought that working through these issues was just part of the ‘admin’, I now think that considering data protection from multiple perspectives is a key part of the study design, particularly in the era of Open Research. It might take a while but eventually data protection will be accepted as part of the science rather than the admin.

About the Author

Dr Karen Mansfield is a Postdoctoral Research Scientist for the OxWell Student Survey and the Research coordinator for Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre – Informatics and Digital Health. Karen is interested in solving methodological challenges in the collection, integration, analysis and safe-sharing of data to inform mental health and wellbeing research.