Daisy Fancourt explores whether arts and cultural activities can protect against cognitive decline and dementia.

Theories of cognitive reserve, disuse syndrome and stress have suggested that activities that are mentally engaging, enjoyable and socially interactive could be protective against cognitive decline and the development of dementia. Arts and cultural activities combine cognitive complexity with mental creativity and have been well-researched as interventions for people with dementia, with data suggesting improvements in a range of factors including mental health, loneliness, agitation, speech and memory recall.

However, whether the arts can also contribute to cognitive reserve and thereby act protectively to help prevent cognitive decline and dementia onset remains unknown.

Researchers at University College London have therefore been working on the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing to explore whether engagement with the arts is associated with better cognitive ageing.

What did we find out?

Study 1

Over the past year, we have conducted a series of studies on arts engagement in older age.

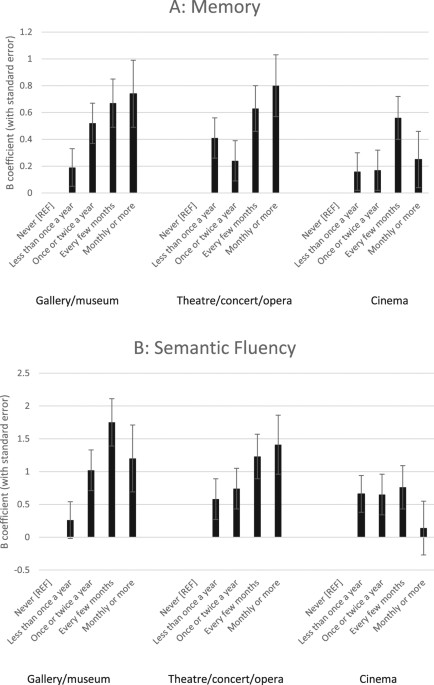

Two of these studies have focused specifically on cognition. In the first, we drew on data from 3,445 adults aged 52+ assessed over a period of 10 years (2004-2014). We used measures from neuropsychiatric test batteries, including immediate and delayed recall tasks as a measure of memory and object naming tasks as a measure of semantic fluency. Both of these measures have been shown to predict clinically significant cognitive decline.

We focused on the potential benefits of three types of cultural engagement:

- visiting galleries, museums or exhibitions;

- going to the theatre, concert or opera;

- going to the cinema.

We found dose-response associations between visiting galleries, museums or exhibitions and going to the theatre, concert or opera and smaller declines in memory and semantic fluency 10 years later. However, we found no clear associations between going to the cinema and cognition.

These analyses were all adjusted for baseline cognition as well as a range of other factors including demographic variables (sex, age, marital status, ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, occupational classification and wealth), health-related variables (including self-reported health, eyesight, hearing and depression) and engagement with other social or cognitively-stimulating activities (including social networks, civic and community engagement, whether participants had a hobby, whether participants used the internet and whether participants read a daily newspaper).

We found no evidence that the age of participants affected the relationship shown here. We also found no evidence that other factors such as mobility problems affected responses.

We ran a series of additional analyses as well to try and ascertain whether early symptoms of cognitive decline might have affected cultural behaviours and therefore cognition results, but found no evidence of this. These results therefore suggest that engagement in cultural activities could help to reduce cognitive decline in older age.

Associations between cultural engagement and (A) memory (B) semantic fluency.

Reproduced from Nature journal under a Creative Commons licence.

Study 2

In order to progress this work, we undertook some further analyses looking specifically at dementia incidence.

We again drew on data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, this time focusing on 3,911 adults who were free from dementia at baseline. We assessed whether they then developed dementia at any point over the following 10 years using a combination of physician diagnosis and responses to a validated informant questionnaire on cognitive decline. As visiting galleries, museums or exhibitions had produced the strongest result in the first study, we focused specifically on this activity in this second study.

Again, we found a dose-response relationship between cultural engagement and the risk of developing dementia, with a 49% lower risk amongst those who attended every few months or more compared with those who never attended.

Associations between visiting art galleries and museums and dementia incidence

Results in bold are significant.

Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for gender, age, marital status, educational attainment, employment, wealth and occupational classification. Model 3: additionally adjusted for eyesight, hearing, depression and existing cardiovascular health conditions. Model 4: additionally adjusted for community engagement.

Reproduced from The British Journal of Psychiatry under a Creative Commons licence.

As in the first study, we controlled for a range of factors that could have confounded this relationship, including demographic factors (gender, age, marital status, educational attainment, employment, wealth and occupational classification), health-related factors (including eyesight, hearing, depression and existing cardiovascular health conditions), and other types of community engagement.

We again found no meaningful differences dependent on age. We ran a series of additional analyses to ascertain whether preclinical symptoms of dementia might have affected our results but found no evidence of this.

What next?

These results suggest that cultural engagement could be protective against cognitive decline and the onset of dementia.

It is likely that this is achieved through contributing to cognitive reserve. For example, cultural engagement provides combined neural and sensory stimulation and cognitive engagement; it requires light physical activity to attend which could reduce the negative effects of sedentary behaviours; and it can reduce perceived isolation by encouraging people to leave their homes, meet with friends and interact with staff/other visitors.

However, these studies are observational rather than experimental. So to confirm causality, intervention studies that signpost older adults at risk of cognitive decline or dementia to cultural activities could be beneficial.

Programmes such as Social Prescribing and Museums on Prescription are currently providing this service in the UK and studies are being undertaken.

Given that cultural venues number highly (40,000 museums in Europe, the US and Canada alone) and reach diverse geographical populations and demographic groups, these institutions offer enormous potential as sites for public health interventions.

Data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing is available from the UK Data Service.

Dr Daisy Fancourt is a Wellcome Research Fellow in the Department of Behavioural Science and Health at UCL specialising in psychoneuroimmunology and social epidemiology. Her research focuses on the relationships between cultural and community participation and health outcomes across the lifespan.

Dr Daisy Fancourt is a Wellcome Research Fellow in the Department of Behavioural Science and Health at UCL specialising in psychoneuroimmunology and social epidemiology. Her research focuses on the relationships between cultural and community participation and health outcomes across the lifespan.