Ben Brindle, Researcher at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory, explains how the new Hong Kong BN(O) Migrants Panel Survey will shed light on migrants’ integration into UK economy and society.

Ben Brindle, Researcher at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory, explains how the new Hong Kong BN(O) Migrants Panel Survey will shed light on migrants’ integration into UK economy and society.

Who are the BNOs?

In January 2021, Boris Johnson’s Conservative government launched a new visa route that allowed Hong Kongers with British National Overseas (BNO) status and their family members to move to the UK.

The decision, which followed China’s passing of the controversial National Security law, gave rise to one of the largest migrant inflows to the UK from a single source country ever recorded. Almost 180,000 people were granted a BNO visa between January 2021 and March 2025. (For context, 273,000 visas have been granted to Ukrainians since Russia’s invasion). Compared to other visa routes, the BNO scheme comes with relatively few restrictions.

Visa holders can work or study in the UK, and while they aren’t eligible to claim benefits, they can use the NHS. At the time of writing, BNOs can also apply for settlement after five years (and then British citizenship after a further year), although this qualifying residence period may increase under Labour Party proposals announced in May 2025.

Given the potential for BNOs to stay in the UK permanently, it’s important for policymakers to understand how well they integrate into the UK economy and society—not just in the months after they arrive, but also in the years following. This is where our BNO survey comes in.

What is the Hong Kong BNO Migrants Panel Survey?

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to track a major migrant group from (almost) the time of their arrival in the UK.

In the first wave of interviews, which took place last summer, we interviewed approximately 2,100 BNO visa holders from 1,000 households.

The invitation to complete the survey was sent by the Home Office to a random sample of email addresses tied to BNO visa applications. Recipients did not have to accept the invitation, and the Home Office played no further part in the data collection.

The survey questions were wide-ranging. We asked respondents about their home and family, economic and financial situation, perceptions of discrimination, and health and well-being. The survey also included BNO-specific topics, such as their reasons for moving to the UK, remittance patterns, and future migration intentions.

However, migration is not a one-off event – the situation and needs of the BNOs will change over time. They might change jobs or move from one part of the UK to another, and their ties with the local community or future intentions may evolve.

So, to understand BNO visa holders’ trajectories following migration, we’re interviewing our respondents this year and then again in 2026. The survey questions will evolve, too. While some will feature in all three waves, we’ll ask others less frequently. For example, in the second wave, we’ve included a political module, which asks BNOs how they voted in the 2024 general election and their broader political views.

To support comparisons of BNO visa holders with other migrants and minority ethnic groups in the UK, we have drawn on questions asked in the large and long-running longitudinal Understanding Society survey.

When future waves of the survey have been completed, the full dataset will be deposited into the UK Data Service data collection.

Why did BNOs come to the UK…

Perhaps the main reason it’s so unclear how BNOs will integrate into the UK economy and society is because the BNO visa route isn’t like any other route people can use to come to the UK. While it was introduced as a humanitarian route, the characteristics of BNO visa holders more closely resemble those of migrants on work visas. However, it may be the case that respondents’ outcomes are related to the reason they came to the UK…

