As part of our ongoing blog series on the 2021/2021 UK censuses, Oliver Duke-Williams and Vassilis Routsis explore changes in the census and the importance of origin-destination or flow data.

As part of our ongoing blog series on the 2021/2021 UK censuses, Oliver Duke-Williams and Vassilis Routsis explore changes in the census and the importance of origin-destination or flow data.

The 2021/2022 Censuses in the UK are the most significant in recent decades; being held during a pandemic presents significant practical problems, but also enables us – assuming good coverage – to paint our decennial portrait at an extraordinary time for the nation.

A time when many have lost jobs or been on extended furlough, when people have experienced the deaths of friends or family members, and many continue to experience long Covid-19 health problems. A time when many have studied from home, and have supported schoolchildren in studying from home, a time when many have worked online; for some a paradigm shift in the way that they work, commute, shop and spend leisure time.

It is also a time at which we have completed our departure from the European Union, a time at which we would like to know more about the numbers of UK and non-UK born workers – and yet, due to the pandemic, a time at which we our usual data sources have been affected: the International Passenger Survey was suspended for almost a year, whilst the Labour Force Survey was switched from face-to-face interviewing to telephone interviews for the first wave, and the sample size expanded in response to a drop in the achieved sample.

Changes in this census round

The 2021/2022 Censuses feature radical changes to their methodology, and the way that people completing the census will experience it.

The majority of people have completed their census form online; something that was possible in 2011, but only used by a relatively small proportion of people. People are also able to provide individual returns that modify a household level return: this may solicit different answers to some of the questions, but may also make it easier for people in shared occupation who have little knowledge of each other to provide accurate information.

Across England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, the three censuses largely feature the same question set, although they are not entirely the same.

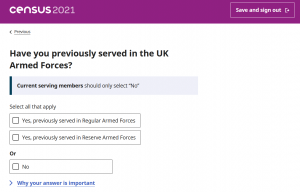

New questions ask about veteran status, about sexual orientation, and about gender identity. Some questions will be omitted (number of rooms, for example). The net effect however, is that this round will continue an upward trend of an expansion in the number of questions asked:

Number of questions asked in #census in England (an additional Q on language has been asked in Wales since 1891)#Census2021 will add three new individual Qs (sexual orientation, gender identity, armed forces veteran status) and drop a household Q (number of rooms) pic.twitter.com/7HFwJqrOWk

— Oliver Duke-Williams (@oliver_dw) August 22, 2019

Comparison of the number of questions asked over time isn’t quite as easy as it might sound – sometimes the same question may be posed as a single question with multiple tick boxes, at other times it could be framed as multiple distinct questions. In addition, there are routing points (are you over 16? If so, answer these questions…) that may or may not be counted as ‘a question’.

One of the advantages of online implementation of the census, however, is that it is possible to use previous responses to steer a person through the questionnaire, rather than asking them a routing question.

Flow data

Within UK Data Service. Oliver and Vassilis work on the origin-destination or flow data.

These are specialised data sets that are less widely known than the main aggregate observations. They are all about movement of people between places – including migration, the journey to work, and movements between primary and secondary residences.

The Covid-19 pandemic and the shift of the census in Scotland will have some important implications for these data, and we are closely involved with the census agencies in the planning of outputs.

One set of data is about changes in address: people are asked where they lived one year prior to the census, if that is different to their current address.

The data are important, as migration often has a stronger influence on local changes in population than births and deaths. NHS admin data can provide some of this detail, but with limited demographic detail.

The census allows us to explore who moves, as well as where they move between. The timing of the census in England and Wales and in Northern Ireland is suitable for helping us to understand how people have migrated; the question of where you lived one year ago is almost exactly the same as a hypothetical question ‘where did you live before the pandemic?’.

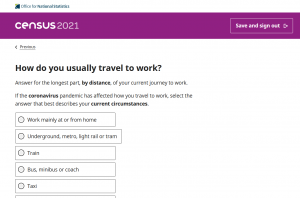

A second family of flow data are commuting flows; the census provides information here which is not collected at a national scale (and with detailed geography) by any other survey. The census includes questions about where you work, and how you get to work.

Many people are now working from home, and we will see that in the journey to work data. They will not be easy to interpret, but will offer vital insight into how people have adjusted to this process. Which occupations have more homeworkers? Are there biases in who is or is not able to work from home? For people who still travel to a workplace – have there been changes in the modes of transport that they use?

There are interactions with the migration data of course: some people may have moved house as well, with the ability to work from home offering them more flexibility in where they live. How common has this been over the past year? Is it more common in some places than others? Is it more common in some occupations that others?

The flow data can be confusing for people to work with – they take the form of large, very sparse matrices, and can have different scale geographies where flows cross borders, for example between Scotland and England.

Part of the work that we do is in creating systems to help people extract useful subsets of data for analysis, and we’re keen to get on with developing new tools to handle the 2021/22 data.

In order for those new data sets to be useful, it is of course vital that everybody completes their census.

The flow data are the largest outputs from the census, and they’ll be challenging to work with and interpret.

But, they are a crucial part of the process of understanding how the population has reacted to the pandemic in the way that they work and the places that they live; they are a crucial part of understanding how that might have changed the needs of local communities, and how we might reimagine the relationships between home and work over the coming decade.

About the authors

Vassilis Routsis is a research fellow and sessional lecturer in the Department of Information Studies at UCL, with a special interest in mixed methods research in information science. His current work at the UK Data Service is mainly focused on process and delivery of census flow data.

Oliver Duke-Williams is an Associate Professor in Digital Information Studies at the UCL Department of Information Studies, and is deputy director of the Digital Humanities masters programmes there. He is also Census Service Director at the UK Data Service, and a senior advisor in the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information and User Support (CeLSIUS).

I have a question.

Group A: There will be individuals who currently live in Scotland and will move to England post census 2021 but pre Census 2022 how will the flow during this period be counted?

Group B: The move from England post census 2021 but pre Census 2022 will have the opportunity to complete two census forms, Group A none.

How is this resolved? With estimates?

This is a summary that our Service Director for Census compiled:

For group A (Scotland to England) – they won’t be recorded on either census.

For group B (England to Scotland) – we expect them to be counted twice in the census in general.

Assuming that they didn’t also move in the year to March 2021, the won’t be in the (England and Wales) migration tables.

Assuming that they work, they’ll be included in the journey-to-work tables for England (including cases where the workplace is in Scotland).

They’ll then be counted again in the Scotland 2022 census, and would definitely be counted as a migrant (origin somewhere in England, destination somewhere in Scotland). They’d also be picked up (again) in the journey-to-work tables from a residence in Scotland.

While not entirely straightforward, we will at least be able to spot the counts of migrants.

At present we expect flow data to be published for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and a separate set for Scotland later on.

It’s unclear whether we’ll eventually get a set labelled as ‘UK’. If we do, then the workplace data will be messy. Our hypothetical person in group B will account for two flows: one from a residence in England, and one for a residence in Scotland.

How big an issue will this be? Hard to say, as it is not obvious how many people will move England->Scotland or Scotland->England. The 2011 Census recorded 41k people moving (in the year prior to the census) to Scotland from the rest of the UK, and 42.5k the other direction. If the 2021/22 flows were similar, then at least you can say that those non-counting / double-counting issues largely cancel each other.