Evidence-based social policy depends on access to rich supplies of high-quality data. But how can we create, curate, enrich and reuse data already collected by government departments and researchers? James Nazroo and Matthew Woollard of the UK Data Service explore the network of trust and expertise that ensures a cost-effective pipeline of productive, policy-relevant data.

James Nazroo, a Deputy Director of the UK Data Service writes from a researcher’s point of view:

The launch of the UK Data Service signals a step-change in the way we use and reuse the products of our research. It is about making high-quality data (of all types) easy to get hold of, as easy as possible to use, and providing support for the use of such data. And, by providing an exemplar, it is also about encouraging and supporting others to set up ‘data stores’ that provide easy access to data either directly or through the UK Data Service. Doing this is not straightforward, taking the efforts of a large number of people and involving significant funds. So it is worth thinking about why it is important.

I’m an active researcher, involved in running data collections (most notably the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, or ELSA) and in using data produced by others (for example, this will be a major element of the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity, or CoDE). The UK Data Service is crucial to such research activities, as was its predecessor. The millions of pounds invested in data collections like ELSA are best used to generate data that a wide range of academic, policy and lay analysts can get their hands on. The ELSA data are being used to provide evidence on a wide range of issues — locally, nationally, internationally, short- and long-term — because they are accessible (as well as high quality). A recent IFS working paper exploring how the 2008-09 financial downturn affected older households in England is just one rich example.

Of course academics typically design data collections to address our particular research concerns. If we plan for wider use we must understand and design for others, and to do this we need to involve a broad constituency. For ELSA this has meant consulting with a wide range of disciplines and with policy analysts in a number of sectors, but also consulting internationally so a cross-national research agenda could be supported. A by-product of designing for a wide constituency and making data easily accessible is that our data outputs may be used by academic rivals, but to do otherwise would be wasteful. The longstanding social sciences culture of sharing data – making data accessible and usable – is one to value and one that is at the heart of the UK Data Service.

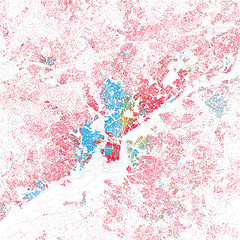

This is clearly demonstrated in the work we plan for CoDE. A central theme in our work is the proposition that the changing ways in which ethnicity is categorised reflect changing meanings of ethnicity – which identities become relevant in particular periods and contexts, why they are relevant, and how they are lived and racialised – and changing patterns of inequality. Following from this, to understand ethnicity now we need to also understand how it has ‘evolved’. So in CoDE we are planning to use data generated from the 1950s to the present day – local surveys, national studies, census data, etc. Almost none of these data have been generated by the CoDE team. So our exciting (at least from my perspective) agenda would not be possible without the past and current efforts of researchers to make their data available, and the current efforts of the UK Data Service to make data accessible and to support their use.

Support is important, because secondary use of data is not without problems. Some of these problems are obvious. For example, survey questionnaires may not adequately cover the concepts needed for the research, or sample designs might not be quite right, both of which might result in research agendas being modified. But there are also problems in getting to grips with and understanding the details of the methods used to generate the data and the implications of these for planned analysis. This is another area where the UK Data Service excels, not only making data accessible, but also providing support for their use.

Matthew Woollard, Director of the UK Data Service, adds:

James makes a convincing case for sharing research data and the support necessary to ensure that data can be used by researchers not involved with its collection. But what most researchers aren’t aware of is the infrastructure necessary to make digital data available and reusable over time. This is where archivists and digital preservation specialists play an important role.

A key part of the UK Data Service is to ensure the data received from researchers, survey subjects and government departments are formatted, contextualised and enriched in a way which ensures they are as usable as possible to researchers, while any curatorial decisions retain the purity of the original deposited data. These curation activities must also remain transparent to the data producers and users to ensure the archival phase of the data lifecycle is valued and trusted. Essentially, there must be a trust relationship between all players in these activities: researchers must trust that archivists are giving them the ‘right’ data, and data owners and producers must trust that the archivists are not damaging the integrity of their data.

Broadly, this is what the UK Data Service does every day. While many of our behind-the-scenes processes may be invisible to researchers, they are foundations necessary to support the needs of data producers, data users, funders and policy makers. In contrast with some of the giant datasets (such as earth observation satellites), social science data require more than simply looking after the bits and ensuring that file formats remain readable over time. An organisation hoping to support continued access to resources while keeping them understandable must be prepared to provide sufficient context not only in terms of documentation but also by defining how the data are related to each other.

The UK Data Service is based around a functional model, which in turn is based on the Open Archival Information System (an ISO standard). This means that we can work with proper standards for archiving digital materials building trust relationships. Over and above the need for a trusted archival storage system is to guarantee data integrity. The archival terms ‘fixity’ (assurance that any content alterations are accurately documented), ‘context’ and ‘provenance’ are critical for data to be used appropriately, whether for secondary analysis or the validation and replication of results. In addition, archives play a key role in tagging digital objects with unique and persistent identifiers (such as DOIs), which supports unambiguous reference and citation, simplifies the assignment of credit where it’s due (at both the data level and the publication level), and allows us to further enrich the environment of the data through appropriate linkage.

It is through the development of these supporting structures around the data — and crucially, making the data available as widely as safely possible through the application of clear rights and access — that trust and transparency are achieved. Many of these critical concepts are created and managed based on recognised metadata standards; at the UK Data Service, that includes the Data Documentation Initiative (DDI). It is generally acknowledged that the best time to generate rich, accurate metadata is as close as possible to data creation. Through the development of data lifecycle models, we can provide guidance and develop tools to create metadata which are packaged and maintained with the data throughout its journey.

In summary, our work to ensure easily referenced, authentic, linked data with clear provenance underpins the layers of supporting services, the assignment of credit and the assurance of accountability. These concepts are not only necessary to support further work, evaluation or decisions based on these valuable data assets; they are the building blocks for demonstrating true impact.

This post first appeared on the LSE Impact Blog and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License

James Nazroo is a Professor of Sociology and Director of the Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research (CCSR) at the University of Manchester.

Matthew Woollard is Director of both the UK Data Service and the UK Data Archive, based at the University of Essex.

I enjoyed this post.

I understand ESRC-funded researchers are asked to contact your service and offer their data. What crtieria do you use to assess the offer? What happens to the data your service decides it does not want?

Thanks

Hi Glenn

Please send over your email address and I’ll get some information over to you.