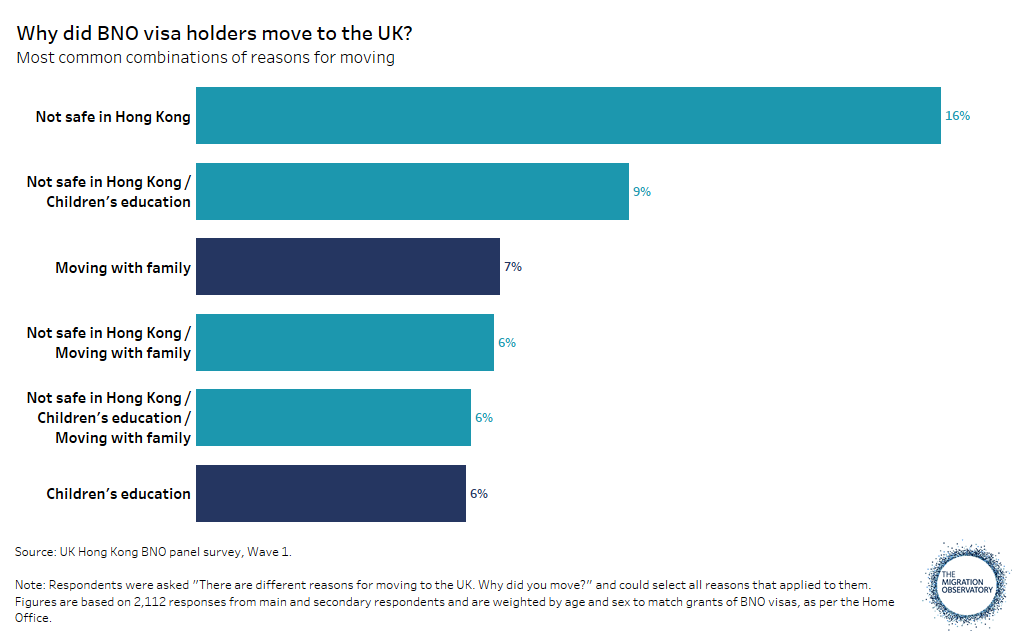

When we asked BNOs why they came to the UK, the most common reason by far was ‘Did not feel safe in Hong Kong’. Two-thirds of respondents gave this reason, followed by a ‘To give my child(ren) a better education’ and ‘Moved together with family members’ (both 35%). But this is an oversimplification, because many of our respondents moved for several reasons.

In total, our respondents gave 139 different combinations of reasons for coming to the UK. Hong Kong being unsafe was still the most common reason, but some gave other reasons alongside this, and some didn’t mention safety in Hong Kong at all.

Table 1 – Why did BNO visa holders move to the UK?

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

To see if BNOs’ economic and social integration in the UK is related to their reason for migration, we can split our respondents into four reason-for-migration groups.

First, there are those who gave ‘work’ as one of the reasons they came to the UK (11%); second, people who only said Hong Kong wasn’t safe (16%); third, people who said Hong Kong wasn’t safe and also gave at least one other reason (43%); and fourth, people who didn’t mention either work or safety in Hong Kong (30%).

… and how was this related to their outcomes?

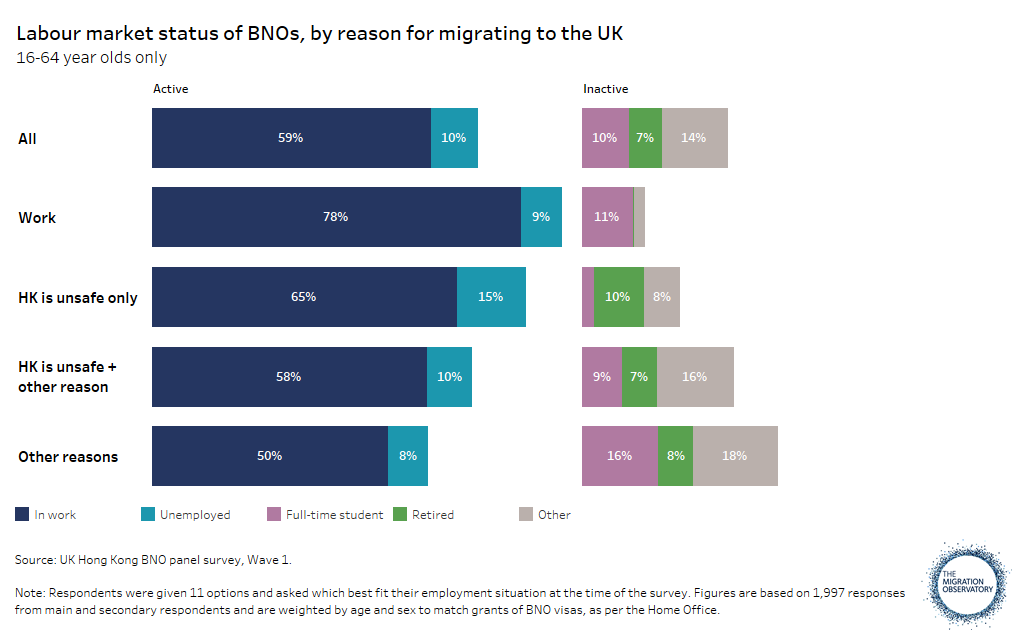

Overall, 59% of respondents were in work—a relatively low employment rate, similar to that of refugees living in the UK (58% in 2022). While the share of BNOs in employment will likely increase over time as they become more settled in the UK, there does appear to be a link to their reason for migration.

