For her PhD research and a case study for the UK Data Service, Laura J Brown has used two British cohort studies to explore how environmental circumstances impact on whether women choose to breastfeed their babies.

For her PhD research and a case study for the UK Data Service, Laura J Brown has used two British cohort studies to explore how environmental circumstances impact on whether women choose to breastfeed their babies.

“Ok, so there’s my husband, he helps, my mum… but definitely not my mother in law…”

“What about beyond your immediate support network?”

“Hmmm, my health visitor, La Leche League of course, and then… I’m not sure”.

This is a typical response I heard new mums give when asked to draw their circles of support at the local breastfeeding support groups and antenatal courses. Mothers know all too well that support for breastfeeding is not unanimous and that they have to be selective in where they turn for help.

The LLL mothers are a select group. They are women who might need some extra nurturance and reassurance, but they are breastfeeding already or, in the case of expectant mums, have high intentions to do so.

But what about the mums who aren’t there? What about the mums who aren’t breastfeeding?

As I made cups of tea for these La Leche League mums, I pondered the wider circles of influence, and with my evolutionary hat on I thought about the importance of socioecological context. How might environmental circumstances impact women’s infant feeding choices and play into the clear socioeconomic gradient in breastfeeding seen in the UK?

By looking for environmental links in two UK cohort datasets – the Millennium Cohort Study and the Born in Bradford study – my PhD research hopes to add to our understanding of the variation in breastfeeding seen in the UK.

Assessing the environment

Using mothers’ responses to questions about their neighbourhoods as well as independent observer ratings of the streets where the millennium mums live, I created two summary scores of local environmental quality to see if these were associated with breastfeeding .

The evolutionary theory of life history suggests that animal physiology and behaviour patterns across a fast-slow continuum, with fast life histories favoured in harsher environments, typified by, for example, short lifespans, early maturation and reproduction and having several offspring. I wanted to see whether breastfeeding, a key marker of parental investment, was also responsive to environmental circumstances.

I predicted that better local environmental quality would translate into higher initiation and duration of breastfeeding and suspected that the more subjective measure based on mother’s own environmental perception would be a stronger predictor. I found that it was actually the independent neighbourhood assessments that more robustly predicted breastfeeding behaviour – for each unit increase in objective environmental quality, mothers were around 1.5 times more likely to initiate breastfeeding and around 10% less likely to stop breastfeeding in any given month.

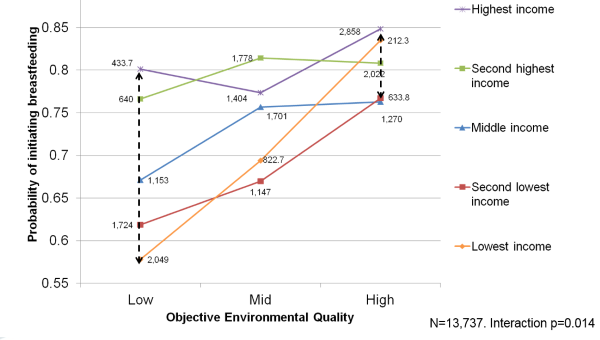

Family socioeconomic status acted as a buffer, protecting the breastfeeding chances of those with more resources, even in low quality environments.

The graph below illustrates this protective effect. The relatively smaller gap between income lines on the right compared to the left shows that mothers from higher-income households had relatively high breastfeeding initiation rates regardless of objective environmental quality (i.e. the neighbourhood assessment score); while breastfeeding initiation was more strongly positively correlated to objective environmental quality in lower-income households.

Using ‘Born in Bradford’ to dig deeper

With only weak evidence for a link between mothers’ perceptions of their local environments and breastfeeding outcomes, I decided to investigate whether more subtle physical aspects of the environment could impact breastfeeding chances using the Born in Bradford cohort study.

White British women and Pakistani-origin women showed some differences in the associations between environmental quality and breastfeeding, even though they lived in the same geographical area.

For example, water chemicals did not affect the breastfeeding chances of White British mothers, but Pakistani-origin mothers with the greatest water chlorination exposure were around 25% less likely to initiate breastfeeding and higher levels of uptake per day also increased their hazard of stopping breastfeeding by about 20%.