At one end, almost 80% of respondents who said work was a reason they came to the UK were in employment. At the other, only half of those who migrated to the UK for other reasons (i.e., not for work or due to safety in Hong Kong) were in employment. This is to be expected given many of this group came to do things which involve being out of work, such as full-time education or looking after the family or the home.

Table 2 – Labour market status of BNOs, by reason for migrating to the UK

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

Differences in employment rates may be related to each group’s English language proficiency. Migrants with better English language skills are more likely to be in work, and among our respondents, only 4% of the ‘work’ group said they had difficulty speaking day-to-day English, a very low share. This compares to 16% of those who migrated only because Hong Kong wasn’t safe and 17% of those who came for other reasons, shares closer to recent migrants more generally.

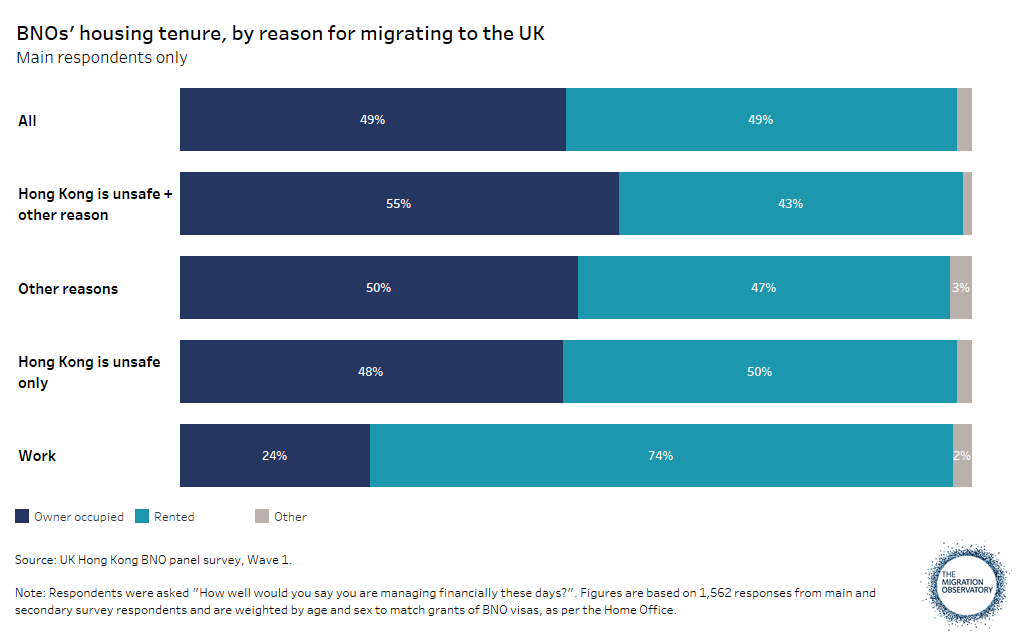

We can also see sizeable differences in homeownership by reason for migration to the UK.

Whereas 24% of the ‘work’ group owned their own home, this was the case for around half of BNOs who migrated either because Hong Kong wasn’t safe or for other reasons owned their own home. To put that into context, it’s a higher homeownership rate than for migrants living in the UK overall (43%), and particularly high compared to migrants who have lived in the UK for under 5 years (27%).

Two factors may explain this pattern. Firstly, the work group are younger on average: their median age is 33, compared to 43 for our sample overall. Secondly, this group was less likely to say they expected to stay living in the UK in the years ahead.

Table 3 – BNOs’ housing tenure, by reason for migrating to the UK

Larger version of image / Accessible version of data

What’s next?

The findings above offer a glimpse into the diverse motivations behind BNOs’ decisions to move to the UK, and how these motivations relate to their lives here. However, this is just the beginning. It remains to be seen how BNOs’ experiences and plans for the future evolve over time.

Future waves of the survey will allow us to build a fuller understanding as to how Hong Kongers have settled into life in the UK. The first wave of the survey should be added to SecureLab by the end of year, so stay updated to find out when.

About the author

Dr Ben Brindle is a Researcher at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory, which informs public and policy debates by providing impartial, evidence-based analysis of data on migration and migrants in the UK. He authors and co-authors briefings covering a range of topics – including UK migration statistics, migrant workers, and the impact of changes to UK visa rules – and is part of the Office for National Statistics’ Transformed Labour Force Survey expert advisory group. Ben is also a former UK Data Service Data Impact Fellow.

Comment or question about this blog post?

Please email us!