Women of either ethnicity exposed to greater levels of air pollution were about 20% less likely to initiate breastfeeding, but White British mothers were also at least 23% less likely to stop breastfeeding with increased air pollution exposure.

White British mothers exposed to household damp and mould were also more than one and a half times as likely to initiate breastfeeding than mothers with better household condition.

At least some of these findings contradict the idea that mothers reduce breastfeeding in poorer-quality environments. It suggests instead that mothers may be taking advantage of breastmilk’s antioxidative properties to counteract some of the detrimental health impacts associated with prenatal exposure to environmental contaminants.

Identifying behaviours from both cohort studies

There is some debate within evolutionary approaches to human behaviour about whether parental investment can be considered part of a life history strategy as the most secure evidence about fast strategies is about the timing of first birth. My final analysis therefore used data from both cohorts to situate breastfeeding within a wider suite of demographic, reproductive and health behaviours to see whether breastfeeding clusters with other traits to form identifiable life history strategies.

Mothers with lower breastfeeding chances were more likely to have got married or moved in with a partner at an earlier age and to have had their first birth earlier than those with lower rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration. They were also less likely to still be living with the child’s father, suggesting that reproductive traits do cluster together to some extent. There were however fewer consistent differences between these “fast” and “slow” mothers in other parenting, reproductive and health behaviours.

With that caveat, the faster behavioural repertoires were associated with greater socioeconomic disadvantage and environmental harshness as is predicted by life history theory, although experiencing parental death, living away from home before age 17 and exposure to air pollution significantly reduced the chances of adopting a “fast” strategy.

Overall, my research suggests that individual socioeconomic position is a stronger predictor of breastfeeding than environmental quality, but that the two are strongly linked and exert their own independent effects.

The effects of the local environment are, however, complex and depend on which indicators of environmental quality are used. Associations are not driven by individual environmental perception as much as they are by more objective measures of environmental quality. Less perceivable, more physical measures of environmental quality do not adequately explain the socioeconomic gradient in breastfeeding, suggesting that, in the UK context at least, sociocultural environmental factors are likely to have an important influence on breastfeeding outcomes. Although exact pathways and mechanisms remain unclear, intervening at the environmental level has the potential to improve breastfeeding behaviour, as well as other health and reproductive outcomes.

Read Laura’s full case study about this research.

Where next?

I will be organising a workshop on environmental impacts on health and wellbeing and will also be reaching out to environmental and infant feeding initiatives to disseminate my work further. I will also apply to present my findings at the 2020 International Society for Evolution, Medicine & Public Health Conference in Georgia, America.

Given the double or triple jeopardy some groups of mothers can experience, I am interested in exploring ideas of environmental injustice and ways in which participant-led research can empower and enable mothers to better protect their health and wellbeing and that of their children. I will be developing grant proposals to expand my research outwards a) from breastfeeding to other aspects of reproduction and maternal health and behaviour and b) to explore environmental associations with these outcomes in low- and middle-income contexts.

I am keen to conduct research in communities impacted by natural disasters and the environmental adversity brought about by the behaviour of others. I am particularly interested in working in Latin America and specifically Peru due to its high level of air pollution and vulnerability to climate change events such as the El Niño South Oscillation.

About the author

Laura J Brown is a human health and behaviour researcher, and is passionate about reducing health inequalities through research, teaching and front-line community work. She is in the final stages of completing her PhD in Demography at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, where she is a member of the Evolutionary Demography Group. Laura is also currently researching the determinants of age at first period and menopause in low and middle-income countries for a project at LSE, teaches Key Concepts in Global Health to Global Health and Social Medicine undergraduates at King’s, and provides community-based sexual health testing across London with Spectra. She has also recently tutored in Evolutionary Medicine and Public Health to Human Sciences undergraduates at Oxford, conducted fieldwork on young people’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviour regarding relationships and teen pregnancy in London secondary schools, and worked in the Behavioural Insights team at Public Health England after completing a UKRI Policy Internship Scheme there.